I suspect almost every Nepali is proud of the fact — and will proudly proclaim — that Buddha was born in Nepal. But, living and working in Nepal for most of the last eleven years, I have also observed that their display of compassion and empathy for fellow Nepalis is in short supply. I am sure there are a number of different reasons behind their struggles to be empathetic or compassionate towards those who suffer and struggle in and with life even now in the twenty-first century, many immensely, as a consequence of our highly patriarchal society and casteist history, for example. I have identified four that I think are mostly responsible for that.

The first reason is the victim-blaming views and attitudes inculcated in the population by the caste system. Among other things, it teaches that the socio-economic context and circumstance within which a person is born is “deserved” (karma). In other other words, the caste system teaches people to blame the victims for their plight — any plight. Everyone is reaping the “fruits” of their past lives goes the ideology.

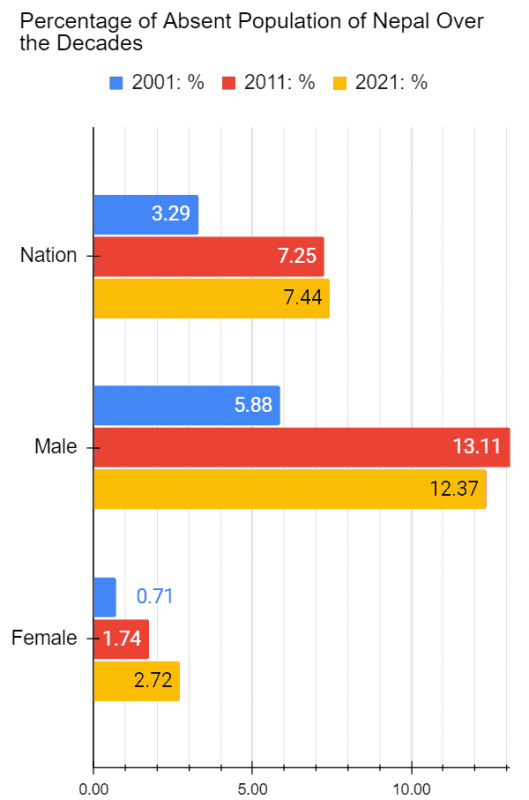

The second reason is limited travel experiences. Travel, as those who have done it extensively know, instills in the sojourner an immense appreciation for, among other things, the diversity in life, culture, and perspective etc. and values them for what they are. At any time, less than 10% of Nepalis reside abroad (see chart) but I suspect a majority of those are semi- and unskilled workers. Only an insignificant number of the population likely travel with the intention or goal of learning about and from others.

That is NOT to say that NO Nepali migrant worker learns ANYTHING from their stays in another country! But, how many have prolonged, sustained, and intimate experiences of the local culture, such as their food, their music, their dance, their festivals etc.? How many have prolonged, sustained, and meaningful interactions with the locals, and learn SUFFICIENTLY about their wishes, their dreams, their values, their lives etc.? How many create or develop intimate relationships with the locals? Work mostly consisting of labor, most of their work days are likely spent working. Their leisure time is likely spent mostly with fellow Nepalis or Indian Subcontinentals, i.e. in a social and cultural environment not significantly different from home.

To reiterate, that is NOT to say that migrant laborers don’t learn anything about the local people and culture. Many do I am sure, but for most they are likely very limited. Certainly not enough to have sufficiently deep appreciation for or understanding of — and for that to develop into a lasting and impactful relationship with — the place and people. Certainly not enough to be able to imagine sufficiently well what their life is like or what living life the way they do would feel like etc. and have empathy for all that they endure etc. (see below).

The third reason is that the quality of both formal and informal education is so poor that they don’t nurture and foster the growth of the imagination of the population sufficiently. Consequently, multiple times more are unable than are able to imagine putting themselves in the shoes of others.

Nepali formal and informal education, as far as I am concerned, actually stifles the imagination of our youngsters more than encourages or fosters or feeds it.

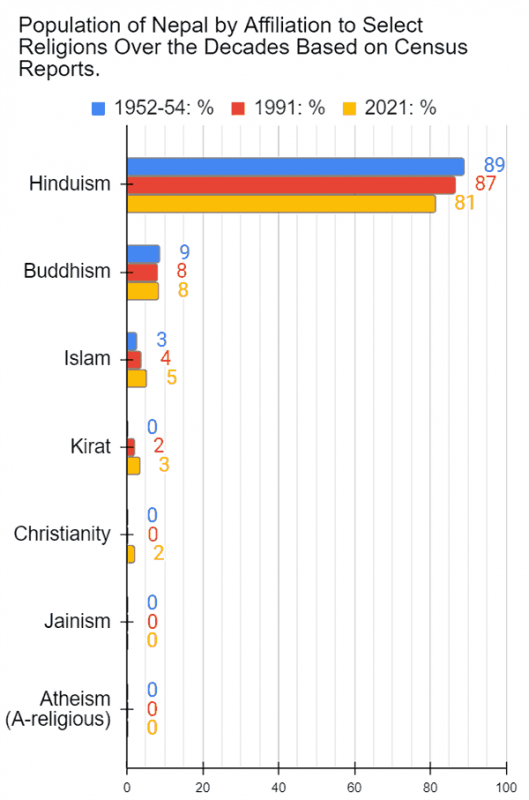

Informal education in Nepal, even today, mostly teaches students to follow many archaic and anachronistic traditional beliefs, values, and practices. One of the things it teaches the young to value and view as valuable and important, for example, is religion. Consequently, near hundred percent of the population have always been religious (see chart).

While the census data show that there is essentially no atheists and/or a-religious and/or humanists, they likely add up to a small (insignificant?) percentage. I suspect Nepalis generally are suspicious of those who do NOT follow or associate themselves with a religion and likely also believe that such people don’t have any morals or ethics when, in reality, what societies around the world show is the exact opposite.

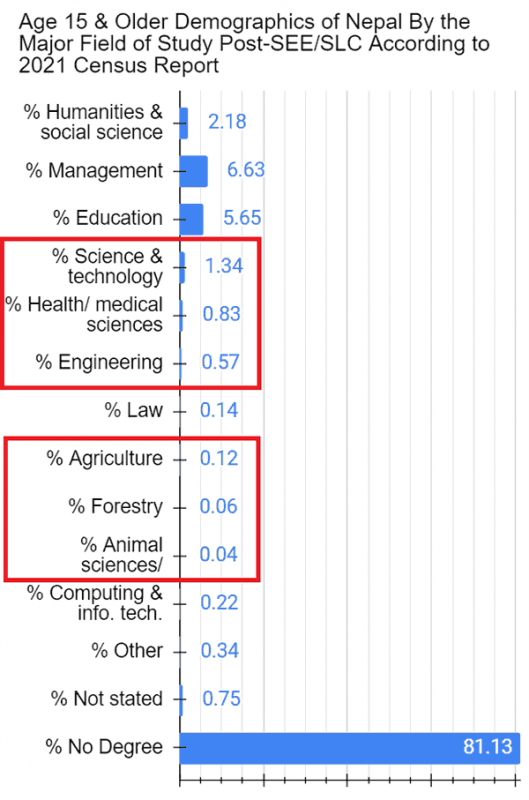

Furthermore, multiple times more Nepalis likely value religion and/or traditions more than science. After all, according to the 2021 Census Reports, less than 5% of those fifteen and older have qualifications in the sciences or related fields (those inside the red rectangles in the chart below) and over 80% have no degrees.

As such, I would NOT be surprised if there are more Nepalis who can or do quote from the Hindu scriptures about what and how things are and should be with life and the world more than from science, and even believe the knowledge and lessons in them to be of equal value in every way than science, if not of superior value.

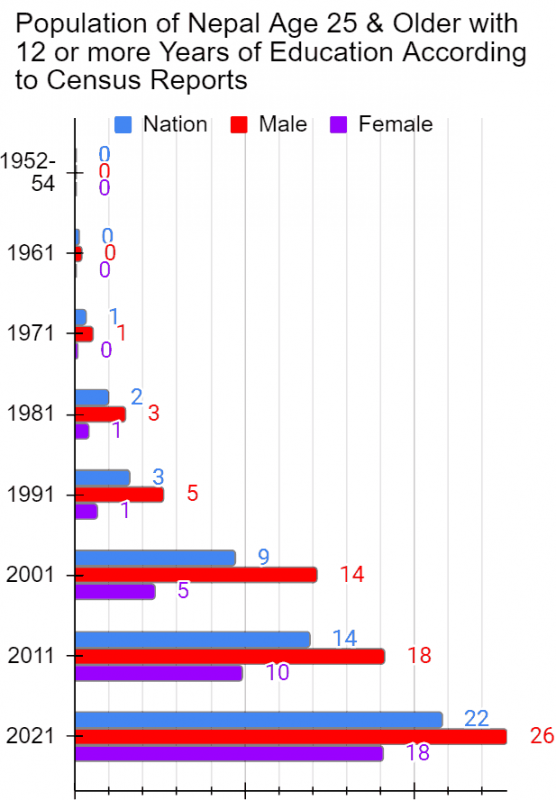

As for formal education in Nepal, not only does it not teach children sufficient science, it mostly teaches and imparts the most basic cognitive skills of recall (and some understanding), anyway. It hardly teaches students about higher level thinking skills. What’s more, the level of education of the population having mostly this abysmal quality of education has always been unacceptably low (see chart below).

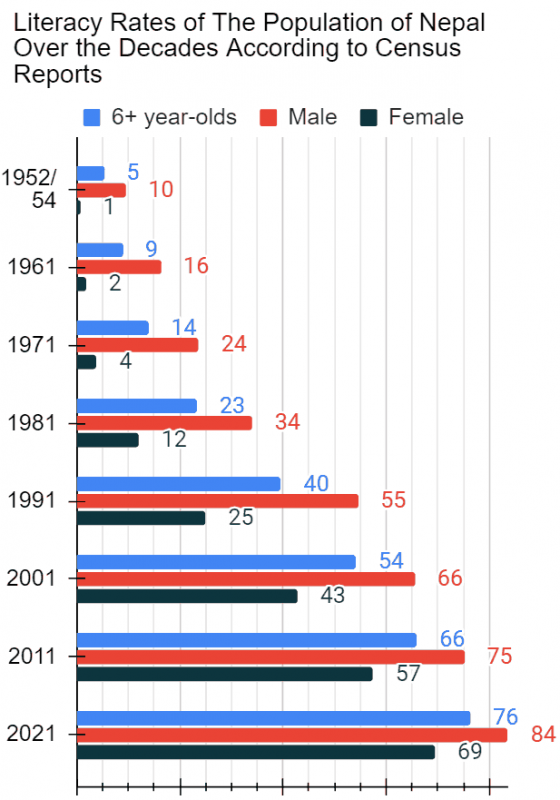

In fact, in the century of probes on Mars, Virtual Reality, and Artificial Intelligence, we don’t even have 100% literacy, and at the rate we have been going over the last seven decades, it’ll be at least two more decades before we do (see chart below)!

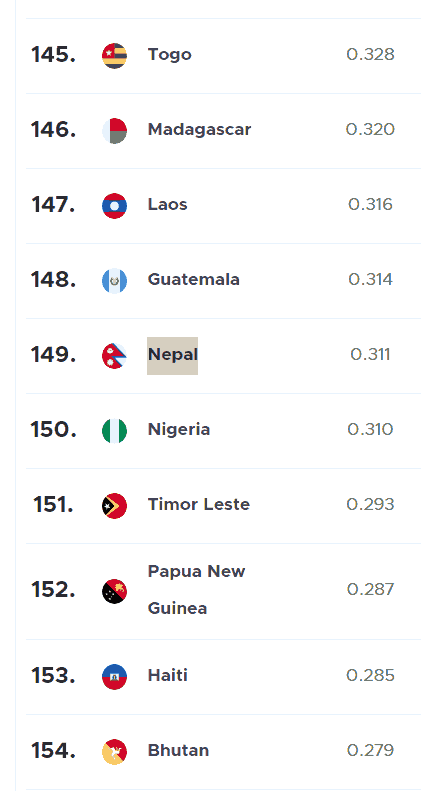

In fact, the education system in Nepal is so poor that we are ranked 149th out of 177 countries. That is, we are in the bottom 25%.

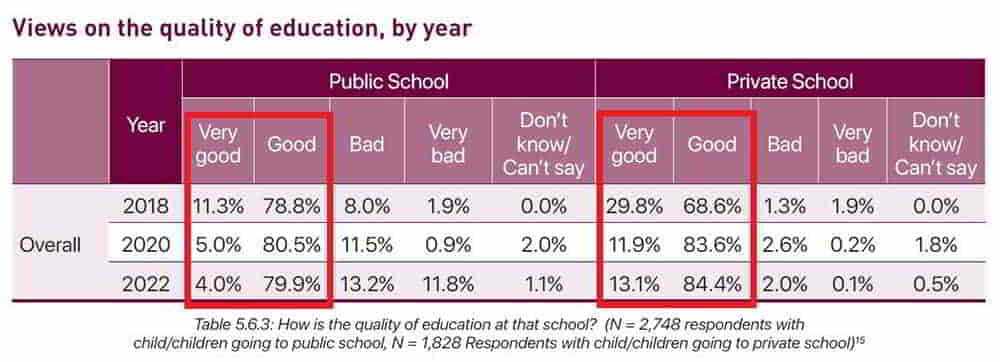

The quality of education in the country is so poor, an Asia Foundation survey discovered that a vast majority of the population don’t even know that it’s poor; they actually think that its “Good” or “”Very Good.”

One of the many consequences of that is that what they can’t imagine saying or doing or experiencing, generally Nepalis assume other people NOT saying or NOT doing or others NOT experiencing.

The fourth and the final reason is tied to both education and imagination. Nepalis education culture — whether informal at home or formal in school — does NOT stress or promote reading.

According to the 2019 Multiple Indicator Survey results, only 3% of children under the age of five have three or more children’s books at home. According to the same survey, only 6% of children between the ages of seven and fourteen have three or more books to read at home. BUT curiously, the same survey reports that 93.9% of those children “read books or are read to at home.” My feeling is that that was a mistake, likely resulting from an issue in the wording of the question or from a misinterpretation of the question or from something else because, as you likely have already realized, that does NOT follow. My own guess is that that the 93.9% include children reading their school textbooks, not just those reading for leisure.

Were reading prioritized, encouraged, and instilled in children as do societies where education is valued, that would have, among other things, fed their imagination. Additionally, one of the many other benefits of reading for leisure that studies have shown is the fact that people who read, whether children or adults, on average are more compassionate and empathetic than those who don’t.

So…what sorts of things do I think Nepalis struggle to imagine apart from those I have already stated? Here is a list.

- imagining others BELIEVING (in) and PRACTICING things that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves believing or practicing

- imagining others THINKING about (themselves, life, the world, the universe etc.) & in ways that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves thinking

- imagining others DOING or WANTING things that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves doing or wanting

- imagining others FEELING in ways that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves feeling

- imagining others HAVING or FACING or ENDURING life experiences that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves having or facing or enduring

- imagining others SEEKING/PURSUING things and life experiences that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves seeking

- imagining others SUFFERING from issues that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves suffering from

- imagining others INTERPRETING things in ways that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves interpreting

- imagining others HAVING an understanding of life and the world that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves having

- imagining others ENDORSING/EMBRACING systems or way of life or way of thinking they that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves endorsing or embracing

- imagining others VIEWING and/or LIVING life in ways that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves viewing/living

- imagining others VIEWING the world in ways that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves viewing

- imagining others VALUING things/ideas/principles etc. that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves valuing

- imagining others BEING a certain way, or BEING a certain kind of a human being, etc. that they aren’t or can’t imagine they themselves being

- Imagining others QUESTIONING that which they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves questioning

- imaging others having INTELLECTUAL INTEGRITY that they don’t have or can’t imagine they themselves having

- imagining others FIGHTING for things/ideas/causes/principles that they don’t or can’t imagine they themselves fighting for

- imagining others being considerably more BROAD- and OPEN-MINDED, accommodating, tolerant etc. than they think they themselves are etc.

On the contrary, Nepalis generally project a lot, view and interpret things and what someone else is doing or saying mostly from their own perspective or where they stand. They are highly judgmental and, in the process, miss out a lot (see image below)!

Once again, the above are all my own observation or conclusion and NOT based on any scientific study or sound survey and so have their limitations. But, my sense is that were someone to formulate a set of questions for a survey — or to design a study — investigating the ability of Nepalis to empathize and/or their imaginative powers, my observations will likely be borne out. Of course, it goes without saying, surveys and investigations of those kinds also have their own limitations.

Regardless, given all that about Nepalis, will a time ever come when a MAJORITY of them recognize that not just all Nepalis but all of us living beings, including the animals, share a destiny and if we are to ensure our survival, empathy for and compassion towards others is crucial?

Having said all that, I MUST end with a disclaimer for the benefit of fellow Nepalis. The arguments I made above, of course, do NOT apply to ALL Nepalis. That is, in every argument I make above you must add, “Not all Nepalis”. Yes, obvious and redundant to most but I have learned from experience that it’s not…not to many Nepalis!

What do you think?

(This blog post was produced with materials from a Twitter thread published on June 16, 2022 and a Facebook post made on Aug. 15, 2022.)

Spot on, Dorje. Sharing widely.

Dear Shirley,

Thank you! Much appreciated.