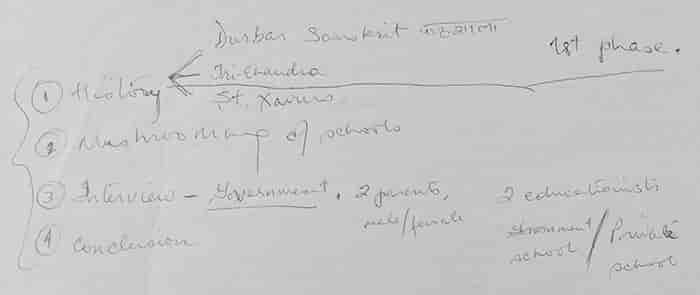

Written some time in 1997-98, what follows appears to be some observations about education in Kathmandu. At the time, I had returned to Nepal for a longish stay before going back to university for my teaching certificate. I came across the write-up some time ago but decided to publish it now. It appears to be written in preparation for something much bigger (see image above), but what? I can’t tell nor do I recall. However, part of what appears in this I did use in one of the episodes of the hour-long Kantipur FM music program I used to host. Regardless, enjoy!

* * * * * * * *

Educational Institutions and the Ridiculous

Even as late as the beginning of the fifties [I was writing this in the last 1990s], there were scarcely any educational institutions to speak of. The end of the Rana rule paved the way for the State’s march into modernism. An essential element of modern Nepal was gong to be education. Starting with only one or two schools in the fifties. the numbers increased slowly at a snail’s pace until the nineties when it exploded! The march then had taken a form of a 100-meter dash run.

For the longest time, until the numbers shot up like a rocket out of control, the names of educational institutions were generally very much local, indigenous, Nepali that is. There arc many words in Nepali for “school” such as bidhyalaya or bidhyapith or bidhyashram or bidhya mandhir. As there were three levels of schooling, three kinds of schools could be found: Primary, Lower-secondary, and Secondary school. A school therefore would be designated either a prathamik or ninmna-madhyamik or madhyamik school. So, the whole name of a school would consist generally of the name, level taught, if just one, followed by the Nepali term for school. The designation “High School” was also used by some.

One of the first schools in the Valley of Kathmandu is called Durbar High School. Some other well established schools are Adharsha Bidhya Mandhir, Anandakuti Bidhyapith, Sarswati Prathamık Bidhyalaya and Sidhartha Vanasthalı Madhyamik Bidhalaya. All very much Nepali.

And then came the ridiculous: pre-school, kindergarten level education, and what was called higher secondary school education. Don’t get me wrong, their introduction in and of themselves was not what, to me, was ridiculous. What is ridiculous is the excess– unnecessary–baggage that came with them.

First the baggage that came with kindergarten level education. It started with the obsession with the so-called “Boarding School” as opposed to the regular day-schools. The other one was the none Nepali names. Many of these pre-primary schools labeled themselves “Boarding School” or “English Medium School” or some combination of the two, setting the trend for appending them to the name of the school.

A perception appears to have been generated and instilled by and on both the education institutions and the society that education at a “Boarding School” or an “English Medium School” was better than at regular–even well established–day schools. One of the basis for such perception appear to be the apparent higher degree of competency in English the students acquired at boarding schools. And then for the parents there were the extra perks which went with sending their kids to such schools: social recognition and respectability! The kind of school one sent one’s kids little by little appear to have become a status symbol.

Apart from the new categories, English names that were unabashedly cute appear to also have gained currency, such as Little Steps, Little Angels, Little Tots, Seseme Street, Seseme World, Mary Paupins, Wendy House, Mickey International etc. Adding fuel to the increasingly status-conscious and growing population of middle and high class Kathmanduites, names that very much sounded foreign–read “English”–appeared to have joined the competition, such as North Point, West Point, Stanford, St. Lawrence etc.

Next, the extra baggage that came with the introduction of Higher Secondary School (HSS) level education, the alternative to what until then had been known as Intermediate Level, a two-year post secondary education before on continued on for one’s advanced education. Until the early nineties most of the Intermediate Level campuses (as they are known) were government (public) institutions. Their names were, again, simply local, such as Amrit Science College, Tri Chandra College. Shankar Dev Campus etc. The introduction of HSS also fed the Kathmandu residents hungry for status symbols by setting yet another trend in the naming of academic institutions.

Categories from International School, International English Boarding School, Academy, Co-educational Residential School, to the outrageously ridiculous Alternative to American School appears to have been added to the vernacular of institution names.

So, in a short span, school names had moved from the local to cute English ones (Little Angels) to imports–either already well known in the field of education (North Point), or that which hinted of North American popular culture (Seseme World) etc.–to names that meant nothing in the context of Nepal and didn’t mean what they said they were, such as Stanford International School (which I doubt is an international school), Xavier Academy, Holy Vision College etc. I guess Sarswati Madhyamik Biddhyalaya, in these times of “progress and development,” has no currency in the midst of the likes of Don Bosco College, St. Lawrence etc. in the metropolis of Kathmandu. Never mind that some of the parents might not even be able to pronounce such names! My parents certainly couldn’t pronounce St. Xavier’s properly!

What’s sad and pathetic is that a discerning person can immediately pinpoint, on the basis of all these changes, the direction the Nepali education system is heading in — namely, not a direction that merits serious consideration. The direction therefore must be changed because these are trivial and mere cosmetic changes. As far as I can tell, what takes place inside the classrooms of most schools–whether it be Adarsha Bidhya Mandhir or Little Angels College or Stanford International–is mainly teaching not educating: teaching of facts and figures by the teachers to the students; teaching of facts and figures for the students to rote learn and regurgitate in the exams, basically parroting and not much of anything else. Educating is much more than that, of course. It involves, amongst other things, the active process of imparting skills–such as analytical and problem solving skills–necessary for a successful professional and personal life. Education is about fostering, in the student, the ability to think, the ability to think independently and critically.

* * * * * * * *

So, the write-up ends there. What was it ultimately meant to be? What was it for? I wonder.