Locating, restoring and recompiling my digital records and documents, following crashes of two of my external hard disks, I have come across many documents that I hadn’t viewed in a long time. Among them are the papers I wrote for different classes as an undergraduate student at Grinnell College in the United States of America between 1990 and 1994. I have decided to reproduce some of them here in my personal blog.

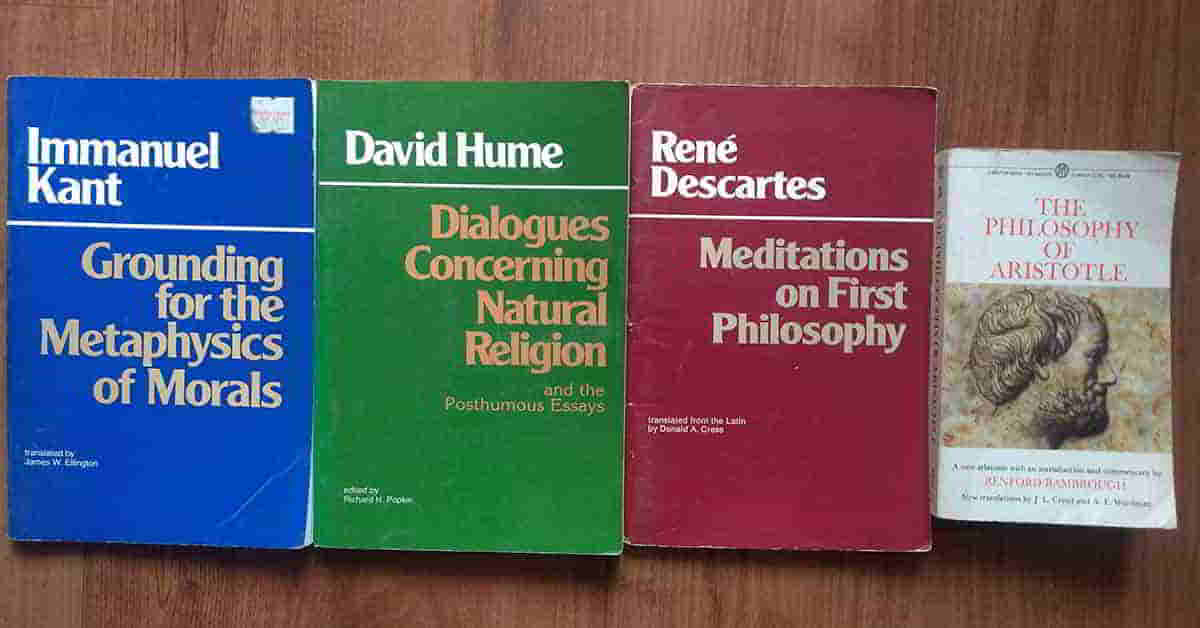

This is one of the papers I wrote for my Introduction to Philosophy class. In it, I compare and contrast the opinions of two philosophers.

* * * * * * * *

On The Existence of God

Does God exist? There have been as many philosophers who affirm to this question as who do not. Rene Descartes is one such philosopher who has painstakingly tried to show His existence. David Hume, on the other hand is of the opinion that we simply cannot know. What are the evidences that each presents that purport to their beliefs? What are their bases for their differing opinions? In attempting to answer these questions, first, their aforementioned views on the subject will be elaborated. Having done that, their primary philosophy will be explicated and the link between it and their view on this particular subject made clear.

Descartes establishes firmly that God exists. He draws upon three proofs that necessitates it. First and foremost he brings to notice that, the very fact that a thinking being, namely himself ( or any human being ), has an idea of a God within himself, stipulates the very existence of Him. His second proof is drawn from the proof of causality: God is the ultimate cause. The third proof deals with the fact that since we as human beings cannot sustain ourselves in time, it must be something else that must be responsible for keeping us alive from day to day. And that something else is God.

Having established that a thinking being exists–“I think, therefore I exist”–he goes on to the establishment of methodological indubitability of whatever is found to be existing and true by extension from that first principle. Methodological indubitability, Descartes ascertains, grounds his conclusions he would ultimately come to. The manner in which he goes about proving the existence of God is likened to proving a geometry theorem.

He first sets the basis for building his proof by establishing the existence of the being that thinks. The proof is built up in such a manner that it contains no element of doubt which would pull down the whole thing. Whatever he concludes through his method then becomes necessarily indubitable. Thus, his belief in the existence of God is tied in closely to the fact that a thinking being exists.

Consider the idea of God that the thinking being has. Firstly, he cannot deny that he has that idea because he is aware that he has it. The idea cannot be a false one because if it were false then the idea would have proceeded from nothing ( that is, it would represent nothing). But the thinking being does know what it represents. He is aware of all the attributes of God–that of his being eternal, infinite and perfect etc. Hence God must of necessity exist.

Secondly, there must be a cause for the idea of God that is within the thinking being. The idea could not have originated from the thinking being because that would make God of the thinking being himself. The thinking being knows that to be false. He knows his own limitations, is aware that he does not have all the qualities characteristic of God. The idea was not drawn from sensory perceptions. So the cause of the idea has to be more perfect and must have all the qualities the idea purports it has. The idea of a more perfect being than himself, the thinking being, that has been caused in him must have proceeded from a being more perfect than himself then. That must be God.

Thirdly, the thinking being is aware of the fact that he does not sustain himself. He depends on something else for survival and is aware of his own drawbacks. He knows he is not perfect so he doubts and desires and is aware that he doesn’t have the power to continue his existence of himself a little later. These observations point towards the existence of a being other than himself that must be responsible for his being kept existing. That other being that must necessarily exist must be God.

Hume is uncomfortable with the notion of existence of God and the proofs that have been offered. He finds fault with both the a priori argument (the causal proof or the necessary existence argument) and the a posteriori argument (the design argument). He holds that we cannot know whether God exists or not. That is something not provable. There is no way one can get any concrete evidence on the nature of God.

The fact that no argument posited to account for the existence of God can be demonstrated, makes all arguments invalid. One can conceive of God being non-existent as well as existent. Neither does the fact that a thing can be conceived of as existent prove its existence nor does the fact that it can be conceived of as non-existent prove its non-existence. There is no necessary existence that can be attributed to God, or to anything that is claimed to exist for that matter, since both conceiving of as existing and not existing can be carried out by the mind. This does not imply any contradiction. Hence existence of God cannot be proven.

Descartes is a rationalist. His philosophy is based entirely on reason. For whatever he established, all that was required was to establish one truth and through reasoning establish something else. Because the establishment of the existence of the thinking being necessitates by reason the existence of another being then the other being (God) must also exist.

His causal theory can also be a reason to think that it necessitated the conclusion of God existing. A cause being something that brings about an effect, it has to have enough or greater degree of reality to it than the effect which it brings about. Hence, from this the reason to think that something that come to exist must necessarily have a cause that is more perfect and contains more reality than the effect. That is the relation between God and the thinking mind.

Hume on the other is an empiricist. All knowledge for him is based on experience. It is only through experience, or lack there of that the mind can actually conclude or not conclude anything. Experience leads to custom or habit formation of the mind. Custom or habit in turn induces the mind to believe in something. For instance, after having watched a ball left in mid-air fall down many times the mind believes that the ball will fall downward if left in the mid-air again. But there is no necessary connection between the ball left in mid-air and falling to the ground. There is nothing, no process, no reason to ascertain that leaving the ball in mid-air necessitates its falling down. It is through just a conviction that future will resemble the past. The mind could as easily imagine the ball going upward forever. There is no logical inconsistency in that. There is no reason whatsoever for the mind to think that it must fall downward and not go upward.

Unlike Descartes, he has perceptions divided into two: first, impressions which are lively and vivid; second, thoughts and ideas which are less lively and less vivid. Ideas thus are merely imitations of impressions. The various ideas have connections between themselves. The connections can be of three types which are: resemblance, contiguity and cause and effect. Of the things that can be known, they can be put into two categories: those that are relation of ideas and those that are matter of fact. The mind can be made always to take the relation of ideas to be certain because of the fact that they can be demonstrated to be so. This kind of knowledge is that of mathematics. Matter of fact on the other hand are knowledge of cause and effect gotten through experience and not through any kind of reasoning. In other words, the relation of cause and effect in and of themselves belong to matter of facts. The contrary of matters of fact could well be true because the contrary can be conceived of without contradiction. The same mind can conceive of the contrary (let’s say of existence of God) through the same faculty as if it were conforming to reality. And it could for all the mind knows. There is no experience that he can revert back to refute it. In this manner the cause and effect Descartes talked about is different from Hume’s.