The “brilliance” of the insidious caste system, to me, is what Ambedkar calls its inherent “graded inequality.”

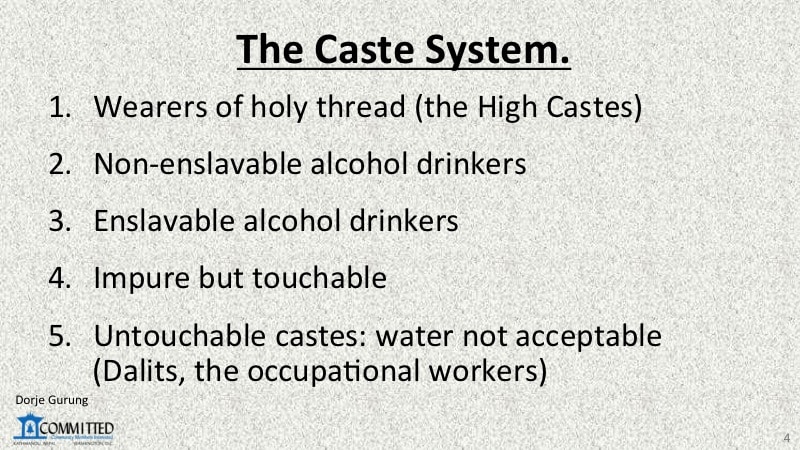

The five castes (see image), the five social groups, are graded top to bottom.

Social ranking also exists within the groups that make up a caste. That is, stratification exists between the groups that make up each social group — in the case of all but the High Castes, the ethnic groups. The gradation does NOT end there.

There is stratification within pretty much every ethnic group. Pretty much every ethnic group is made of a number of different communities of people. There’s a hierarchy to the way the communities are structured. And guess what? There’s gradation even within every community of people! How brilliant is that?! That intricate stratified structure essentially functions as a check on people’s ability to object to, challenge or question, and overturn the excesses of the caste system.

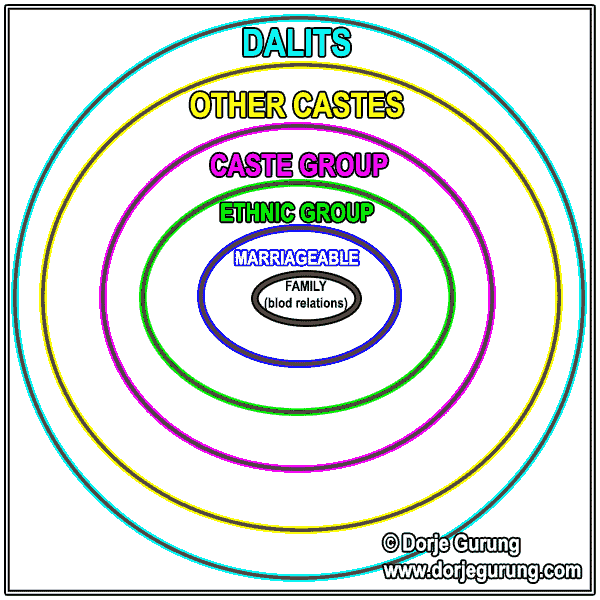

In part I of this series, I outlined how Nepali society is made up of a caste-dictated structures. For an individual, it’s made up of concentric circles of people with his/her family — the most important structure — occupying the central position (see image below). People move within bubbles defined by and related to it.

In this follow up blog post, I go into the details of how the intricate gradations dictates a crucial activity: family alliances, i.e. marrigeability, to show how they also control communities and individuals.

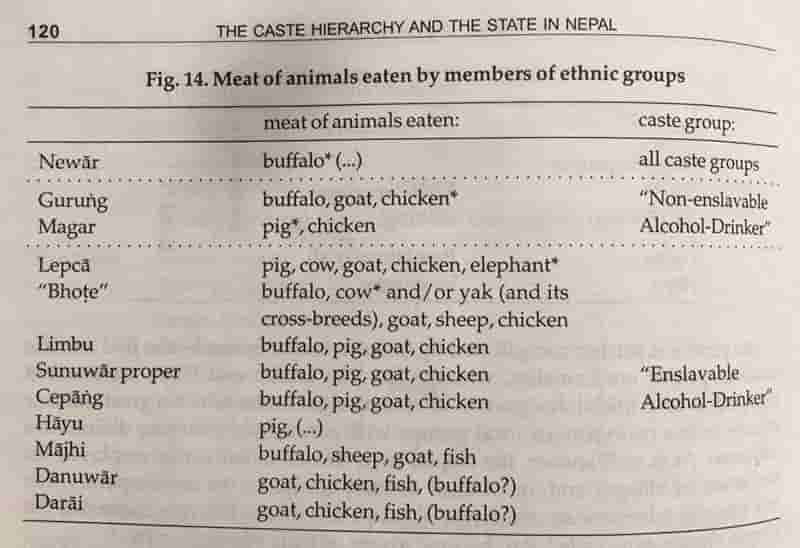

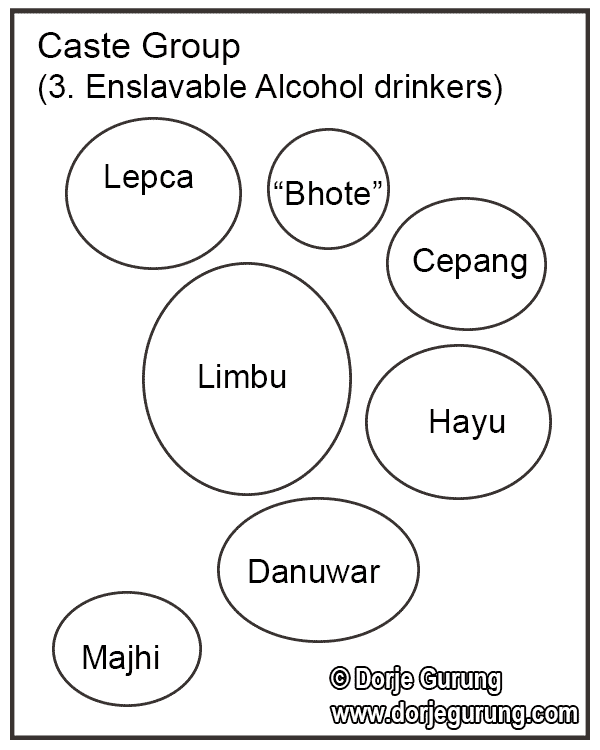

As was alluded to earlier, apart from the so-called High Castes, the Khas-aryas, other castes are made up of different ethnic groups (see image below for an example). The image, for instance, lists a number of the ethnic groups belonging to the third caste, the Enslavable Alcohol-Drinker caste.

According to the 2011 Census Report, the population of Nepal is made up of 126 caste/ethnic groups! I am pretty sure — while not very clearly stated or delineated or spelled out anywhere by anyone and/or likely not even understood very well by many — the gradation exists between as well as within ALL the 126 ethnic groups.

To begin with, the high castes (“wearers of the holy thread”) are divided into Bahuns (Brahmins) and Chettris, the former being of higher status. Among the three named ethnic groups (in the image above) belonging to the “Non-enslavable Alchol-Drinker” castes — Newar, Gurung, and Magar — Newars likely see themselves as being of higher status than the other two. I could be mistaken but, within the “Enslavable Alcohol-Drinker” caste, Limbus likely see themselves as of higher status than the rest. Furthermore, members belonging to pretty much every one of the rest of the seven named ethnic groups could likely describe the status of their own ethnicity relative to the rest. What’s the likelihood of all of them being consistent however? I don’t know but I wouldn’t put my money on it!

As for within Bahuns, the highest caste, the Upadhayay, for example, occupy the top spot! I wouldn’t be surprised if the different communities of Chettris are graded too. As for the communities that make up ethnic groups, the Newars for instance, have their own “high castes” (such as the Shresthas, the Pradhans etc.) and “untouchables” (such as the Shahis). The Gurungs too have their own sub-categories: the “Char jat” and “Solah jat” (the four and sixteen clans respectively). The latter are of lower status. (Incidentally, I am NOT a Gurung, contrary to what my surname says.) The gradation, as has already been hinted at, does NOT end there…of course! That would be too straight-forward!

The gradation within an ethnic group, of course, partly dictates who you can — rather really should — marry.

That is, who one can create a familial alliance with and in that way, indirectly, serves as a hindrance to establishing alliances with or showing allegiance to or getting too “cosy” or “friendly” with just anyone in general. Of course, naturally, some from different ethnicities or castes do find themselves getting close but end up up suffering as their relationship is unacceptable to one or both families.

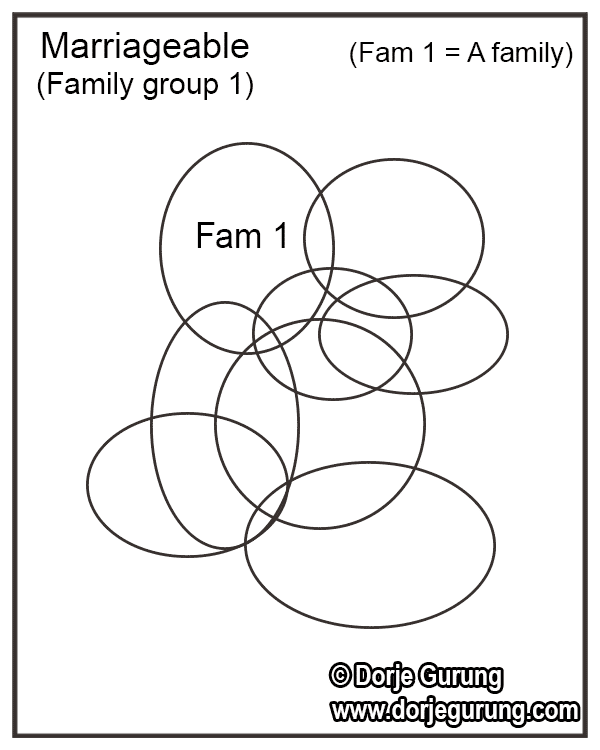

Let’s look at the communities of Shresthas and Shahis belonging to the Newar ethnicity. In the diagram below, let’s assume Family 1 represents a high caste Shrestha family.

All four families overlapping with them, our Shrestha family here could potentially establish a familial alliance with through marriage. All four and the rest would likely belong to the same social status. The reason they might NOT be able to establish a familial alliance with the others may be for some other reason, such as patrilineage. Of course, only eight families are shown just for illustration. But the important thing to note is that ALL eight families would belong to Shrestha and/or of similar “high status/caste” Newar communities.

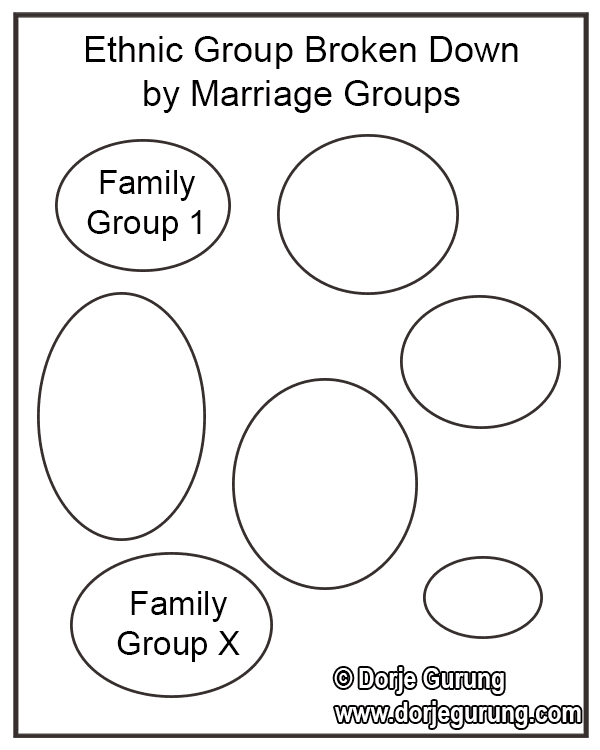

Next, let’s have a look at the diagram below which shows an ethnic group broken down by marriage group families. In other words, those within a circle represent a group of families that are connected to one another through marriage and/or their ability to potentially inter-marry. Of course, again, only seven are shown for illustration.

Returning to our Shrestha family (belonging to family group 1)…. They would likely bulk at arranging the marriage of a son or daughter of theirs with one belonging to a Shahi family, who, because of the latter’s lower status, belong to a complete different family group, say X in the image. Similarly, within Gurungs, the likelihood of a Ghale Gurung’s family, “char jat” Gurung, being amenable to one of theirs marrying with or into one belonging to a “Solah jat” Gurung would likely be low or even zero.

What’s amazing about the graded inequality in the caste system is that it’s found even within my people of Upper Mustang, who are all Tibetan-Buddhists and ethnic-Tibetan (Bhote in Nepali and belonging to the third caste)!

Those at the top of the pecking order are members belonging to the royal family, who go by the surname of “Bista,” a surname denoting a Chettri. The Tangbetanis, my community, originally from the village of Tangbe, are one of the lower status people among the Mustangis. Patriarchs of families from other villages, for instance, have likely never or rarely visited the homes of Tangbetani carrying a bottle of their best home-made brew, or vise-versa! (During the course of the visit, when the host drinks the brew the guest serves, the deal is sealed!)

And of course, within the community of Tangbetanis, while there are those one cannot obviously marry because of, again, patrilineage, there are also those one SHOULDN’T marry because of their lower status within the community or can’t hope to marry because they come from a higher status family! In other words, even the small community of Tangbetanis, families can be broken up into marriageability groups (“Marriage groups” in the above image). I would be very surprised if this were NOT the feature of most other communities belonging to other ethnic groups as well.

When i was a child, I remember being instructed to NOT do — and not doing — many of the things with one uncle and his family (including his children, my first cousins) that I was able to do with the rest of my uncles, aunts, and first cousins. I discovered the reason only as a young adult: his wife came from a family of lower status from ours! In the eyes of this uncle’s siblings and relatives, he had lost his “higher status” and therefore he and his family needed to be treated like an “unequal.”

What all of that also boils down to is that two randomly picked Nepalis will likely be able to tell where their taha (“social place”) is relative to the other based on the combination of their facial features and/or their names and/or their surnames.

Members of families belonging to different Family Groups following the practice of not inter-marrying generation after generation is now the Nepalis’ Sanskiriti or Chalan (tradition) and therefore must be followed, so goes the argument anyway!

Sure, for a long time, many Nepalis from different ethnic groups didn’t even come in close, regular, and sustained contact with one another because of the geography of the country and lack of infrastructure. But, even now, social interactions between them is more limited than one would expect. Even in urban centers, social gathering are significantly more exclusive than they appear to a casual observer and also more exclusive than what many might believe them to be.

Here are two tweets I made to a hill so-called high caste Hindu man restating that truism.

What are d chances of our social worlds over-lapping in a significant manner?

Nearly zero!

Anyway, to reiterate, Nepalis are FORCED to—& do—live in completely different worlds&realities based pretty entirely on their #caste—even those w/ exactly d same educational background…+— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) December 1, 2020

Contributing to that is the lack of knowledge and understanding about one another. All a legacy of of generations of conscious and deliberate social segregation and poor education. Nepali education — both formal and informal — insufficiently educates the population about fellow Nepalis, among other things. That naturally leads to at the very least distrust of and at the worst fear of others. We humans fear that which one doesn’t know enough about or one does NOT understand, or that which is very different from ourselves.

The result? Nepalis being pretty closed and inward-looking as a people in general. As a matter of fact, when Nepalis talk about “us” and “them” the “them” generally refers to those beyond the third concentric circle. That’s a lot of “them”!

So, what has ended up happening is something I pointed out in the first of the blog posts in this series:

Self-segregation driven by expectations and pressure from the society and reinforced by members of the two inner circles help maintain the above division.

Consequently, the high status members within an ethnic group (Shresthas within Newars, for example, or Ghales within Gurungs, or Bistas within Upper Mustangis), by “necessity” (i.e. social standing), “segregate” themselves even from many others of their own ethnic group.

Those in the middle also “self-segregate” from those farther down in the hierarchy to maintain their “middle status,” as it were. The most “inferior,” those at the bottom, have little choice but to limit themselves to their own kind because those “above” them won’t accommodate them.

To conclude, a large majority of Nepalis, whether high, middle, low, or some other in-between status, socialize and work and, therefore, spend a large chunk of their time with members within the three inner circles.

And that extends to between ethnic groups within a caste (see image below) and of course also between castes as well. Having said all that, in some instances, the reason for self-segregation is as much just based on the perception of one another by the members themselves and mutual history as on anything else.

Given the strong familial and social expectations to “self-segregate,” which ultimately ends up facilitating their marriage to someone from one’s marriage family group, how many will defy the overt and covert pressures and, instead, marry outside?

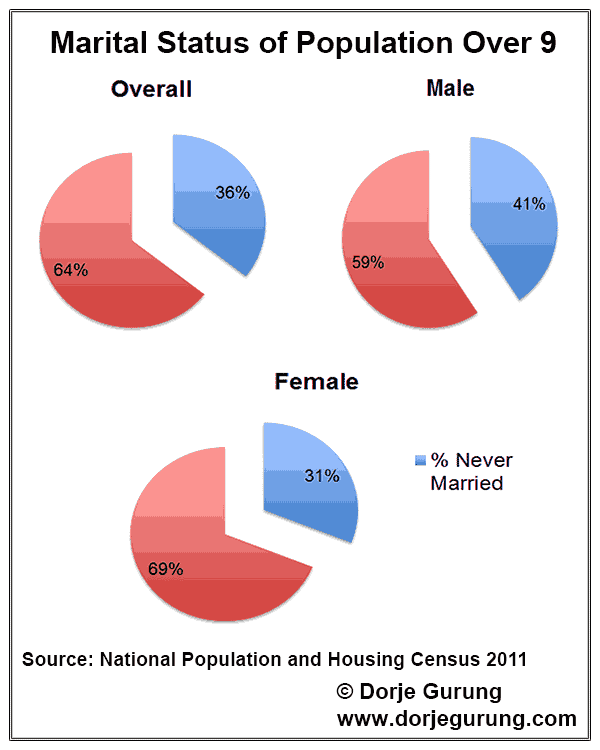

According to the 2011 census report, 64% of the population either had married at one time or another and/or were still married (see chart below).

A vast majority were likely arranged marriage between couples from the same or similar social status. What percentage would have involved an arranged marriage between a couple from vastly different social status, whether from a community or an ethnic group or from different ethnic groups belonging to the same caste? Likely zero. What percentage would have been arranged inter-caste nuptials? Again, likely zero. What percentage would have been inter-caste “love marriage”? Likely a small or insignificant percentage.

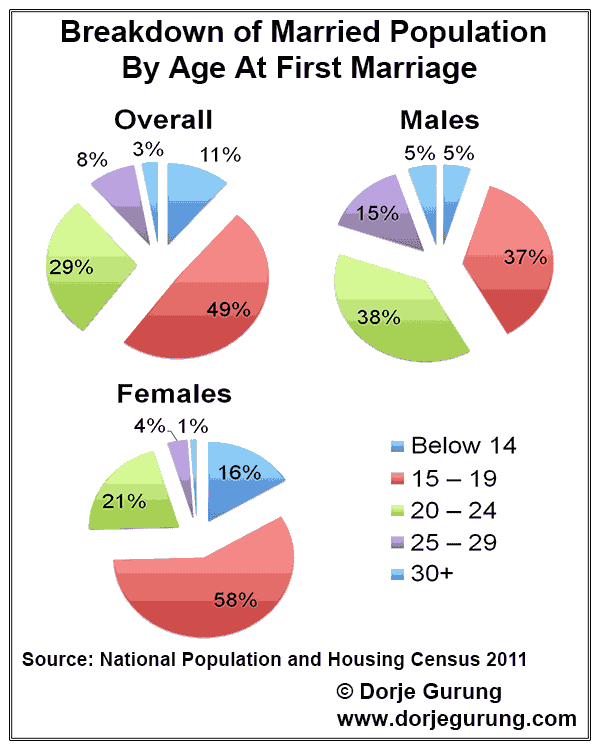

The reason? See below for pie charts breaking down the married population of the country by the age they were when they got married for the first time.

A whopping 80% of males and 95% of females had been less than 25! Given that Nepali youngsters in Nepal START getting any degree of independence from their families ONLY into their twenties, and a vast majority of them will have developed very close ties with mostly of those from within the first three concentric circles, a vast majority of the couples very likely had arranged marriage, ARRANGED by their families. Additionally, they must have come from families of the same or similar social status.

What would be the consequence of marrying outside your family group? You would pay a price for that. To begin with, many families do put their children — even adult children — through mental and emotional agony over marriage. It’s not unheard of for families to disown their own children for refusing to marry someone the family found for them or for marrying someone they didn’t approve of. It’s not unheard of for couples from vastly different social status to elope and get married on their own for fear of their families preventing them from tying the knot. One reason Nepali families marry off their children at such young ages, especially girls, is out of a fear of their child eloping and bringing shame on the family! About 3 out of 4 females, for example, had still been teenagers when they were married (off)!

Marrying and living within relatively small bubbles and valuing those within those bubbles more than others has some dire consequences for the society, which will be the topic of follow up blog posts.

So, what are the chances that Nepalis will accept inter-caste marriage as normal, as they do the sun rising from the East every morning, and when? The reason that’s important is that, again, I agree with Ambedkhar when he declared that the only thing that will dismantle the caste system is inter-caste marriage.

What do you think?

References

Added after the publication of the blog post because of their relevance.

Bennett, Lynn, Dilli Ram Dahal and Pav Govindasamy, 2008. Caste, Ethnic and Regional Identity in Nepal: Further Analysis of the 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, Maryland,

USA: Macro International Inc. [Added Jan. 17, 2021.]

SetoPati (July 16, 2021). ३५ सय वर्षको जातपातको इतिहास (भिडिओ र रिपोर्टाज) Excellent interview with Aahuti about the history of the Caste System in Nepal going as far back as 3.5K years!! [Added on July 19, 2021.]

Hello,

1. You cannot compare Newar and its hierarchy with other Janajati ethnic groups and their hierarchy. Newars’ hierarchy is based off of Hindu varnashram from Rajopadhyaya Brahmins to Kshatriya Chathariya (Malla, Pradhan, Amatya, Joshi, Shrestha, etc.) to Vaishya (Tamrakar, Tuladhar, Kanskar, Halwai, Panchthariya etc.) to Shudras (Maharjan, Dangol, etc to all the artisan castes like Prajapati, Manandhar, Chitrakar, Balami, Ranjitkar, Karanjit, Nakami, etc.) to the ‘untouchables’ (Kasai/Shahi, Kulu, Jogi, Dhobi, Pode, Chyame, etc.) Newar caste strucuture is much more elaborate and urban than that of the Khas/Parbate (which instead of calling it this you continue to divide on their caste lines as higher caste and Dalits). In fact Newars, Khas, and Madhesis are the only three ethnicities of Nepal that have a social structure based on Hindu varna model.

2. The social divisions of all other groups of Nepal is not based on Hindu principles (whether they are not influenced by it is another matter), but rather based on their own ancient tribal or clan system that is natural for every tribe or clan. So for these Janajati ethnicities (Magar, Gurung, Tamang, Limbu, Rai, Sherpa, and Tharu, Danuwar, Majhi, etc.), their idea of high-low was not based on Hindu ideals of pollution and purity, hence they did not traditionally have Brahmin priests nor untouchable castes. I think you need to make yourself clear on this basic fundamental concept first as to why comparison between a Newar Shrestha and Shahi is not actually same as comparing a Gurung 4 jaat and 16 jaat,

3. In the Muluki Ain, Newars were placed in 4 of the 5 divisions, so no Newars are not just an Un-enslavable Alcohol Drinking group like you have consistently but wrongly described. Newar Brahmins (Rajopadhyayas) and Kshatriya (Chathariya Shresthas) were placed among the Tagadhari group of Janeu wearers, a good chunk was placed in the aforementioned Un-enslavable Alcohol Drinking group (Pachthariya Shresthas/Bare-Gubhaju.Uray and Jyapus and other smaller service castes), where as a few other Newar castes like Shahi (Kasai), Dhobi, Kapali, Sangat were placed in the 4th category of water touchable but impure group where as three Newar castes (Kulu, Pode, Chyamaha) were placed in the absolute bottom on the hierarchy, below Parbate/Khas service castes in the category of impure and untouchable.

Dear DM Shrestha,

To begin with, thank you for taking the time to comment. I do appreciate it.

To respond to it…in the first point you make, I am Not sure I understand what you mean by “1. You cannot compare Newar and its hierarchy with other Janajati ethnic groups and their hierarchy.” All I did was point out/use the fact that there is stratification/grading WITHIN every ethnic group too (in addition to grading between the five castes) including within Newars, Gurungs, and Mustangis.

The second point you make starts off saying with “2. The social divisions of all other groups of Nepal is not based on Hindu principles (whether they are not influenced by it is another matter), but rather based on their own ancient tribal or clan system that is natural for every tribe or clan.” Yes, you are right. I don’t think I have indicated that the gradation found between or within ethnicities are ENTIRELY based on the Manusmriti. If that’s how it comes across then the mistake it mine.

Another point you make there is “I think you need to make yourself clear on this basic fundamental concept first as to why comparison between a Newar Shrestha and Shahi is not actually same as comparing a Gurung 4 jaat and 16 jaat.” I have NOT made any COMPARISON between Newars and Gurung apart from to STATE that there is hierarchy within Newars, and there is hierarchy within Gurungs, that they both have groups that have “high caste”/high status members and “low caste”/low status members.

As for the third point you make, yes I am sure, as you say, there are variations within Newars. That some are even placed in the same position as the hill so-called high caste Hindus, while others are lumped with the Dalits. I don’t dispute that. But all of that would be beyond the scope of this blog post which is only trying to delineate, in general, how there is stratification WITHIN ethnic groups. As for Newars being placed in the Un-enslavable Alchohol Drinking group, sure, again SOME newars might not be or maybe even should not be placed in this caste group. Again a discussion of that would be way beyond the scope of this blog. But the point I make here stands that within Newars, there is stratification, whether Newar as a group is classed under one caste or two or three different of the five castes.

I hope that helps clarify some of your objections!

Once again, thank you for your comment.

Thank you for your insightful response sir,

A correction, the line “The social divisions of all other groups of Nepal is NOW* based on Hindu principles (whether they are not influenced by it is another matter)…”

Having said this, I completely agree with you on the point that there is internal hierarchies among Newars as with other groups. But what I was trying to point out is that the dimension of hierarchy and social stratification of the 3 caste-following ethnicities of Nepal (Newar, Khas/Parbatey and Madhesi) with the non-caste following ethnicities (Janajatis) of Nepal is fundamentally different. Yes, hierarchy is there in both these caste and non-caste groups, but former is varnashram based and is inherently part of the larger Indic-Arya civilizations whereas the latter is not.

While your point of stratification within these both groups through your examples is very clear, my point was that a more nuanced understanding and difference between caste and tribe is needed to further understand Nepal’s social hierarchies. Just for an example, although both look and seem similar, we cannot get a true picture if we make a comparison American blacks and South Asian dalits because the history and complexities and outlook between the two groups while on the surface level may seem similar, is vastly differing.

Similarly, in the Shrestha/Shahi and 4/16 jaat Gurung case, the scope and dimension is very different. (And I illustrate this point with no intention of ill will but purely for academic argument based on our society’s past) A Shrestha will not marry Shahi because of the very Manusmriti based notions of caste/varna where a Shrestha thinks the Shahi is ritually unclean, the touch of that person will defile the Shrestha and will require purification. Shrestha thinks of himself as a Hindu-Kshatriya of his society and the overarching role as a patron caste and expects to be treated by others as one, and sees the Shahi as a outcaste Shudra. Caste endogamy (marriage) as well as food and diet rules govern how he treats the Shahi. He will not step inside the house of the Shahi and in the old days, caste segregation meant the Shahi had to build his house outside the city limits and use different water taps. No matter how poor a Shrestha is, his mind will always have a sense of superiority over a rich Shahi. This is based on the notions of caste and varna and on the holy Hindu books, most prominently of the Upanishads.

All this is not there within the 4-jaat and 16 jaat Gurung. The rules of difference is rather based off of clan or tribal differences or myths that propagated over the centuries that made 4-jaat superior over the other. Rules of purity and pollution, caste and heredity based professions, untouchability, etc. are not there. As with many other societies of Arabia or China or Europe, such a society stems from ruler-serf traditions where 4-jaat were probably the ruling/powerful clans who overtime dominated other groups and developed the sense of superiority.

That is why a more nuanced, more appropriate comparison between caste groups would be between parallel groups within groups. So a Newar Shrestha/Shahi comparison is appropriate when compared with Chhetri/Damai or even more aptly with Madheshi Rajput/Kalwar groups. To understand notions of caste, Hill Brahmins could be comparable with Terai or Newar Brahmins and not with entire caste societies like ‘Madhesi’ or ‘Newar’ or non-caste societies like Magar or Gurung as often done by even respected social scientist. What has happened instead is the Parbate/Khas society is so fragmented now that the collective identity of being Khas is obsolete, replaced by the individual caste identities within that ethnicity (Bahun, Chhetri, Kami, Damai, etc.) forming into their own ethnicities. So now, people mistakenly compare castes within Newars as similar to differences within Bahun (Upadhyaya, Jaishi) where as it should have been between Newars and Khas. Likewise among the non-caste Janajati groups, 4 jaat/16 jaat Gurung would be aptly compared to 12 and 18 Tamangs, or the Rana Tharu/Athpariya Tharu divide and the 7 main clans of Magars.

Dear DM Shrestha,

Again, to begin with, thank you for your long and considered comment. I truly do appreciate it and I don’t mean that sarcastically. I agree with pretty much every single major point you make! Plus, you have increased my storehouse of knowledge about Nepali society and our hierarchical social systems. The only thing is that to dwell on them in this blog post would have been irrelevant, given the point I am trying to make.

I couldn’t agree with you more when you said, and I quote, “But what I was trying to point out is that the dimension of hierarchy and social stratification of the 3 caste-following ethnicities of Nepal (Newar, Khas/Parbatey and Madhesi) with the non-caste following ethnicities (Janajatis) of Nepal is fundamentally different.” Absolutely.

However, to dwell on that too would be way beyond the scope and point of this blog post, making it considerably long, to begin with. (As a matter of fact, the MAIN topic is so vast that this is only the second one in the series! There will be more follow-up posts on the topic. While this one covered marriage, follow-ups will cover the severe lack of collaboration for example.) The point of this blog post is to argue how the hierarchies within an ethnic group (whatever the reason or explanation for the hierarchies themselves are) prevent arranged marriages between families from different communities but belonging to the same ethnic group.

You also pointed out, and I quote: “While your point of stratification within these both groups through your examples is very clear, my point was that a more nuanced understanding and difference between caste and tribe is needed to further understand Nepal’s social hierarchies.” Absolutely! Again, I couldn’t agree with you more! Nuanced understanding is ABSOLUTELY needed! But again, because of the topic of this blog, dwelling on that would be tangential…though, again, important, very important!

Again, a point you make that I agree with wholeheartedly: “That is why a more nuanced, more appropriate comparison between caste groups would be between parallel groups within groups.” Such a treatment would elucidate more and educate a reader more on our social systems…but beyond the scope of this blog post, which is about why there is hardly any inter-caste arranged marriage, or even arranged marriages between members belonging to the same ethnic groups but come from different communities.

What I have realized is that the blog does NOT make clear the fact that the stratification WITHIN an ethnic group are NOT based on the Manusmriti, something you pointed out in your first comment. Believing that to NOT be relevant or crucial to the understanding of the argument I make in the blog, I removed a concluding sentence spelling that out, which had been part of even one of the last drafts. Here it is: “Having said all that, as an IMPORTANT aside, I would like to point out that I am NOT arguing that Nepalis in the above examples NOT crossing ethnic and/or caste boundaries is ENTIRELY because of beliefs about hierarchy or informed by hierarchy based on the Hindu concepts of caste, derived from the Manusmriti.” Now, in light of your comments, I am realizing keeping that sentence might have been helpful!

Once again, thank you for taking time to comment and enlightening me! Much appreciated!

Thank you for your response and please don’t think of my response as a criticism of your post, I just wanted to add that one bit which I thought was worthy of a mention. You are indeed right, there are lot of things to be understood and not everything can be fit in a blog post! Plus not everything can be understood and studied all at once. But as it is, this blog is very insightful and deserves to be seen by more Nepali people to understand the social complexities of our nation. Immense thanks to you for trying to clarify!