It’s NOT just that the education system in Nepal is, by all accounts, the most corrupt system in the country. It’s NOT just that it’s so pathetically and horrendously of poor quality that it fails to meet the academic needs of a majority of the children of the country.

Nepali education system actually sets students up for failure by putting them through a wringer.

Having ensured their failure, when they do fail, they blame them for it, and, to round it off, makes them pay for failing — the rest of their lives. Forget educating them in a way that, for example, makes them life-long learners, independent and critical thinkers, and in some way prepares them for life, or for the world, or in a way that puts them on a path to realizing their human potential etc.

The past several months, no different from many other countries around the world, Nepal has been suffering from the coronavirus pandemic. While many countries around the world cancelled examinations, the board for grades 11 and 12 in Nepal didn’t. The original examination dates (in May) were cancelled as the country was under lockdown. In October, six months later, it announced that the examination would indeed be held starting on November 24.

As if the added stress of having to prepare — since May — for an examination at an unspecified time during a pandemic hadn’t been bad enough, it was supposed to be the first one using the new format: the 30-marks-per-paper format! The students saw the papers for the first time during the examination.

Of course, studies have shown a relationship between emotional and mental well being and academic performance, both in general and under examination conditions. It possible that, likely being products themselves of our poor quality of education, the Board doesn’t know that. Worse, they might know but do NOT care about the emotional well-being AND the academic performance of the students. (On a side note, of course, the consequences of the poor quality and level of education of the population during these times of the coronavirus pandemic are not being borne just by students such as them. The entire country is.)

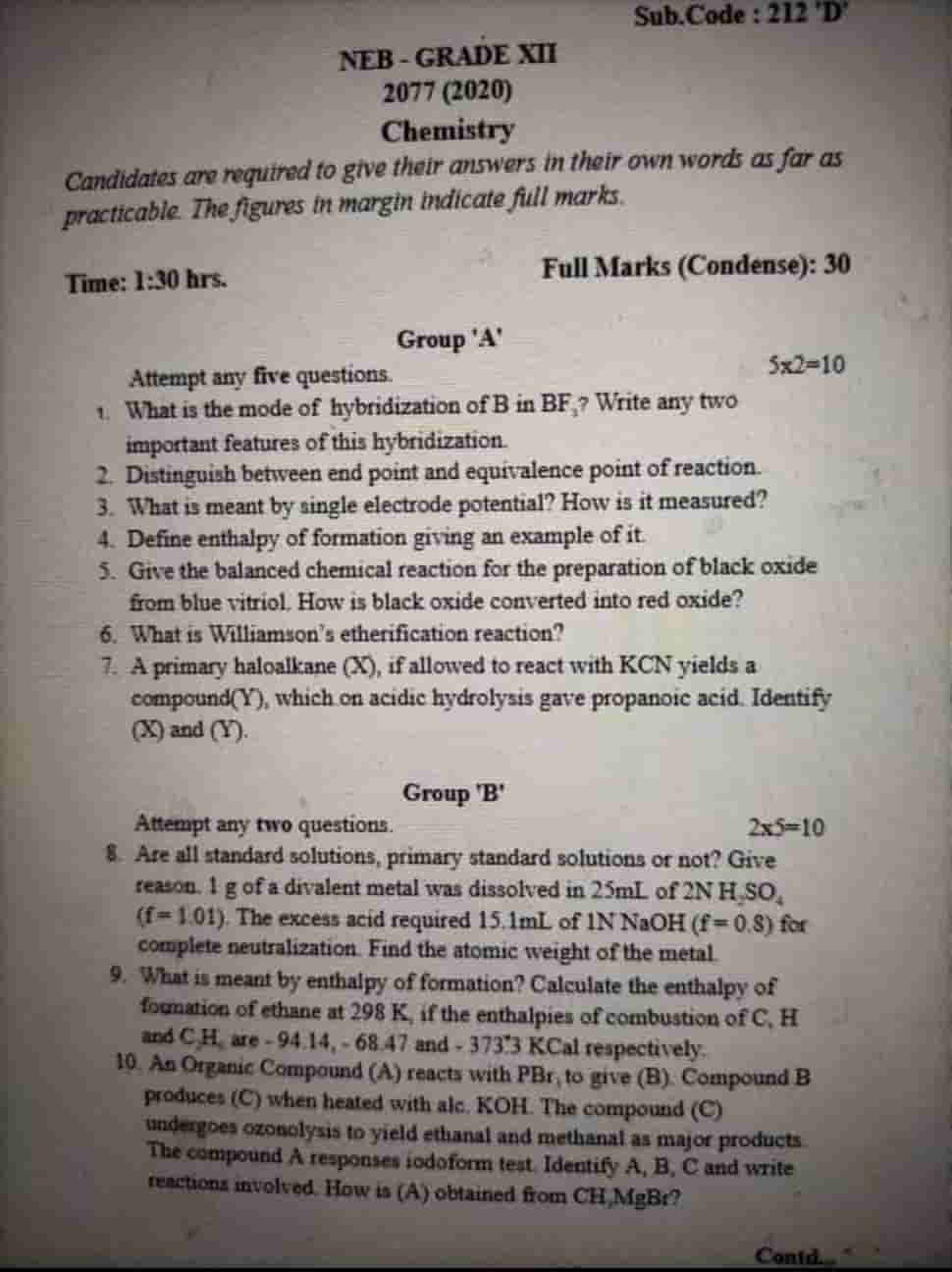

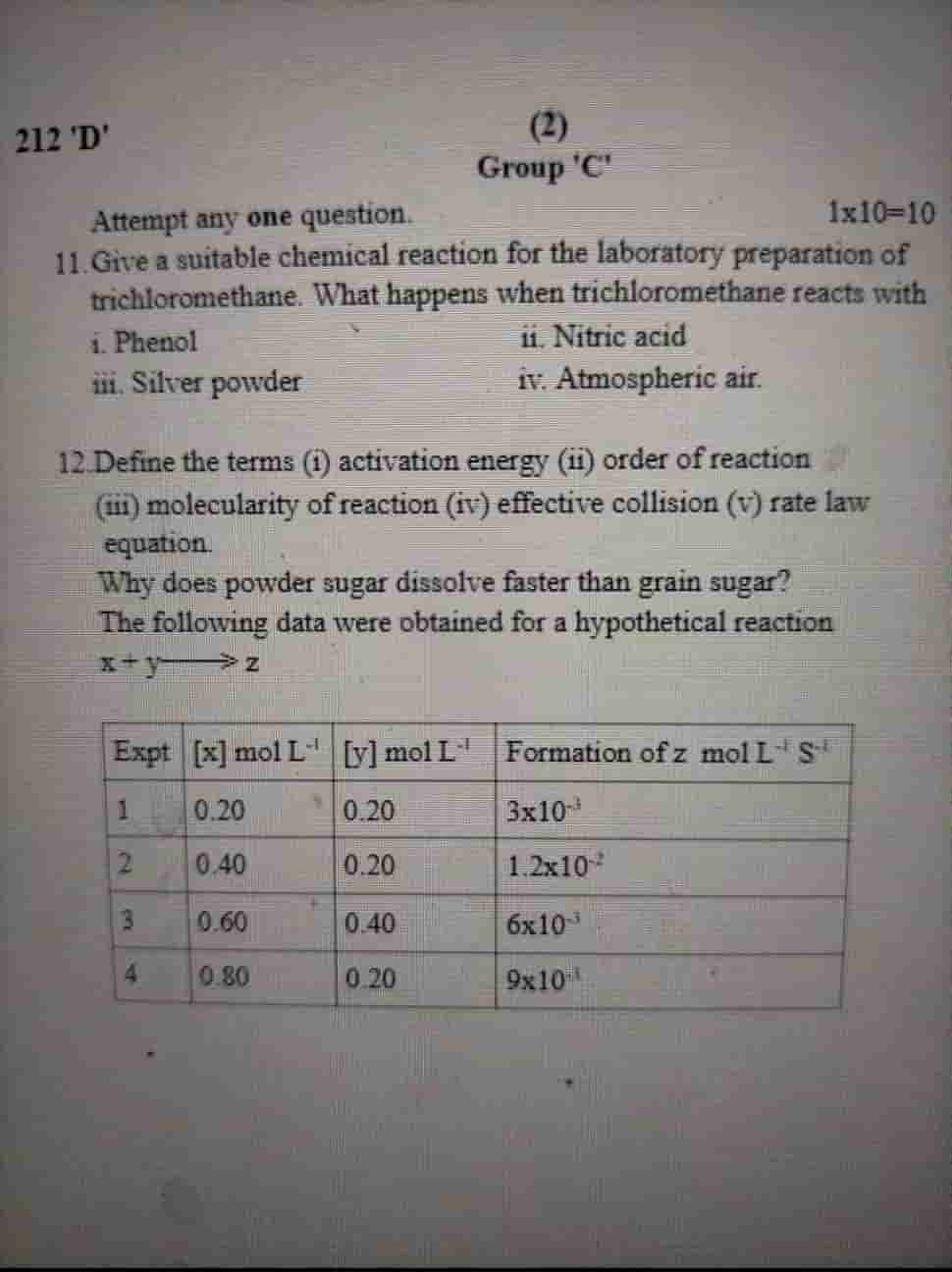

All that notwithstanding, what of the examination papers themselves? I came across — on Twitter — what looked like the Chemistry paper. Going through it, I found many issues!

The bottom line? The examination is NOT about education and assessment, in the true sense of those words.

In this first blog post on the subject, I shall be evaluating and commenting on the paper as a whole and what they indicate about our education system. In the follow up blog post, I shall shred the contents to bits!

Here is the paper.

To begin with, the English — the language — is pretty embarrassing and makes you cringe in a number of places!

The instructions say “candidates are required to give their answers in their own words as far as practicable.” That’s NOT what is expected though. The expectations generally in pretty much all examinations Nepali students take is regurgitation of answer they have committed to memory. This examination is NO different.

Next, if “1:30 hours” means 1.5 hrs and it’s worth only 30 marks, that’s already a major issue for a few different reasons.

What I means is, if indeed it IS 1.5 hrs long — that is, a majority of students would take that long to complete the paper — AND if the maximum marks they could get for their efforts is indeed ONLY 30 marks, then there’s something MAJORLY wrong with the questions in the test paper and/or mark allocations.

Conversely, if indeed there’s nothing wrong with the questions and mark allocations, and it’s TRULY worth only 30 marks, then the time allotted for it is WAY too long.

The other issue is the fact that the examinees have to answer 8 questions, every single one of which consist of two or more parts. That’s too many questions for a paper worth only 30 marks. There should have been fewer questions. Or if the paper was required to have 8 question, then it should have been worth more. (Analyzing the question, I discovered that the paper is indeed worth more than 30 marks, but that will be the subject of the follow up blog.)

Where am I coming from with those arguments about timing, mark allocation, and questions?

Well, during my years of teaching grades 7-12 science internationally, we had a standard practice when creating and administering test papers. We allotted 1.5 mins per mark!

The logic is that each mark is for a single idea or concept or A point, which takes about that much time to conjure up and express.

A 1.5 hr examination paper, therefore, would have been worth 60 marks. Conversely, a 30-mark paper would have been allotted only 45 minutes. In other words, there was a logic to the duration of the examination and/or the worth of the paper based on the assumption that a student is able to identify and/or respond with an idea or concept within 1.5 minutes on average. No such logic appears to have guided the examiner of this examination paper.

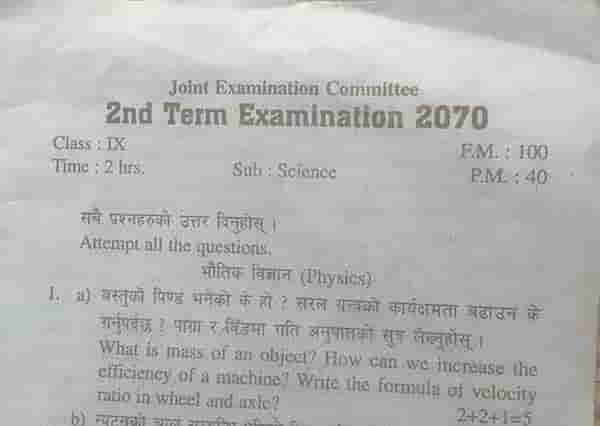

In case you are tempted to believe that this may be an aberration, here’s a grade 9 science test paper (see image below).

Once again, if indeed this is a two-hour long test paper, that is, one that most students would need two hours to complete, it should be worth less than 100 marks. If on the other hands, the questions in the paper are such that they are really worth 100 marks, then it should have been allotted more than two hours, more like 2.5 hours.

Having said that, a two-hour test or examination is too long for fifteen-year olds!

To me, all of that shows how little the board care about important details such as those.

As far as I can tell, they don’t appear to have been guided by any guideline, process of thought, reason, or logic. They don’t care about them, just as they don’t appear to care about the mental state of the students when they dillydallied with the dates for the examination. An examination, might I remind you, that followed a new format in the examination papers, sample papers for which the students has not seen at all. I would love to be proven wrong however.

Next, the paper is divided into three groups, A, B, and C and within every group, they have choices! As far as I can tell, the justification for the grouping, if there is one, is not at all clear from the questions.

Questions within a group are NOT QUALITATIVELY different from those in the other two groups. That is, there are no differences in the kind of the questions nor are there any differences in the complexity of the questions. The only difference is that they are worth different marks, which alone does NOT warrant them being in different groups, of course.

That they have choices within every group is also an issue. That tells me that the syllabus does not include foundational knowledge, understanding, and skills all the students are expected to master during the course of the year-long study. Had they, there would have been at least a few compulsory questions assessing their level of mastery of them.

There you go! From the board not taking into consideration the extenuating circumstances of the pandemic to cancel the examinations to some general issues with a chemistry examination paper. In the follow-up blog post, I shall be going through the test paper question by question and show you how the paper indeed has some major flaws and also how they point at other issues, such as with the syllabus.

But then again, only a board that produces this kind of a examination paper would display the lack of care and concern for the emotional well-being of the students they are supposed to be serving during these stressful and unprecedented times of the coronavirus pandemic. Only such a board would show an apparent lack of knowledge and understanding about the relationship between emotional and mental well-being and academic performance. Only such a board would instead make the student suffer through it all and hugely impact their academic and personal lives that follow.

Do they know that stress weakens the immune system and that’s exactly the opposite of what you want happening to your body during a pandemic? Probably not. Or, if they do, they don’t care.

What do you think?

(If interested in a blog post about issues with language Nepali education, with Nepanglish click here. If interested in an analysis of practice questions in a grade 11-12 guide book, click here. In interested in a blog post about how Nepali education system teaches children to NOT think, click here. If interested in one of the ways Nepali college students made to memorize stock questions and their answers, click here. Click here for a video of the way young Nepali students memorize questions and their answers and how primary school students “study.”)