The Spring of 2019, I was running workshops for teachers at a public school in Kathmandu. In one of the sessions I touched on some of the negative impacts of using corporal punishments. Following the workshop, a teacher shared his story to demonstrate to me why, as far as he was concerned, it is necessary.

He had started his teaching career at a private boarding (residential) school. There, he had been violent with the students all the time apparently because that had been part of the school culture.

But, interestingly, at some point he had come to realize that the students may possibly not be learning and performing as well because they feared him! Fear, he had discovered was the most predominant feeling the students had when they were in his presence. So he changed! Little by little he abandoned his violent ways. And, not surprisingly, his students’ achievements improved quite significantly!

But then, after some years, he had left that job and come to work at the current public school, where too corporal punishment was the norm. That forced him to go back to his old ways.

“Here,” he concludes by way of explanation, “if I don’t punish them physically, they won’t respect me.”

Of course, the realization that the learning outcomes of the students was secondary to their apparent respect for him even if just out of fear, was something I had a hard time wrapping my head around.

Having said that, when we were students in the seventies and eighties, teachers (and parents) were expected and — under many circumstance — even required to use violence with children…and did.

But, that was long before violence against students was made illegal — in 2005. Until then our laws permitted it both at schools and in homes. As far as I am aware, it is still allowed in homes.

The change in the legal statute, as far as I can tell and NOT surprisingly, does not appear to have brought about significant changes in the school culture still.

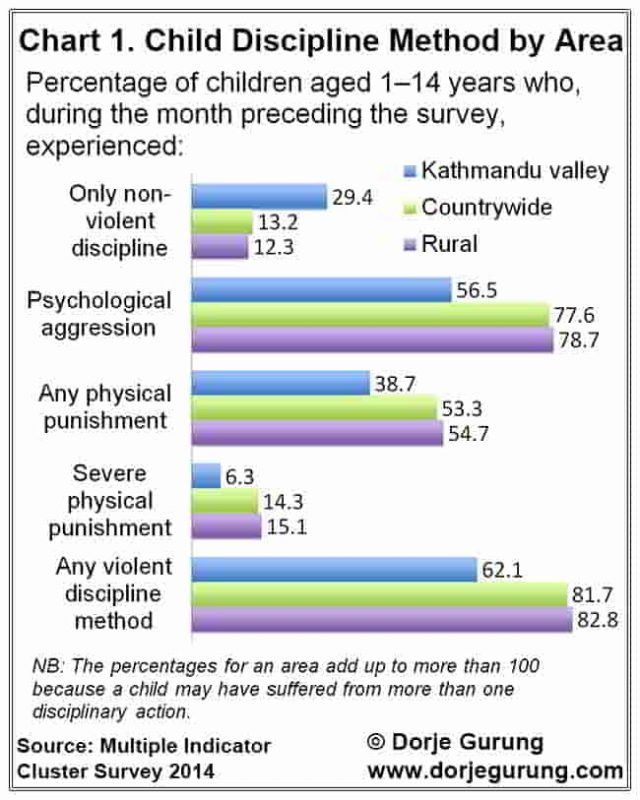

A 2006 survey of Nepali students found that over 80% of them had suffered from physical violence in the hands of their educators. A seven-district Plan Nepal study in 2011 showed 39.34% of students had suffered the same in the hand of teachers. The study also showed that the reason behind 5.34% of dropouts quitting had been corporal punishments.

According to Tarak Dhital in 2013, General Secretary of Child Workers in Nepal Concerned Centre, a children’s rights organization, “The majority of schools in Kathmandu employ teachers who resort to corporal punishment.”

The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2014 discovered that over 80% of children interviewed had suffered from physical violence in the hands of their care-givers at home the month preceding the interview! (“Any violent discipline method” in the image below.)

One reason behind the lack of success of the law is the lack of awareness about it. The other is lack of implementation. Those two, of course, must also go hand-in-hand with the introduction of the new provision in the legal statutes for it to be effective.There’s also another reason behind the changes in legal statute not making a significant dent in the practice of corporal punishments in school. Namely that, violence against children is deeply rooted in our culture.

We in Nepal have our own equivalent of “Spare the rod, spoil the child.” Found in the Hindu epic Ramayana, it goes something like this: “भय बिनु प्रिति नहोई” (Bhaya binu priti nahoi). It translates into something along the lines of “Without fear there is no love/affection.”

When it comes to educating and raising children, one of the interpretations of that is love and affection for children when educating them should be accompanied with fear of punishment. Furthermore, the cultural belief is that the punishments should, among other things, instill also a fear for teachers, administrators, parents, in general adults.

That in turn teaches them to respect adults and authority figures. And, once they grow up to be adults, the assumption is that they will automatically accord respect to older adults and authority figures out of fear of punitive action.

Another reason for instilling fear-based respect is our highly stratified society. That practice — fear induced by power differential, whether it be about children respecting adults, females respecting males, or about those in lower positions respecting those in higher positions in an office or organization, or about those of lower castes respecting higher castes etc. — props up the highly stratified social as well as other structures, such as organizational, and reinforces them. The fear arises from the real potential for the person with more power demonstrating or displaying that power violently — verbally, emotionally, or physically — and they do too. We are a pretty violent society.

We have a whole saying which describes that practice, that process: “Taha lagaunu” (“To put someone in their place”).

We don’t have a dearth of adults in Nepal who believe in all that.

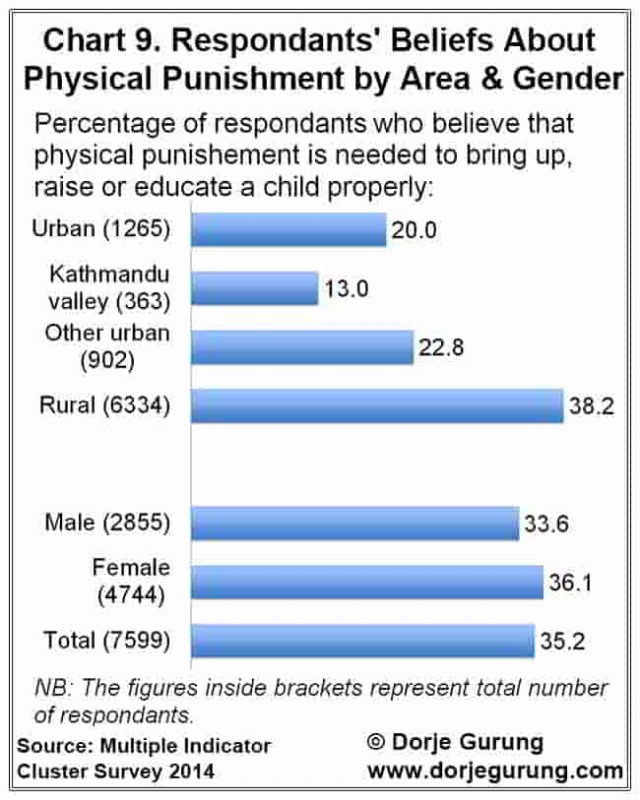

MICS2014 also discovered that 35.2% of the respondents believe physical punishments is necessary to raise and educate children (see image below).

In other words, a significant percentage of people in Nepal feel instilling a sense of respect for adults and those in positions of authority through fear is necessary and likely believe in its efficacy.

This June 26, 2019 article is about three teen aged girls at a private school being seriously injured when their science teacher beat the crap out of them. The article reports the Principal Sadhana Bhujel as contending that

निजी विद्यालयमा विद्यार्थीको हितकै लागि डरत्रास देखाउनु सामान्य भए पनि पछिल्लो घटनामा शिक्षकको चरम गल्ती भएको…। (While it’s normal at private schools to incite fear and apprehension in students for their own good, in this incident, the teacher made a major mistake…” [Emphases mine.])

To reiterate, the Principal believes “it’s normal” “to incite fear and apprehension in students” and that is “for their own good.” (Click here for an article about the same incident in English.)

This March 7, 2020 article is about how 34 students — most of them little sixth graders — made cuts to their wrists for poor results in a test. This quote from the teacher — justifying her action — echos that of Principle Bhujel above: “विद्यार्थीलाई अलिअलि डर त देखाउनै पर्यो ।” (“Obviously, one must instill some fear in students”). She does add that she made a major mistake and would like to be forgiven. Furthermore, according to this article, she was arrested.

But, to reiterate, the young children cut themselves voluntarily standing on the benches in the classroom. If they didn’t, she had threatened to make the cuts herself. Imagine how much the children must fear her. Imagine the fear she must have instilled in them! Unconscionable!

In this article contrasting the education outside — at his Dalit (blacksmith) friend’s workshop — with the one in school, the author says, “हामी स्कुल जानेहरूको पढाइमा […] मात्र डर थियो, त्रास थियो।” (” In the education we were getting in school, there was only fear, apprehension.”)

These are but just three examples. If you are interested, I have a twitter thread where I document such incidents.

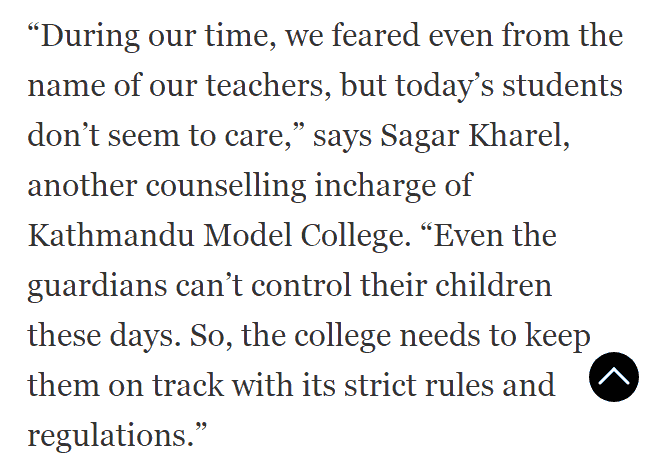

Back in September 2019, The Kathmandu Post, reporting on a harassment issue at what’s called Higher Secondary Schools (equivalent to the last two years of high school in the US and sixth form in the UK), a staff — a counselling in charge — at one such school nostalgically recalled the following:

In that this school actually has a counselor is an exception. I suspect more schools in Nepal have a personnel called a Discipline-in-Charge (DIC) — someone who enforces those “strict rules and regulations” by the threat of physical violence — than a counselor however.

The level and extent to which Nepalis are educated, raised and do grow up to be afraid of and deferential to those the society has deemed worthy of respect through fear, in my opinion, is really unhealthy. How readily and easily do young Nepalis, including young adults, question those older than them, whether they are members of their family (like a father, mother or uncle) or someone else? How readily and easily do Nepalis who know and believe themselves to be of lower status, for whatever reason, question or challenge someone of higher status? Not readily or easily, and as a society we are paying a price for that. For example, we end up with really highly incompetent old men — yes MEN — belonging to the hill Hindu so-called high caste in positions of power and influence for inordinately long periods of time.

But, no one should be fearing anyone else that way, or be respecting anyone out of fear. “Nothing [indeed] is more despicable than respect based on fear” just as Albert Camus declared.

In my opinion, the other reason behind the prevalence of physical violence and violence in general in Nepal is the lack of empathy, lack of compassion. Ironically though, Nepalis who are NOT proud to declare “Buddha was born in Nepal” probably represent an insignificant minority. Buddha, of course, introduced the concept of non-violence and compassion to the world!

Back in September 2019, at another private school I was conducting my teacher education workshops at, I discovered the school believed in and meted out physical punishments. I even observed an administrator using it on children. Once, during break, a student came looking for “The Stick” in the coordinator’s room where I was. He asked me if I had seen it. A teacher needed it to punish a child with.

Anyway, during one of the workshops, I declared, “If Nepali adults insist on using corporal punishments, because we believe it works, we should use it on adults and not on children.”

“Why?” they asked!

“Well” I told them, “It’s simple really. Nepali adults seem to understand it and believe in its efficacy while children don’t!”

Of course, no one said a word. I am sure they felt my logic was ridiculous if not completely flawed!

That they wouldn’t be willing to subject themselves to such punitive action and pain just goes to show, among other things, their lack of empathy, their lack of compassion. Additionally, Nepali adults know that it won’t work on adults but don’t seem to know that they do not produce the desired results in children either! Children, because of where they are developmentally, struggle to connect the pain arising from a punishment with the expected behavior. A lesson not learnt, is a lesson not taught.

So, I followed that up with a question, “If you don’t want it used on you, the children probably don’t want it used on them either, no?”

Invariably and naturally, the question they then ask is: “How do you make children listen to you and respect you without scolding or beating them then?”

“Easy,” I say every time, “Just listen to them!”

A variation on this question I have had also from teachers and adults in Nepal is this: “How do you make children respect you without ‘disciplining’ them?” (“Disciplining” in Nepanglish includes physical violence.)

My response: “Show them respect: listen to them!”

I spent almost two decades of my teaching career without instilling, in my students, any fear-based respect for me. I have raised my eight years old nephew also without instilling any kind of fear-based respect for me. How? Simply by listening to them.

What do you think?