We have a Sanskritic Nepali proverb about the way we should treat guests. It goes like this: “Athiti deva bhawa” (“A guest is God”).

The way we treat foreigners in Nepal — whether short term visitors or long-term residents — is really that in action. I am NOT exaggerating! But when it comes to treating our own, in general, it’s a different story all together.

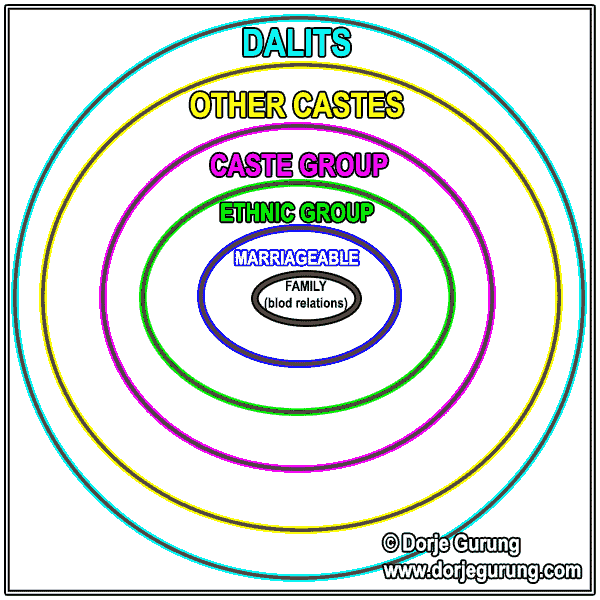

Nepali society is highly stratified — along a number of lines such as caste, gender, sex, age, wealth, sexual orientation etc. — and also highly patriarchal. As a people and society, we are pretty closed and inward-looking. We move, interact, and rely on mostly with people within a pretty small social circle (see image below).

More often than not, for Nepalis, those within the first three concentric circles are the “us” while those outside are the “them.”

Nepalis generally being considerably more discriminatory, prejudiced, and misogynistic against, and judgmental of their own people than of others is but one of the many consequences of — and evidence for — precisely that.

Let me take you on a little exploration here. Let’s take all the Nepalis who have NO issues with fraternizing and having relationships — including romantic relationships — with foreigners. I have absolutely no sense for the number or percentage of my fellow 29 million Nepalis who would fall into this category. Do you? It could be 1 million or 10 million. Who knows!

For argument’s sake though, let’s just assume they number two million adults. Let’s also assume that these Nepalis, on average, are considerably more progressive — that they are more open and outward-looking — than the rest.

Let me next ask you to consider a series of questions about them.

What percentage of those Nepalis socialize and fraternize as readily and easily with fellow Nepali staff who is poorer, a different gender, or occupying lower positions in the office as they would foreigners ticking those very same box or boxes?

What percentage of them would be as non-judgmental of — or would not gossip about — fellow Nepali’s choice of profession/net worth/partner/marital status/friendship/alliances/sexual orientation/gender identity etc.?

Let’s also assume that those two million Nepalis would readily invite foreigners, especially white foreigners, into their homes for meals, and also to family, community, and religious gathering, events, and functions etc.

What percentage of those Nepalis (would) invite fellow Nepalis they consider to be of “lower caste” to the same as readily?

How many of those two million Nepalis would as readily walk into a Dalit’s house for meals as they would to a foreigner’s, or accept food items from a Dalit as they would from a foreigner?

What percentage of those two million Nepalis would NOT object to someone from their family marrying a fellow Nepali from a different caste, especially one considered to be of a lower caste than them as they would not a foreigner?

What percentage of those Nepalis would hesitate to take advantage of or dupe, swindle, or even commit crime against a fellow Nepali as much as they would against a foreigner?

Let’s next explore issues and questions about our views and treatment of females.

To start off with, because we assumed they are considerably more progressive, it’s probably a safe bet to also assume that all of the two million Nepali adults accord foreign females — especially White females — a high level of respect.

But, what percentage of these progressive Nepalis, however, would accord the same level of respect to fellow Nepali females over the board, like to even women belonging to the “lowest caste,” for example? (That is NOT to insinuate that white females should NOT be respected.)

What percentage of those Nepalis would be as non-violent verbally, emotionally, and physically towards female Nepalis as they are likely to be towards foreign females in country?

In every case, I suspect the answer will very likely be significantly less than 100%! In other, nowhere near all of those two million adult Nepalis’ would be as accommodating of fellow Nepalis in general as they are of foreigners.

As for the rest of the population of the country, on average, are likely to be even more discriminatory, prejudiced, misogynistic, and judgmental of fellow Nepalis. (Of course, among them are very likely Nepalis who discriminate against foreigners but not against fellow Nepalis, for whatever reason.)

Be that as it may, strictly speaking though, were Nepalis to REALLY follow the dictates of the highly patriarchal Brahmanical caste system, we should be treating our foreign guests the worst!

According to the system, ALL foreigners are outcastes, and women, in general, are inferior to men. Outcaste are outside the system and, therefore, below Dalits, the untouchables. In diagram above, foreigners would fall outside the light blue circle.

Interestingly though, there was a time when a category of foreign visitors were viewed and treated as untouchables, not as Gods. And that time was when the country first started receiving international visitors — towards the middle of the last century, when it was just emerging from what is described by some as the “Dark Period.”

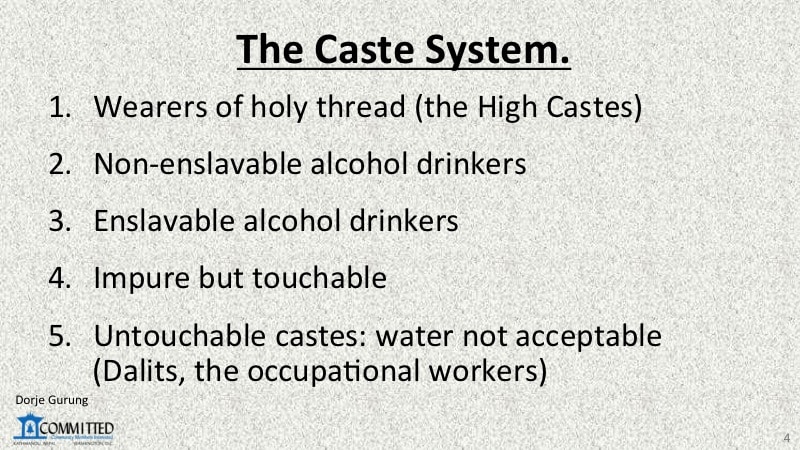

In 1951, the country had just been freed from the clutches of the iron-clad rule of the hereditary, feudalistic oligarchs — the Rana (so-called high caste) families. The country had been under their oppressive rule since 1846. The main goal of the oligarchs, not surprisingly, had been to consolidate and maintain their power and thereby exercise and maintain the supremacy of the so-called high castes. To that end, they had promulgated the fragrantly discriminatory Muluki Ain of 1854. It divided the people into five castes and legitimized the caste system (see image below).

The system also assisted them in their second goal: the exploitation of the population (enslaving some, for example), using the country as basically their playground, and plundering its resources for their own benefit. They kept the population completely in the dark (such as by not providing any education) and held them back from making social, economic, and political progress. Caste-based beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, practices, and protocols dictated most people’s everyday lives and even down to the layout of villages, communities, and residential areas.

As Liechty reports in Far Out, when emerging from the 104-year feudal Rana rule, Kathmandu didn’t even have eateries. Quoting an earlier (2005) work of his he says, “Because of Nepali concerns over ritual purity (imparted by unknown cooks and foods), Kathmandu had essentially no restaurants until the 1950s and the arrival of of new transient population [the tourists] (Liechty 2005)” (140).

To give another example, so strong was the preoccupation with and so important was the concept of “ritual purity” to the hill so-called high caste Hindu rulers that they had instituted a purification ritual, involving isolation, for Lhasa Newar traders following their return from Tibet (see image below).

Likely a majority in Kathmandu valley at the time, Newars also had their hierarchical social system. They had their own Newar so-called “low-castes.” They would treat others too with disdain, such as the ethnic Tibetans (Bhotes) from my village, at least in Pokhara, according to my older relatives.

Such attitudes and practices partly led to the budget tourists fortuitously providing the people of Mahruhiti, the low-caste Newars, the opportunity to cash in (excuse the pun) on them. At the time the area was at the periphery, the margins, of the city. As such, an area with mostly the low-caste Newar residents. Liechty, reproducing Tarnoff’s description of the area says of Mahruhiti: “the filthiest, foulest, smelliest street in the world (Leichty, 2017: 161).” But it was close to Swayambhu — one of the popular tourist destinations — and got a lot of tourist traffic!

Bishnu Dhoj Shahi, a low-caste Newar, was the first one in the area to capitalize on them.

‘It seemed ironic that an untouchable man, from a neighborhood most locals deemed godforsaken, was among the first Nepalis to tap into the budget-tourist market. But, as an elderly low-caste man remembered, “Tourists didn’t know about jat [caste status] so they didn’t care where they statyed or where they ate.” Bishnu shahi conceded that his vicinity was primitive. “But still it attracted hippies because they had no ijjat.” Ijjat connotes prestige, status, or reputation and is often linked to caste standing, For Shahi, saying that hippies had no ijjat was not an insult but a simple observation that he and they were willing to interact as social equals. While the Royal Hotel and other multi-star establishments were heavily invested in prestige (and literally dominated by Nepali’s royal family), budget tourism started with interactions between tourists and Nepalis at the opposite end of the social/caste spectrum.’ (Liechty 2017: 151)

The caste system says, for example, that the hill so-called high caste Hindus are born into families of prestige, status, and respect — and deserve all that, while others do not — because of what they did in their previous lives!

As the number of tourists started rising, the demand for accommodation also rose. Among the dozens of families opening their homes up to them in Maruhiti, many were low-castes.

Over time, the so-called “higher castes” realized the potential to make some extra money by making adjustments to their attitudes towards — and views of — not just the outcastes but also towards the structures of their home, specifically, the ground floor.

At the end of the chapter, Leichty concludes,

“It is no coincidence that low-caste people in marginal parts of the city were first to tap into budget tourism. Socially they had the least to lose and most to gain from associating with foreigners who, by high-caste Hindu logic, were as contaminated and contaminating as these low-caste people themselves. But they were also the ones with the most to gain from the peculiar economics of budget tourism which is, by definition, about low prices, low wages, and low profits.” (160)

Fast forward to today! Many in Kathmandu probably do not know that before Thamel and Jhonchhe (Freak Street), and long long long before Jhamsikhel (Jhamel), the original tourist district was Maruhiti!

I wouldn’t be surprised if the majority of establishments in Kathmandu catering to tourists and foreign guests in the tourist districts now are — and, since 1990s, have been — owned by the higher castes, whether Newar or otherwise, if not run by them as well! I doubt even a fraction of the establishments tourists have been frequenting over the last three decades are run — forget owned — by the so-called low-castes.

Forget owned and run by the so-called low-castes, by the nineties hotels in Thamel wouldn’t rent out to Nepalis! Kathmandu Guest House wouldn’t even let me visit a college friend staying there!

But of course, were Nepalis still caste conscious in its totality, we would still be treating at least some of the foreigners the way they were by our predecessors.

We make exceptions when it comes to the foreigners because it suits us! Let’s be honest: a deterrent to mistreatment or abuse of foreigners in general is partly their wealth and reach — perceived or real.

Another reason behind the Nepalis’ treatment of and behavior towards foreigners as per the proverb, specifically white foreigners, is changes in our views of and attitudes towards them. Being fair-skinned has always been associated with the so-called high caste and/or wealth, for example. The situation and attitudes vis-e-vis the foreigners changed dramatically partly for that reason.

Ironically, status is associated with having a relationship — or fraternizing — with foreigners, especially white-skinned foreigners! What’s more, many Nepalis likely view them as even being superior to them! So now, far from loss of status, being seen with a foreigner, for instance, is a status booster! Living or having a relative in countries where the white-skinned foreigners are native to is more so and something to brag about around dinner tables at wedding parties, for example. What Nepali doesn’t wish that they could send one of their own to one of those countries, by hook or crook?

I must, however, add that our general attitude and behavior towards, and views of Blacks is not the same. Local Muslims are also considered outcastes and don’t fare anywhere near as well as the White-skinned so-called “outcastes”.

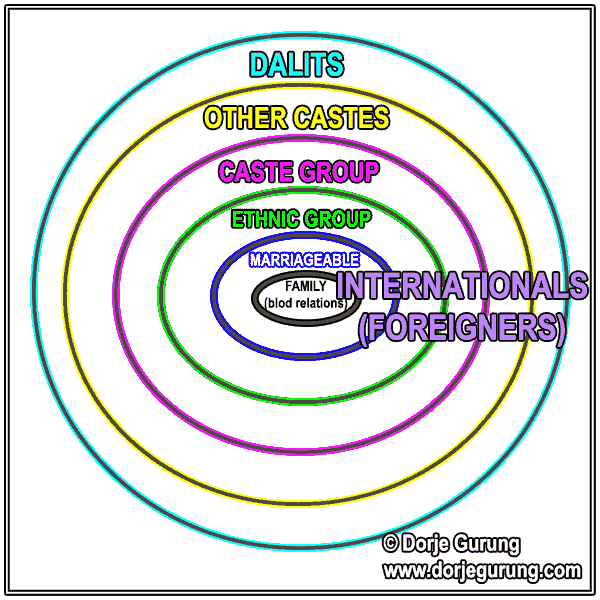

So, in general, the foreigners, while initially, and as per the caste system, would have fallen outside the circle encompassing the Dalits, now they are fluid (see image).

Nepalis still follow the dictates of the caste system really only when it comes to fellow Nepalis. We follow the patriarchal dictates only when it comes to fellow Nepali females.

In other words, as a people and society, when it comes to the caste system, we do what suits us and therefore we are hypocrites!

That’s only part of the explanation though. The other explanation, as I hinted at in the beginning, is Nepalis being closed and inward-looking.

Being closed, we fear the unknown, we fear the “them” — people of other ethnicity, other caste, and their culture, their traditions etc. Our community expects/demands conformity in both thought and behavior from all the members, and we willingly do conform. We resist and/or are unable to readily assimilate/accommodate alternative ways of doing things, new or alternative beliefs, and alternative ways of thinking and being. Our poor education system is also partly responsible for all that.

Being inward-looking, pretty much every group over-inflate the value their culture, their practices, and their beliefs. Even if they didn’t believe that somehow their ethnicity and/or culture is “superior” to all others — or at least somehow “better” and therefore necessary to maintain — many will at least be able to point at ethnic groups or cultures that are “inferior” or “not as good as” etc. Every single group has a group they can call as being below them in the social ladder!

Will a time ever come when Nepalis will revise their views of the “them” — the “inferior” castes — the way we have done of the foreign outcastes?

Those who should be, and stand to benefit the most from being, most open to challenges to their religions, social, cultural, or traditional beliefs, values, and practices are the least, though! In just a little over a generation, as readily and easily as so many of us appear to have modified our views of, attitudes towards, and therefore behaviors with foreigners, we have demonstrated again and again how reluctant we are to do the same when it comes to fellow Nepalis.

I should add that firstly, I am NOT against Nepalis treating internationals (my preferred term for foreigners) as they would God himself/herself; and, secondly, I am all for according females the same respect as accorded to males.

As a matter of fact, I consider myself to be a human being first, so I would be FOR treating every fellow human being just the way one would every other human being for simply being a human being!

Maybe the coronavirus pandemic will provide many fellow Nepalis that insight! When you suffer great pain, anguish, and despair, it can bring insight into life and about the world like no other. I know because I did and it has.

One can always hope!

What do you think?