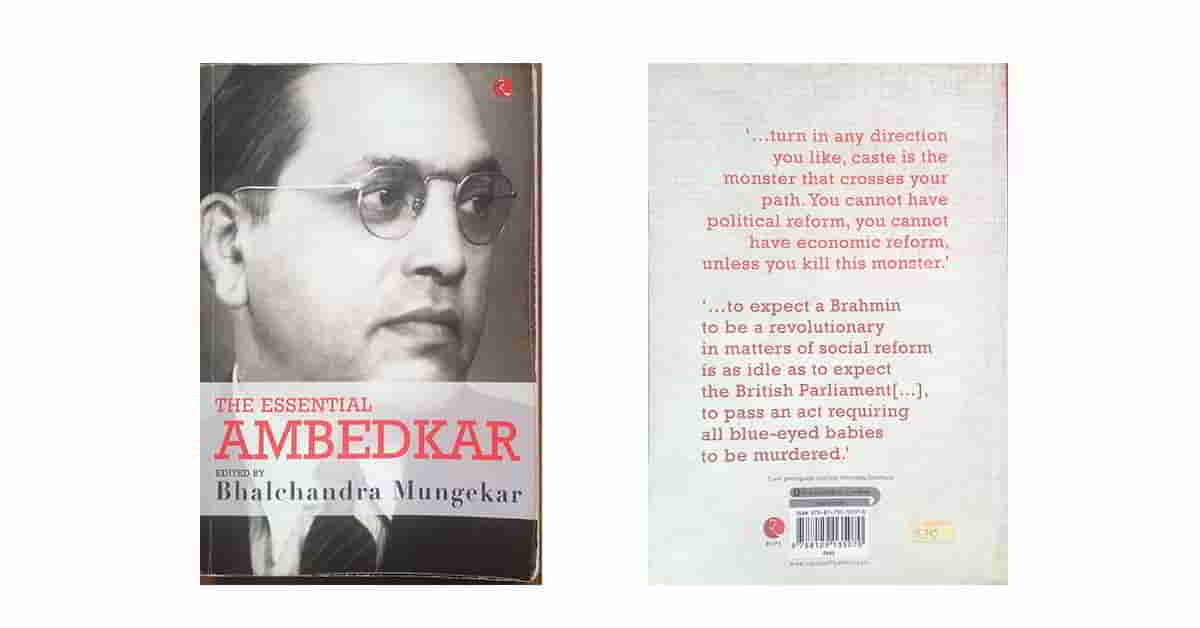

I must confess something. While I have known about Mahatma Ghandi almost all my life, I came to hear and learn about the Father of the Indian Constitution Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956) only after some time following my return to Nepal in May 2013. At some point, I started following a Twitter handle which purports to tweet Dr. Ambedkar’s ideas, opinions, and his published materials. Finally in July 2019 I picked up a book, The Essential Ambedkar, which reproduced a lot of his writing on the caste system and other topics.

Dr. Ambedkar was a Dalit and consequentially suffered a great deal because of that. No wonder, he converted to Buddhism! No wonder, he spent his life working towards the emancipation of the so-called the lowest caste, the Dalits, in the Indian Subcontinental social system: the Caste System.

Apparently, he alone, for instance, was responsible for ensuring provisions in the constitution granting affirmative action (reservation in the Subcontinent) to the marginalized and disenfranchised Dalits and other peoples, more than half a century before we in Nepal would pen such provisions in our own constitution.

In this blog post, I want to reproduce parts of the chapter on Struggle for Equal Human Rights, parts I whole-heartedly agree with. To begin with the “two agencies” that have been relied on to produce “social justice”:

Two agencies are generally relied upon by the social idealists for producing social justice. One is reason, the other is religion.

The rationalists who uphold the mission of reason believe that injustice could be eliminated by the increasing power of intelligence. In the mediaeval age, social injustice and superstition were intimately related to each other. It was natural for the rationalists to believe that the elimination of superstition must result in the abolition of injustice. This belief was encouraged by the results. Today it has become the creed of the educationists, philosophers, psychologists and social scientists who believe that universal education and the development of priting and press would result in an ideal society, in which every individual would be so enlightened that there would be no place for social injustice.

History, whether Indian or European, gives no unqualified support to this dogma. In Europe, the old traditions and superstitions, which seemed to the eighteenth century to be the very root of injustice, have been eliminated. Yet social injustice has been rampant and has been growing ever and anon. In India itself, the whole Brahmin community is educated, man, woman, and child. How many Brahmins are free from their belief in untouchability? How many have come forward to undertake a crusade against untouchability? How many are prepared to stand by the side of the Untouchables in their fight against injustice? In short, how many are prepared to make the cause of the Untouchables their own cause? The number will be appallingly small. (p. 114)

When it comes to Nepalis, a majority still believe in superstition and are guided by them.

Additionally, we could probably ask the same question of the Brahmins (and Chhetris) in Nepal. The high castes, the Brahmins/Bahuns and the Chhetris, the Khas-aryas, have, after the Newars, the highest level of education in the country. What percentage of these highly educated Khas-aryas have made their life’s mission to contribute towards eliminating Nepali society of the pernicious effects of the Caste System? I imagine an insignificant percentage. To what level have they engaged in activities meant to contribute towards breaking down the systems and structures propped up and maintained directly or indirectly by the caste system? I imagine also to an “appallingly small” level!

Ambedkar goes on to describe why reason fails.

Why does reason fail to bring about social justice? The answer is that reason works so long as it does not come into conflict with one’s vested interests. Where it comes into conflict with vested interests, it fails. Many Hindus have a vested interest in untouchability. That vested interest may take the shape of feeling of social superiority or it may take the shape of economic exploitation such as forced labour or cheap labour; the fact remains that Hindus have a vested interest in untouchability. It is only natural that that vested interest should not yield to the dictates of reason. The untouchables should therefore know that there are limits to what reason can do. (pp. 114-115)

In Nepal, one of the many consequences of the abysmally poor quality and level of education has been the inability of the vast majority of the population to reason logically and understand the spuriousness of the logic behind the Caste System, for instance.

The religious moralists who believe in the efficacy of religion urge that the moral insight which religion plants in man whereby it makes him conscious of the sinfulness of his preoccupation with self and thereby of the duty to do justice to his fellows [sic]. Nobody can deny that this is the function of religion and to some extent religion may succeed in this mission. But here again there are limits to what religion can do. Religion can help to produce justice within a community. Religion cannot produce justice between communities. At any rate, religion has failed to produce justice between Negroes and whites, in the United States. It has failed to produce justice between the Germans and the French and between them and the other nations. The call of nation and the call of community has proved more powerful than the call of religion for justice. [Emphasis mine.] (p. 115)

It’s not much different in Nepal. Ambedkar continues…

The Untouchables should bear in mind two things. Firstly, that it is futile to expect the Hindu religion to perform the mission of bringing about social justice. Such a task may be performed by Islam, Christianity or Buddhism. The Hindu religion is itself the embodiment of inequity and injustice to the Untouchables. … Secondly, assuming that this was a task which Hinduism was fitted to perform, it would be impossible for it to perform. The social barrier between them and the Hindus is much greater than the barrier between the Hindus and their men. (p. 115)

What of the Hindu privileged classes whose “enlightened self-interests” the “[u]ntouchables are asked to trust”?

As to the privileged classes, it would be wrong to depend upon them for anything more than their agreeing to be benevolent despots. They have their own class interests and they cannot be expected to sacrifice them for general interests or universal values. On the other hand, their constant endeavour is to identify their class interests with general interests and to assume that their privileges are the just payments with which society rewards specially useful and meritorious functions. They are a poor company to the Untouchables, as the Untouchables have found in their conflict with the Hindus. (p. 116) [Emphasis mine.]

So what are the Untouchables to do?

What must the Untouchables strive for? Two things they must strive for is education and spread of knowledge. The power of the privileged classes rests upon lies which are sedulously propagated among the masses. No resistance to power is possible while the sanctioning lies which justify that power is accepted as valid. While the lie which is the first and the chief line of defence remains unbroken there can be no revolt. Before any injustice, any abuse or oppression can be resisted, the lie upon which it is founded must be unmasked, must be clearly recognized for what it is. This can happen only with education.

The second thing they must strive for is power. It must not be forgotten that there is a real conflict of interested between the Hindus and the Untouchables and that while reason may mitigate the conflict, it can never obviate the necessity of such a conflict. What makes one interest dominant over another is power. That being so, power is needed to destroy power. There may be the problem of how to make use of power ethical, but there can be no question that without power on one side it is not possible to destroy power on the other side. (pp. 116-117)

At the social level, Dr. Ambedkar, on page 45 succinctly lays out the “real remedy for breaking caste”:

The real remedy for breaking caste is intermarriage. Nothing else will serve as solvent of caste. [Emphasis in the original.]

And yes, I agree with that completely. In Nepal, however, we have a long way to go with that. Forget about those who believe in their superiority relative to a Dalit, an Untouchable, being open to their children marrying into them, the lowest caste. Nepalis are NOT even open to their children marrying into families belonging to just a so-called lower caste!