At the end of his second grade, my little nephew came home with the above certificate and proudly showed it to us all.

And the secret to raising a “Best Discipline” toddler of the year? Not “disciplining”!

“Disciplining” is within quotation marks because its denotations and connotations in Nepanglish is a little different from English! To begin with, it is pronounced slightly differently: the second syllable — sci — is pronounced the way the word she is.

As for its denotations and connotations, for example, a student, child, or a younger individual who obeys the directions and orders given by an adult — an older sibling or relative, a parent, a guardian, a school administrator, or a teacher etc. — is labeled as someone who has “discipline”! A student, child, or younger individual who doesn’t question or challenge authority, doesn’t talk back, or faces an adult with a slightly bowed head (instead of looking straight into the adult’s eyes) is characterized as someone who has “discipline.” And finally, a youngster who follows all the directions, rules, and regulations without questioning “Why?” is also held in high esteem as a “disciplined” person! See what I meant?!

(Since returning to Nepal, I have discovered that I am viewed as an “undisciplined” person because I question everything — our cultural, traditional, and religious practices, our beliefs, and even those who are older than me!)

To most in Nepal “disciplining” children connotes threatening them with — and for many meting out — emotional and/or physical violence. When I was growing up in the nineteen seventies and eighties, attending St. Xavier’s School, violence against children, both at home and school, was routine. Hardly any significant changes to those practices appear to have taken place since then in spite of the fact that corporal punishment in schools was even outlawed in 2005.

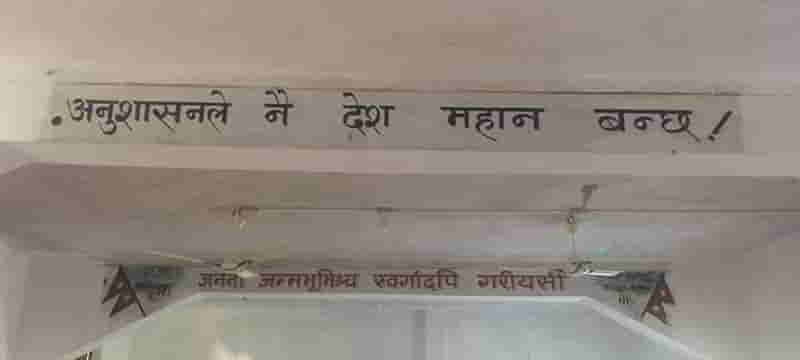

Nepalis still will tell you that if you don’t “discipline” children — i.e. control them, by scolding them or through violence, or by humiliating them in front of their peers or siblings — they will misbehave and won’t learn what they are supposed to, and instead grow up to be a undeserving and burdensome (read unpatriotic) citizens of the country! The final bit is a leftover from the days of the autocratic rulers of the old (see image below).

Apparently, “[a] UNDP report in 1998 showed that 14 percent of school dropouts in Nepal claimed to have quit because they feared a teacher.” A teacher at one of the schools I was running my teacher education program not long ago told me, as a matter of factly, “Here [at the current school], if I don’t punish them physically, they won’t respect me.” No child should be fearing their teachers or respecting their teachers out of fear.

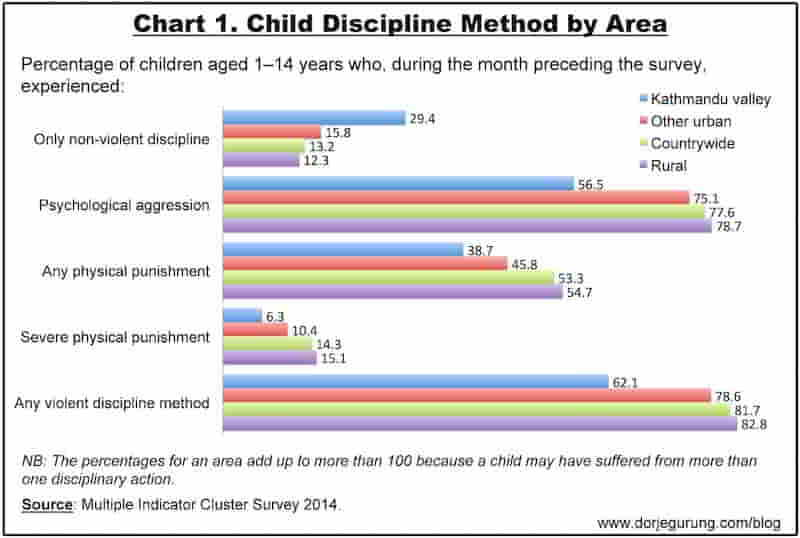

A study published in 2004 found violence in schools to be widespread. In another study conducted in 2006, over 80% of student involved reported being beaten by their teachers. According to the results of 2014 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, over 80% (4 out of 5) children between the ages of one and fourteen had suffered from a “violent discipline method” the month preceding the survey (see green bar in the bottom row labeled “Any violent discipline method” in the image below).

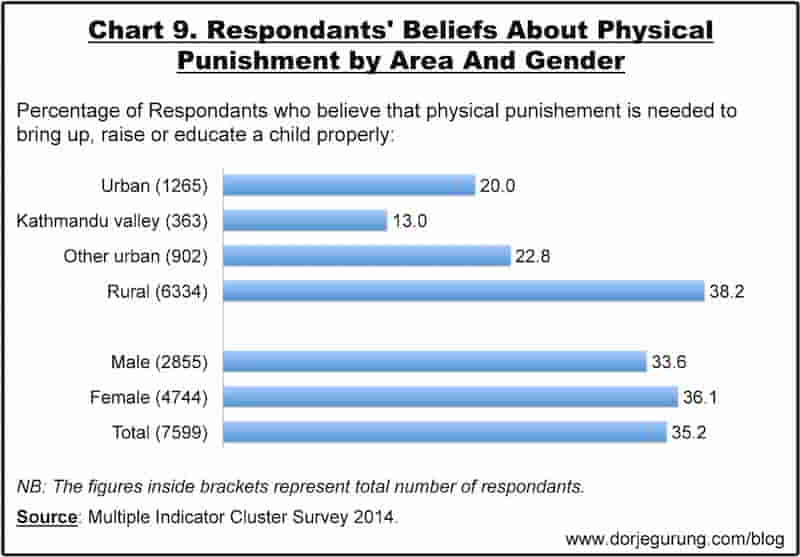

The same survey discovered that slightly over 35% of the respondents believed physical violence to be necessary in raising and educating children (see image below).

Our child-rearing and school cultures control and herd the young — as poorly educated and products of our culture as majority of the guardians and teachers themselves are — and instill an unhealthy fear of and unquestioning deference to those older than them.

It’s no wonder we have young adults who struggle to engage with older adults both in formal as well as informal social settings, for example.

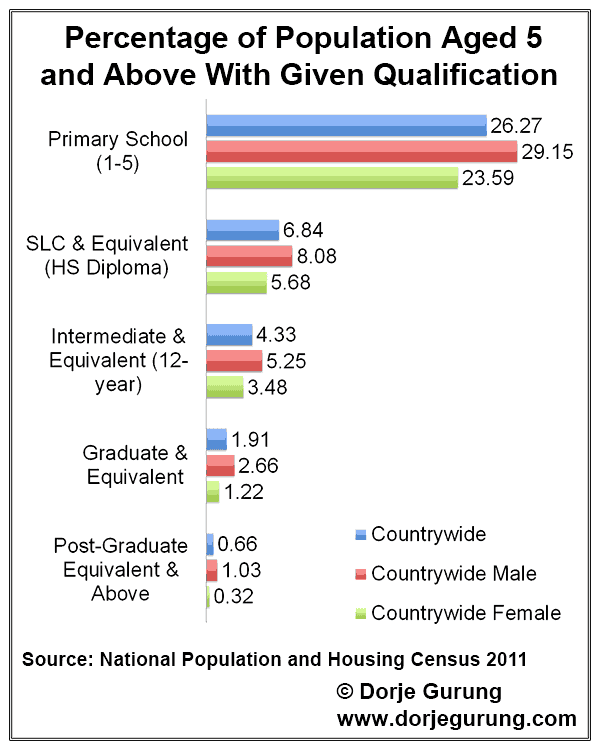

When it comes to the level of education of the population, according to the 2011 census report, Less than 8% of Nepalis aged five and over have twelve or more years of education.

Returning to my little nephew…when he came along over eights years ago, I threw out the window pretty much all our cultural prescriptions on how to raise him. I did NOT allow OTHERS at home or at his school to follow them either. Forget about talking about or using the word “discipline”. Going to read to his class when he was a six-year old first grader, for example, the school wanted me to talk to them about “discipline.” Of course, I didn’t. If I am able to have my way, he will NEVER be introduced to the word and its Nepanglish meanings.

For one because I myself suffered from it all and was completely put off by it. For another because, in my entire previous teaching career of fifteen-plus years, including stints in Nepal, I did not engage in any of that, ever.

Violence has NEVER been part of who I have been as an adult, period! Nor have I sought fear-based respect for my self! Far from it!

And, finally, because I am trying to raise him to be, as I have shared elsewhere, a compassionate human being, among other things!

So, raising my nephew, more than directing and issuing orders at or making demands of him, I have been doing my utmost to guide and mentor him by, among other things, modelling behavior I want to instill in him. In the process, he has taught me how best to do that for him.

Naturally, because we have raised him without any violence of any kind, he isn’t violent with us either. There’s no passive aggressive behaviors, something Nepali children learn from the adults because it’s a culture-inculcated trait of many Nepalis. He doesn’t throw temper tantrums having weened him off of that even before he turned 20 months old using a technique I hit upon then.

Instead, he asks and negotiates and inquires because that’s what he has learned to do from me. My approach, detailed in this reproduction of a session I had with about 50 parents, has been the following: Respect, Listen, and Engage.

There you go! That’s how to raise a best “discipline” child without “disciplining”! And to reiterate something I have said elsewhere, I am NOT an outstanding guardian to my nephew nor an incredibly gifted teacher. No sir! I wish I were. And if I can raise a child without “disciplining,” you can too. However, if you need more tips, check out the blogs under the category Nepal Education and Parenting.

Having said all that, I am completely aware that the connotation of the “Best Discipline” certificate recipient must be someone “very docile and quiet, unquestioningly obedient, and blindly respectful etc.” all of which I DON’T want him to be. And he isn’t!