In an ideal world, I would have grown up to be an artist, a performing artist.

I could have been acting, singing, dancing, and possibly even drawing and painting now! But, of course, we don’t live in an ideal world. The seventies and eighties of Nepal, the world I was growing up in, was very very far from the ideal.

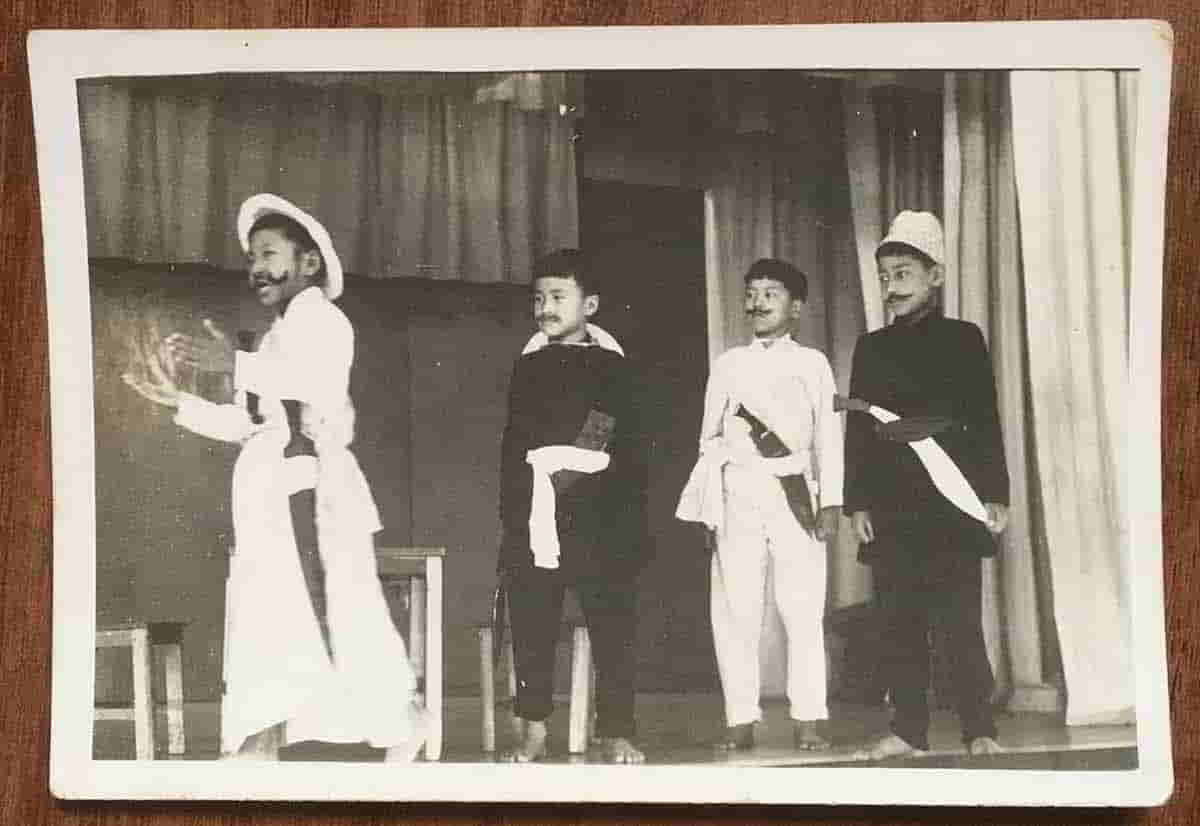

As a primary school student at St. Xavier’s Godavari School in Kathmandu, I discovered I enjoyed and was also good at performing arts — especially acting. The first time I remember realizing acting gave me a kick was right after my performance of the play Bir Balbhadra (Brave Balbhadra). I had been in grade four at the time and we had performed that play at our Parents Day show. It had been the second play I had acted in at the school. The photo above is from that play.

In the three-or-so act play, I played the central character of Balbhadra Kunwar, a war hero.

Kunwar, with help from just several hundred under him, including women and children, tried to defend the fort of Khalanga Nalapani from the few thousand strong British army during one of the many Anglo-Nepalese clashes.

First from the left, arms stretched out in front, in the photo I am walking across the stage, exuding a great deal of confidence — both as the character and the actor — delivering my line. The three standing on the right, shoulder to shoulder, facing the audience, were playing the characters of three army personnel under my character’s command.

There was cheering and clapping from the audience during the performance and more at the end.

Post Parents’ Day show too, I got a lot of attention and accolades from those who had been in the audience – mainly parents and older siblings of classmates, in particular the older sisters of a classmate. All that filled me with pride and a sense of accomplishment. The play, after all, had been the main attraction of our show.

Even though by then I had been recognized by my classmates as actor, playing the character of Bir Balbhadra finally cemented it. From then on I relished being on stage — acting, singing, reciting poems etc. In grades 5 and 6, no different from grade 4, I was selected to play the main character in the Nepali plays.

Apart from being able to show off a skill I discovered I had, acting boosted my confidence and, most importantly, helped me escape…from my own self!

I could be someone else, in a way. Playing a role, playing other people and dealing with their angst and issues, served as an outlet for some of the angst I myself felt as a young boy, suffering as I was from a number of personal issues.

In fourth grade, for instance, I had been ostracized by my classmates over a minor incident involving two other classmates.

Part of that year I had ended up spending most of my time with older school mates. At the time itself, I had come to conclude — rightly or wrongly — that the incident had been a result of my being a Bhote (ethnic-Tibetan in Nepali). I suffered from a lot of insecurities and issues of low self-esteem, some stemming from my ethnic identity. I had learned — even before attending Godavari School — how Nepali society viewed the likes of me.

I belonged to a “backward” caste — one of the many derogatory connotations of the ethnic designation — and, Nepali society deemed, I deserved the label.

I knew my people had adopted the surname “Gurung” because of that. They pretended to be some other people to prevent others from looking down on us or from discriminating against us. But I had a Tibetan first name! Consequently, I suffered from a major crisis of identity in Nepal until I left for Italy in 1988.

Along with the rest of the ethnic Tibetans from my district, I had been made to feel shameful about everything associated with our culture, heritage, and identity — and I did. (It would be years before I learned — and internalized — that the shame was NOT mine to carry but theirs!)

Also that same year, my maternal grandfather — the person for whom I had been the center of his world — had died.

I had always loved and adored him just as he had me. As a matter of fact, early on in my academic career at the residential primary school, when at times I would cry myself to sleep at night in the dormitory, it would be because I missed him.

Another issue had been my struggles with my relationship with my parents.

Some of the struggles stemmed from the family being poor, no different from the struggles of most other poor families in the country.

Compounding that was the fact that I had next to no adult with whom I was able to talk to and express myself – my angst, my issues, my dreams, my drive, my energy, my power. As I grew older, I realized how my grandfather would have been that adult who I would have been able to count on to listen to me.

Though I was determined to break out of the mold of a Bhote, I could do or say little about this to others, for example. I also felt I couldn’t say or do anything in defiance of — or as a protest or railing against — the Nepali social order and system. And I didn’t. Acting in plays was the “out” I needed, sought, and got.

There was also the shame associated with being from a poor and uneducated family. There was however, something far worse than all of that.

And that most shameful thing was bed-wetting!

I dreaded going to bed and waking up in the morning — sleeping, as we were, in dormitories in night dresses! This lasted about SIX YEARS — five as a boarder at Godavari School and one as a seventh grader living at a local hostel while a day-scholar at St. Xavier’s Jawalakhel School.

Waking up and discovering that I had indeed wet my bed, which happened more often than NOT, was the worst!

The first three years, waking up in the morning in our night dresses was followed by changing into day clothes and walking to the “shelf-room” where our toiletries and other clothes were stored. The absolute dread in that routine, on the mornings I woke up in a wet night dress and bed, was queuing up outside the dorm and making that very long walk smelling of urine! Apart from it being one of the most — if not THE most — shameful things I endured regularly, I was griped by a morbid dread of someone finding out — like a teacher or a fellow student — and being humiliated in front of everyone.

I constantly also worried if others knew.

If others knew, who and how many. After all, I did know of a classmate who was also a bed-wetter! Since I knew of one, it stood to reason that others also knew about me. Plus, I agonized over the possibility that those who knew must be talking about it behind my back calling me “Mutuwa” (bed-wetter). I was, after all, a very sensitive boy. Another reason the child in me wanted to go to the US for further studies was to “escape” from all this and more. All of that, I am pretty sure, contributed to my being the very shy boy I was around adults, and especially around girls and women,

Strangely enough, I don’t have a single recollection of any teacher finding out and humiliating me in front of others.

(One of the “teaching tools” teachers used at St. Xavier’s — as, I am sure, also in other schools at the time — was public humiliation. The culturally-sanctioned belief in Nepal is that, if you humiliate a child in front of others, they’ll learn their lesson and won’t repeat the “mistake” again.) Neither do I have any memory of fellow students letting on, in any way, that they were aware of that habit of mine.

HOWEVER, it’s entirely possible that I may have completely blocked out and forgotten about any or all such incidents, for the simple reason that they would have been incredibly humiliating and possibly even traumatic.

Returning to the photo…if you look closely at my face, playing the character of the very brave (bir) and courageous historical figure, you can see me exuding a determination, a confidence that I normally wasn’t able to show or demonstrate in real life in front of many, for example.

Moving on to Jawalakhel School, the secondary school, acting opportunities didn’t come that often. Opportunities for other creative outlets were also limited. I rarely sang, I rarely participated in elocution contests, I rarely participated in art/painting contests etc. – activities I engaged in a lot as a primary school student.

Lack of opportunities and coupled with the belief — in the Nepali society of the nineteen eighties — that being in the arts, being a performer, was to live a life of struggles, I just kind of abandoned engaging in them. At the time, artists and performers in Nepal could count on very limited scope and demand for their skills, services, and products.

There were maybe three actors – Shiva Shrestha, Bhuwan KC and Neer Shah — in the entire country who, as far as I knew, made a living out of their art. (The three incidentally belong to BCN trio (Bahun-Chettri-Newar) — three of the four groups that have consistently scored the highest in the Human Development Index.)

Only one musical rock band – called Prism – existed. Their struggles pretty much everyone seemed to know. No different from pretty much everyone else, I knew of no contemporary painter in the country!

Besides, I belonged to the “wrong” ethnicity and caste! There was certainly no ethnic Tibetan actor or musician or artist that I knew of or was in any way popular, forget popular nationwide!

So, instead of a performing artist, I dreamt of becoming an engineer. Being one of the top students in the class, the goal was completely in line with societal expectations. Top students were — and still are — expected to study science and become either a medical Doctor or, failing that, an Engineer.

But, what do I end up becoming? A teacher…which of course was a source of disappointment for my family. Teaching, in many ways, however involves “performing”!

NB. This is a revised version of a story I wrote for a writing class I took early last year..