On day two of my release from jail, I became aware of the trauma-engendered feelings of pain and rage. What I didn’t know then was what would trigger those feelings or how those feelings would manifest themselves. I didn’t know, for example, that the pain would be triggered by the memory of a fellow inmate, by songs, and by others’ pain and suffering and that they would make me cry. I also didn’t know, for example, that the rage would drive me to do and say things — both on and outside social media — with a much heightened sense of urgency and passion.

What I also didn’t know was that the traumatic experience had engendered another feeling.

Friday, Feb. 22, a truck hit the rear-left wheel and bumper of my car. A traffic police got the registration (blue book) from the young driver and handed it to me saying, “The damage is not that big. Go settle it between yourselves.”

To make a long story short, we weren’t able to settle it. The guy found the estimate too high! The mechanic told us that we had to register the accident at the nearest police station if we want to involve the insurance company. Nothing came of the visit to the Tinkune Police Station though. It turned out, we were supposed to have gone to the nearby traffic police station instead. As it was pretty late already, we parted agreeing to meet there the following morning.

The next morning, Saturday, approaching the traffic police station, I decided all the hassles of registering the incident and involving the insurance company etc. were not worth it. I decided I wouldn’t mind going back to the Hyundai Service Center we had been to the previous day, getting a new lower estimate, and settling on a mutually agreeable compensation. I called the guy and told him my decision. He agreed.

I drove to the service center only to find it closed. I ended up taking my car to another mechanic my family knows. I shared my decision with the guy, but he refused to come there! He instead insisted on going to a mechanic of his choosing. Plus, he wanted his registration back because, apparently, he was going out of valley Sunday. He promised to fix the damage to my car upon his return from the out-of-valley trip.

I had no intention of returning his registration before my car was fixed. I told him that just that. I refused to entertain his demands and hung up on him as he kept being very belligerent on the phone, asking for my car license plate number and details of where I lived etc.

A little after noon, he calls and tells me to come back to Tinkune Police Station. He tells me that they already have my license plate number and that they have “registered a case against me” with the police.

Saying “Talk to the policeman handling the case” he hands the phone over to him.

Just on pure reflex, I hung up the phone. Immediately, after that I started sensing a general feeling of discomfort permeating through my body. Then, what felt like anxiety replaced the discomfort. Not long after that, I realized what I was really feeling was fear!

The last time I had had a phone conversation with a policeman and had agreed to do what he had asked me to do — namely to show up at the police station — I had been thrown in jail! The combination of the apparent police case registration and the policeman’s voice on the phone had triggered that trauma-engendered feeling.

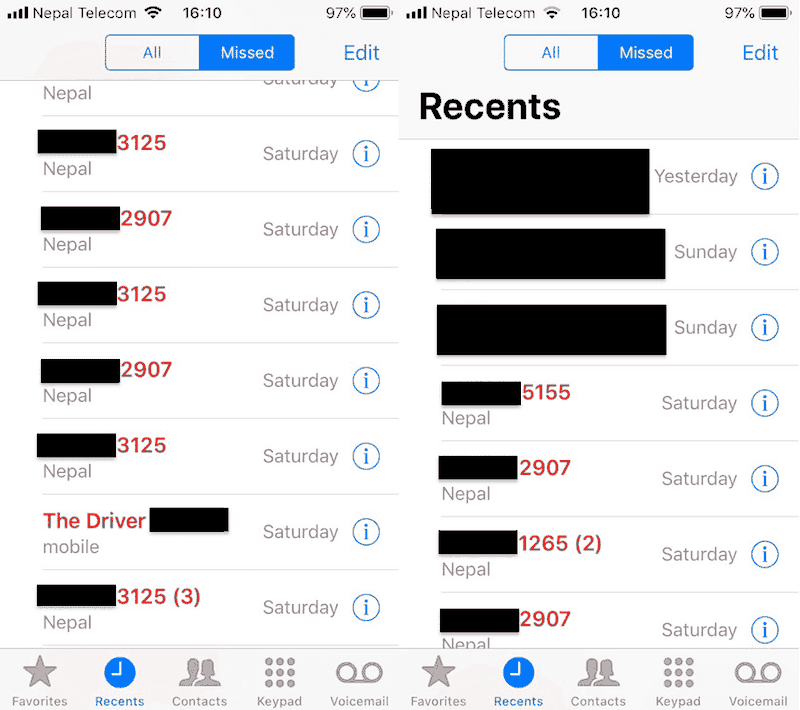

After hanging up on the driver, the rest of the afternoon, in addition to getting calls from him (in the image below “The Driver” as well as the number ending in 5155), I had a total of twelve calls from three unidentified numbers. As you can see, I didn’t answer a single one of them. I was not ready to have any conversation with the driver. I didn’t answer the other calls because I assumed they were all from the police (which I found out Sunday they had been).

Scared to answer the calls and also to go to the police station, I decided to give myself some time to think and prepare. I decided to head out only the next day.

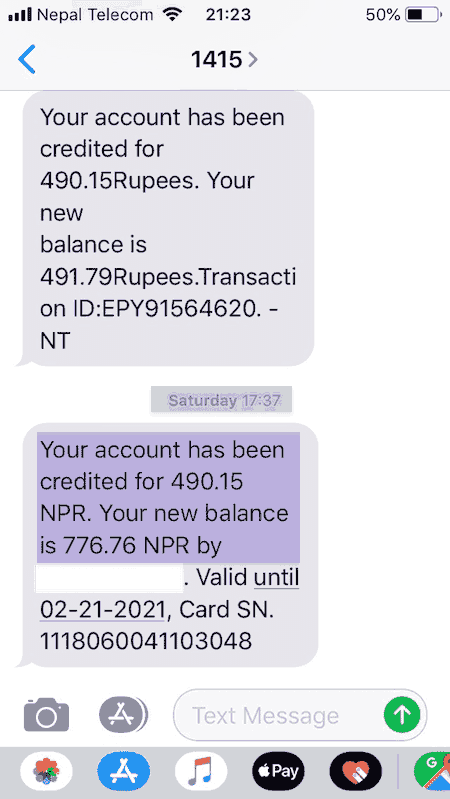

The first thing I did in preparation was to top up my phone that evening.

I feared being stuck with a need to use my phone — whether to call people or to give live updates on social media or to go video-live on Facebook etc. — and not have any credit, the way it had been in Qatar.

Nepal being Nepal, Friday evening itself, when at Tinkune Police Station, I had called a friend asking her if she knew anyone who might be able to help with the predicament I was in. She had referred me to another friend who knew a policeman. The friend himself also very kindly came to the station to provide support!

By the time I showed up at the station the second time around, early Sunday afternoon, I had asked seven friends if they knew any policemen who might be able to help. In circumstances such as these in Nepal, whether you are victimized, or lose out in some way, depends pretty much entirely on who you know and who you have been able to mobilize.

I also tried to recruit people to go with me to the station itself. I ended up with my dad and a friend of a friend. I didn’t ask many friends because I suspected they would all be busy at work.

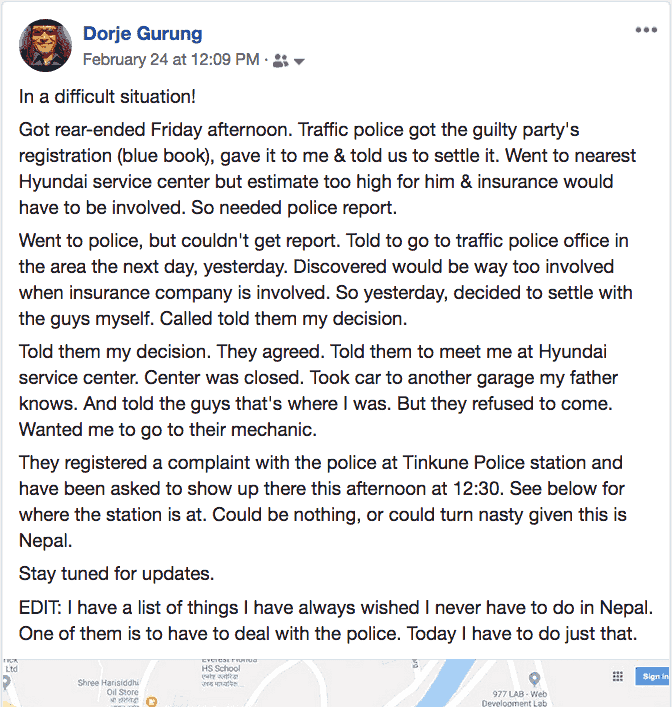

Before I headed out, I took to social media. I made a series of tweets about the accident and how I was heading to the police station.

A story. Got rear-ended Friday afternoon. Traffic police got the guilty party’s registration (blue book), gave it to me & told us to settle it. Went to nearest Hyundai service center but estimate too high for him & insurance would have to be involved. So needed police report. 1/n

— Dorje Gurung (@Dorje_sDooing) February 24, 2019

I followed that up with Facebook posts on my profile as well as the two pages I manage including images of location map for the police station. (Click here for the first one and see image at the top for the second one.)

On the way, I recruited three friends to call me periodically, like at 15 minute intervals but at different times.

Arriving at the station, the first thing I did was to turn on my iPhone voice recorder and slide the phone upside down into the outside chest pocket of my coat. I recorded some of the early exchanges with the police and others.

Why did I do all that? What did I think was going to happen? I actually didn’t really know. Had any of the friends I recruited to call me asked, “Why, what do you think they’ll do to you?” — which no one did — I wouldn’t have had an answer. The fear engendered by my traumatic experience in Qatar, of course, was irrational.

What I do know is that I don’t trust Nepali police. They can be very very arbitrary when it comes to what they do to ordinary people. That’s why I have hoped that I never have to deal — or engage — with the police in the country for any reason. As for the details supporting that…they could be a whole another long blog post on their own.

What do you think?