Growing up in Nepal, I knew I was not “fit” for mainstream Nepali culture and society. I did a lot of pretending — and was in a lot of denial — about my linguistic and cultural identity and heritage among other things, for example. Not long into my secondary school career, I realized, were I to continue to remain in the country, breaking out of the person/personality our society said I could/should be — defined mainly by my birth as a Bhote, a so-called “low caste” ethnic Tibetan — would be an uphill battle that I probably wouldn’t want to fight. The societal pressure to fit THE “bill” would have been way too strong and they would have also functioned as restrictions, hurdles, and barriers to whatever I may want to do and wherever I may want to get to in my life.

Many things also happened in school and in the society — both to me and others that I was a witness to — that I mostly remained silent and did nothing about because of cultural and societal expectations. I was a kid, I was a Bhote. I was afraid of what others would say. “What does a Bhote kid know?!”

The country also suffered from many social issues that, as far as I could see, neither the educational institutions nor the society covered, addressed, forget attempted to resolve. Though not spelled out in black and white, everyone — including high school students like us — was acutely aware of the social consequences to “speaking out” and “stepping out of line.” (Conveniently, we have a stigma against pretty much every social ill our society suffers from and therefore speaking about them is taboo.)

As time passed following my departure from the country for the first time in 1988, little of social significance changed even as a revolution, a ten-year civil war, another revolution, and a violent civil unrest in the southern plains followed one after another.

Finally returning to Nepal, in May 2013, I had come home after spending pretty much all my adult life abroad. I had come home after being educated in four other countries. I had come home after living and working in nine and traveling in about three dozen countries. I had come home after becoming someone I had never imagined even becoming as a young student in Nepal dreaming of going abroad for studies.

Of course, after all that, I could no longer stay quiet and mum about everything I had seen and experienced in the country whether as a child or an adult. After all, even the brief period I had lived and worked in Nepal, in the late nineties for the first and last time as an adult, I had spoken up — in my FM radio program I hosted — about some of the issues the country faced.

This time around, the most traumatic experience of my life — the twelve-day, unjust incarceration in a Qatari jail — has also propelled me to be very vocal.

So, unlike pretty much everyone in Nepal who I have known since childhood, I have been “speaking out” both on social media and elsewhere. I don’t know of a SINGLE Xaverian contemporary (forget about a classmate) residing in Nepal who is as vocal as I am about social justice (the caste system, the structural issues), about gender equality, about our abysmally poor education system, and about violence at home and in schools etc. That however, is understandable. (Additionally, we don’t have a long history of mass activism around a social issue or cause, in general.)

In the conservative and pretty inward-looking society of Nepal, you can’t distinguish yourself too much! Especially not if you do not come from a group that’s already seen, viewed, or regarded as distinguished, if you know what I mean!

In Nepali society in general WHO says is more important than WHAT is said. The criterium for whether one listens to a person — and adds ones voice to and amplifies it — is NOT necessarily based on whether WHAT the person says has merit, but rather whether THE PERSON has “merit.” A person’s “merit” is often social status — based mostly on caste and/or family background, and additionally wealth, age, and gender etc.

If you aren’t a person of “merit,” if you are not already — or recognized as — a member of that club, “No can’t do” says our highly stratified society! You are in no position to challenge the status quo. Certainly not in a position to do or say things that might challenge the status, beliefs, and actions of the privileged and/or well off, and thereby make them uncomfortable. Forget about in any way (even seemingly) disrupt their lives.

When it comes to serious social and structural issues, our society has decided that they are either too small an issue or too sensitive to explore. Our society would rather we pretend we have “unity in diversity” and believe that we “respect each other and live in harmony” just the way our constitution and textbooks say we do, and throttle public discourses on such thorny issues.

And there’s a price to be paid for defying that — for speaking out about such issues and ostensibly “disrupting social harmony” — especially as someone who is not ENTITLED to do that!

No wonder, as far as I can tell, most guys I have known since my childhood at St. Xavier’s “toe the line” or don’t do or say much to “rock the boat” as it were. No wonder, at least to me, the kind of reactions I have gotten from some and the lack of reactions from others to everything I have done and said since arriving in the country in May 2013.

Hell, in Nepal even those with the responsibility of protecting and ensuring the integrity of the judiciary of the country — one of the three pillars of a DEMOCRACY! — don’t say or do anything even when it is being completely and totally compromised for fear of potentially creating friction with family and friends!

Given how the social world and therefore social capital of a well-established person in Kathmandu consists mostly of a pretty finite number of highly interconnected people in the city itself, only the “foolish” would do anything that might bring dissociation, rebuke, antagonism, or, worse, ostracism from others in the network.

And here’s the final thing: for that very reason, had I never left Nepal, I would have probably not even had the courage to express this observation even had it occurred to me!

What do you think?

Jan. 31, 2019 Update

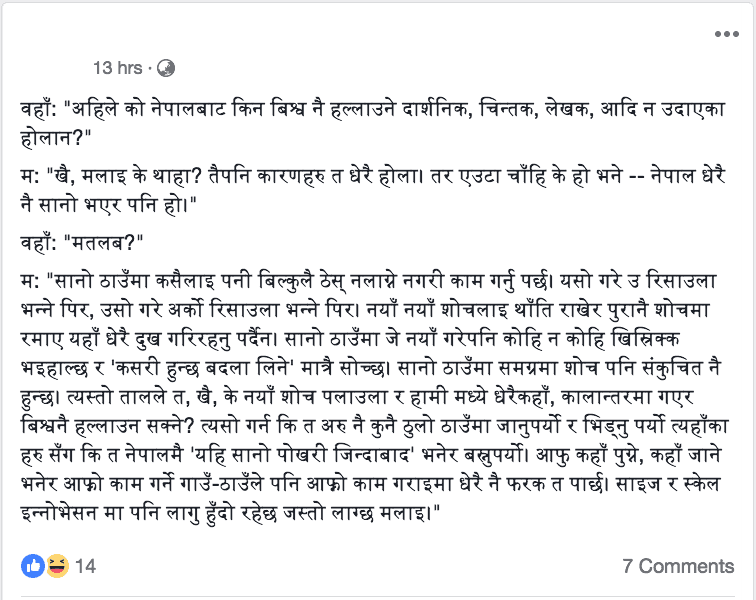

The following image is of a Facebook post by a friend. Sharing an exchange with an individual, the friend characterizes Nepal and a particular aspect of Nepali culture and people which reinforces what I was trying to get at above.

Here’s the translation:

Individual: “Why haven’t we [in Nepal] produced world class thinkers, writers etc.?”

Me: “I really am not sure? Regardless, there must be many reasons. But, one is this — because Nepal is really really small.”

Me: “In a small place, what you do absolutely cannot in any way create even a minor issue or trouble for anyone. Doing this might anger this person, or doing that might anger that other is a constant concern. If you keep any new and novel ideas etc. at bay and instead just keep enjoying thinking and doing things the old way, one does not have to struggle much. In a small place, whatever innovative thing one does, at least someone will take issue with it and will be consumed with the thought of ‘How do I take revenge’! In a small place all thoughts and attitudes are also provincial. At this rate, what are the chances that a great thinker will bud and go on to shake the world? To be able to do that you have to go to a bigger place and engage with such people there, otherwise live in and extol Nepal saying, ‘Long live this little pond!’ Where one gets to in life and where one wants to get to in life, are shaped greatly by where one lives just as it shapes what one is able to do. My sense is that ‘size’ and ‘scale’ also applies to ‘innovation.’ [Emphasis mine.]