Yet another #LifeEh observation. (Click here, here, and here for the others.)

As a secondary school student in the eighties, I had wanted to “escape” from the country for a number of reasons. The goal — from when I had been a fifth grader — had been to go to the US for further studies.

One reason had been to “become a thulo manche” (an important/successful/good person). Another had been to prove that someone from my socio-economic background can also perform well academically and succeed professionally. Another had been to escape the constraints and limitations of Nepali culture, society, and people. Another had been to free myself from the yoke of the Bhote label, having suffered from it from even as a small child.

Still another had been to be the first one from my village to break out of the mould and thus become a role model for children both from my community and others from backgrounds similar to mine, paving the way for them to also dream of achieving academic and professional success, something such children are told — by our society — they aren’t capable of etc.

Yet another had been to see and learn about the world and its people.

I was convinced that were I to remain in Nepal, I would struggle to accomplish any of those goals.

Apart from the reasons I have already alluded to above, I had still yet another reason to escape: severely limited social capital, colloquially referred to in the country as “source-force“ (money/wealth and connection)!

In a country ruled by nepotism, neither my family nor I had connection to, patronage of, and assistance from those in socially, economically, and politically powerful positions.

Rare had it been for someone sufficiently highly placed to make a phone call on my father’s behalf or my mother’s behalf or on behalf of any one of my relative’s or mine to help us overcome a mundane bureaucratic hurdle; forget about arranging professional employment, forget about job advancement etc. Hardly anyone in my community was highly educated and/or professional anyway.

Even those holding political office in the area we lived or were from, officers who had a mandate to help folks like my family and others in my community with bureaucratic hurdles, for example, would not readily do so. Often they would make people from my community jump a lot of hoops!

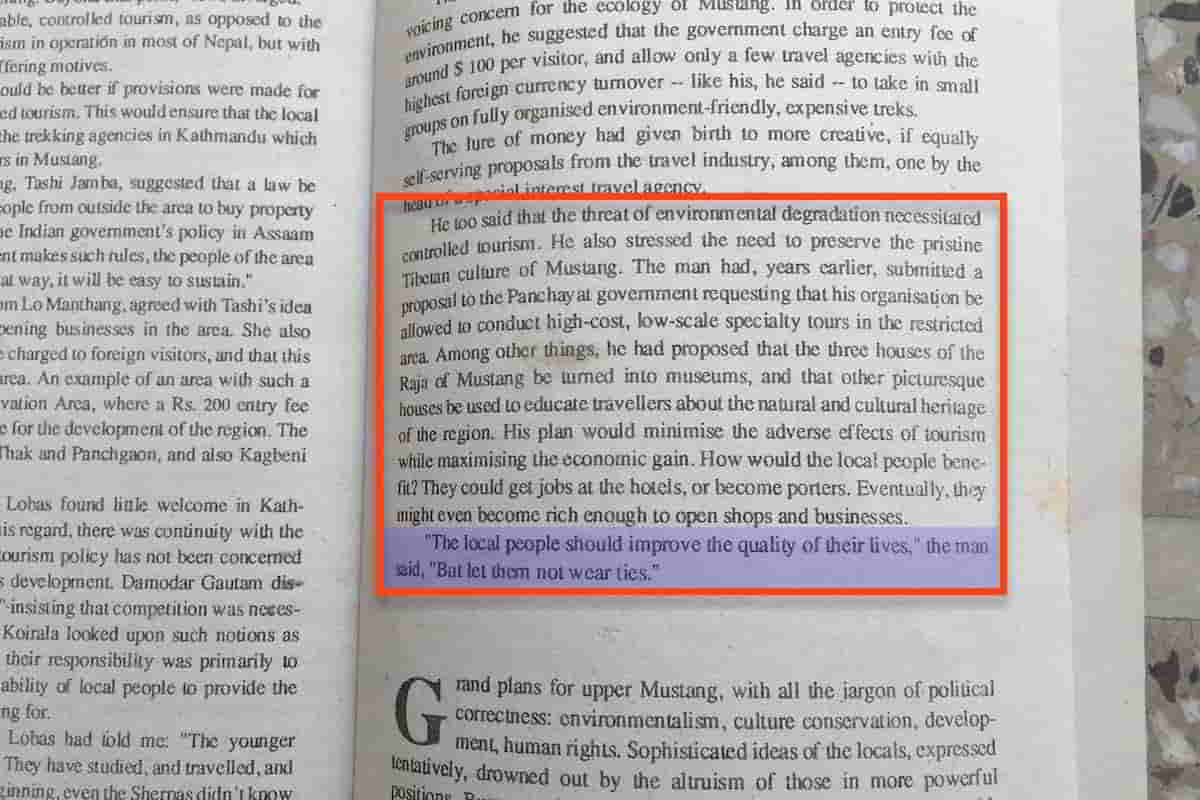

As secondary school student, I didn’t feel I had — nor grow up to have — a strong enough connection to powerful men who could or would make a difference in my life. I really didn’t feel I had anyone who could put in “a good word” on my behalf for anything. Far from “putting in a good word”, or helping me, encouraging me, and driving me to succeed etc. I believed — rightly or wrongly — the highly placed Nepalis looked down on the likes of me from Mustang. (See image at the top.)

I was pretty certain that I would struggle to “get far in life” if, staying in Nepal, I tried to do or be something different whether different from what most from my community did or were, or different from what the wider Nepali society expected the likes of me from Mustang to do or be.

Even as a young student, least I suffer from someone of higher stature “putting me in my place” — because I appeared to have forgotten my “place” for example — I had to and did display full cognizance of my taha (place/position in the highly stratified society). I had to appear to be deferential, and at time even subservient, “well-behaved”, and I had to be soft-spoken and not appear too clever or intelligent etc., especially in the presence of adults, most often men. I had to be extra-careful in my speech and manner in front — or in the presence — of men who were wealthy and/or powerful and/or of higher caste. Of course, all the while I struggled internally since I took issue with our particular culture of ass-kissing, or as we Nepali language call it chakari garnu. (One of the symbolic acts of defiance against all that was to walk with my head held high.)

What were the chances that some in the country with power and influence would actually help me in my drive to move up the social ladder in my life? I had concluded very very small!

So I did everything I could to leave the country, and did.

Ironically, leaving the country in 1988 and returning in 2013 — after spending most of my adult life abroad — I practically ensured that I would have very little social capital in the country!

#LifeEh!

What do you think?