For most of my life, both in Nepal and abroad, I had been preparing for an eventuality.

On February 12, 2013, I turned down a job offer as detailed in the first blog post in the series, The Moment of Truth I: The Offer, for just that, namely, to return to Nepal. Of course, I had a number of reasons.

One of the most – if not THE most — compelling reasons was a long-standing dream. Ever since fifth grade, I had dreamt of doing two things. The first was of going to the United States of America for studies, at the time a near-impossible dream. The second was of “serving my country” (deshko sewa garney). (Nepali education during the time of the autocratic Shah Kings made most Nepalis really patriotic.)

In pursuit of those dreams, I had done a number of things even as a student in Nepal. I worked really hard to get passage to the US for tertiary education on scholarship. (I made it via the United World College of the Adriatic (UWCAD) in Italy. The years at the UWCAD turned out to be the icing on the cake, so to speak! It would be life-changing, the experience forming the basis for my globe-trotting career of international teaching.)

They were also followed up by some very important things I did studying, living, working and traveling around the world.

Maintaining Connection to Roots

Pretty early on in my stay in the US, I realized that if I did NOT make a consistent effort to maintain my ties to the country and people, returning home at some indefinite point in the future, would be that much harder.

The two years at the UWCAD, 1988-90, I had been able to return home every summer as the college paid for my flights. That was not the case at Grinnell College in US.

So, for my first trip back to Nepal since my 1990 Fall arrival, I applied — in the Spring of 1992 — for an Off-campus Study (OCS) program. The plan had been to spend the 1993 Spring semester at Lancaster University in the UK and the following Summer in Nepal.

I had discovered that, after paying my tuition fees to the University, Grinnell College would give me directly the balance of the financial aid I was receiving from the college. With some thriftiness, I was certain I would be able to save enough to pay for a return flight from London to Kathmandu the following summer.

The college approved my application for OCS! What’s more, I did save enough and visited Nepal the Summer of 1993, my first visit in three years. The visit would mark the first of many regular visits home. I went only one more time without a visit for three years: when I was working in Malawi.

One specific reason for those visits had been to learn about the country and the people.

When visiting the country I traveled. I would also go trekking and visit places I had never been to, such as my home district of Mustang and my village as well.

Another reason had been to keep abreast of the cultural, social, political, and economic changes taking place in the country.

My third year abroad, in 1990, a revolution had toppled the authoritarian monarchy and replaced it with a democratic form of governance. More major upheavals followed. There was the civil war, the second revolution, massacre of most members of the royals family, abolishment of the monarchy and declaration of the country as a federal republic etc. The country went through dramatic changes in many areas. Not all changes were necessarily for the better though.

I made regular visits to the country to also maintain my ties and relationships with the people in the country.

Being born into the context and background I had been, I had a very limited network though. They included my school friends, my Tangbetani community members, and my family.

Yet another reason had been to keep alive the memories of my humble beginnings.

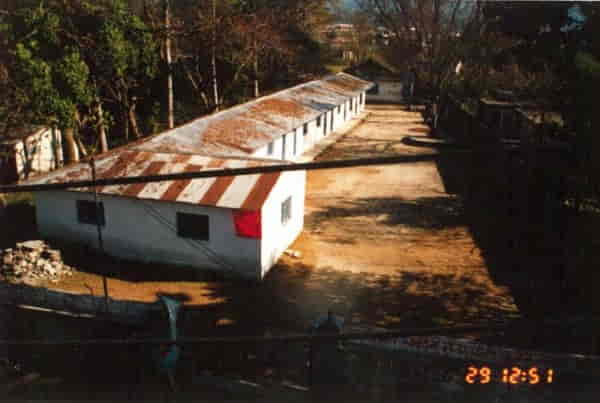

To that end, on every visit, I made an effort to visit the schools I attended in Pokhara to remind myself of where and how my incredible journey of education, and everything else that followed from it, had begun.

Opportunities turn the lives of ordinary people extraordinary!

I have always believed and maintained that I am just an ordinary person. When I would say that, it used to annoy a girlfriend of mine. She would respond saying, “Don’t say that; you are NOT ordinary! You are extraordinary!” I would add that I was lucky and had extraordinary opportunities, leading to my extraordinary life, a life I had never imagined growing up in Nepal; I am not extraordinary.

My old schools — Vindhya Basini School and Bal Jyoti School — help me remember that. They help me reinforce that, which is something I have always felt I needed and therefore actively sought out. After all, it was a teacher at Bal Jyoti School who, recognizing my potential, urged my dad to put me at a private school, changing my destiny completely!

Every single visit to the schools felt like a small pilgrimage. A pilgrimage to a place and time of innocence, purity, and even a little sacred.

(Little did I know that within about three months, during the last four days of a twelve-day incarceration in a Qatari jail for allegedly insulting Islam, I would be turned into a minor celebrity!)

Reclaiming Heritage

As a young student in Nepal and for some time during my adulthood too, “Serving my country” had a distinctly regional take.

Knowing how marginalized my people from — and how remote — my district of Mustang was, I had decided to work in the area and/or with the people. Having denied my heritage all my life in Nepal, and even struggled with cognitive dissonance, I had to reconnect with and learn about “my place,” “my people,” and reclaim “my heritage.”

Living abroad, I was finally free from the constraints of the conservative Nepali society and narrow-mined Nepali people.

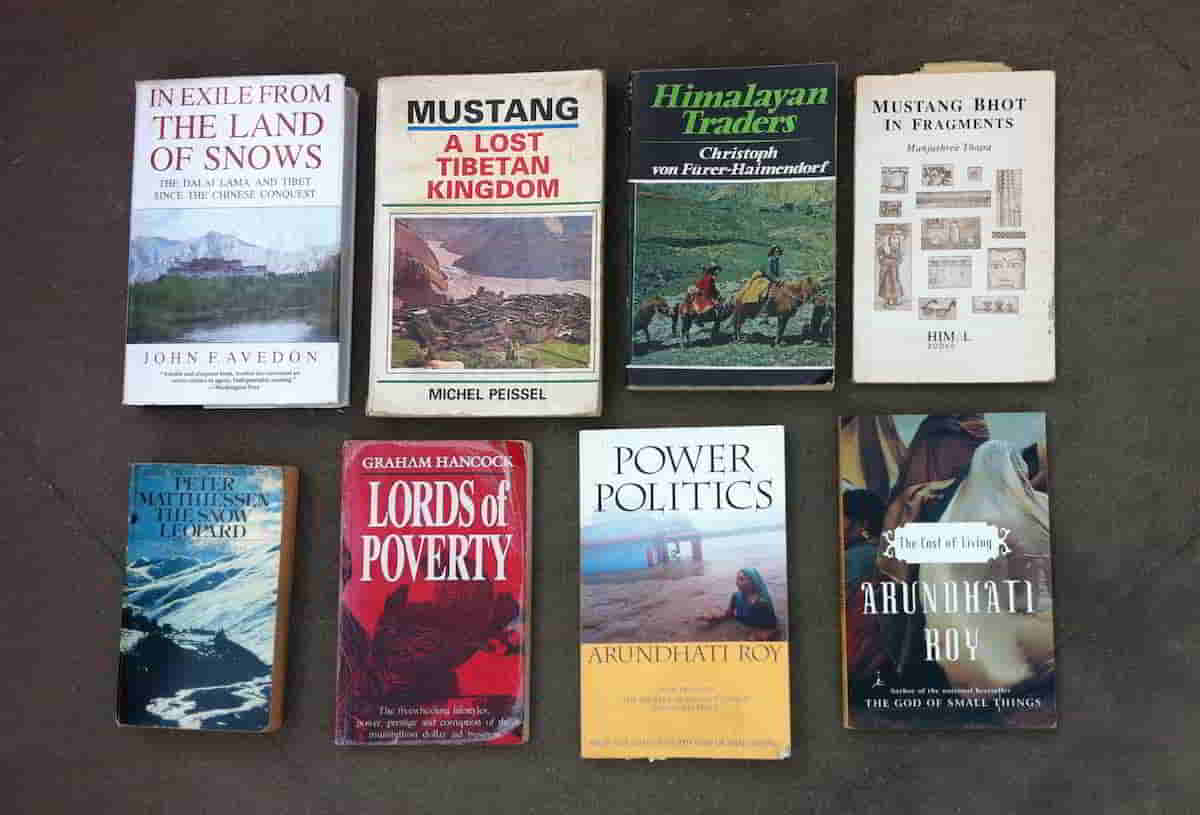

I was finally able to admit my ethnicity, display an open interest in — and an appreciation for — my heritages, and even able to take some pride in them. I read a lot about my district of Mustang, and about the history and heritage of Nepali ethnic Tibetans. Some of the early sources were John Avedon’s In Exile from the Land of Snows: The Definitive Account of the Dalai Lama and Tibet Since the Chinese Conquest, Michel Paissel’s Mustang, The Forbidden Kingdom: Exploring a Lost Himalayan Land, Christoph von Furer-Heimendorf’s Himalayan Traders, Manjushree Thapa’s Mustang Bhot in Fragments, and

I even went on a long trek of the Annapurna Circuit, in 1997, to locate the ruins of our ancestral village in Manang District where my ancestors were supposed to have come from. I also visited my village regularly, starting in 1995, about twenty years after my maternal grandfather had dropped me off in Pokhara.

By then the democratic form of government had opened up the area for tourism to generate the much-needed foreign-exchange for the country. According to Thapa — in Mustang Bhot in Fragments — all the arrangements and decisions associated with it had been a top-down imposition. The details re-affirmed the condescending and prejudiced attitudes of the elite in Katmandu towards my home district and my people.

During my early visits to the area, I discovered how visitors — both foreign and native — negatively affected the people, the culture, and the natural environment. I discovered development aid had also just made inroads into the area.

Development Aid Industry

As much as I believed that serving my country meant being involved in “development” (bikash), I wasn’t sure exactly how.

By the time I was preparing to leave for the US in 1990, I had given up on my idea of being a civil engineer and building infrastructure. I had instead settled on computer science for my major (study), recognizing the huge potential it held. No different from now with young Nepalis going abroad for studies, applying for my NOC, I defended my choice of major and its relevance to the development of the country. I don’t remember what I said or wrote though.

So, another thing I did in preparation for my eventual return was to devour development-aid literature.

One of the first books I read was Graham Hancock’s Lords of Poverty. On the back cover page, the description reads thus:

“Lords of Poverty is a case study in betrayals of a public trust. The shortcomings of aid are numerous, and serious enough to raise questions about the viability of the practice at its most fundamental levels. Hancock’s report is thorough, deeply shocking, and certain to cause critical reevaluation—of the government’s motives in giving foreign aid, and of the true needs of our intended beneficiaries.”

The book characterizes Nepal as “over-advised” and “undernourished.”

Another was Charlie Pye-Smith’s Travels in Nepal–the Sequestered Kingdom. Again, the second paragraph of the description on the page reads thus:

“The title is misleading. Yes, I wrote about my travels, but I was also much preoccupied with the way in which foreign nations were dispensing aid. The British, the Americans, the Swiss, the Australians, the Japanese – they were all there, each operating in their own separate geographical sphere. This was my first serious look at the business of foreign aid – or development assistance, as it is now politely known – and while I saw plenty of good things, much of it seemed rackety and corrupt.”

Arundati Roy’s The Cost of Living and Power Politics also had a major impact on the way my view of development-aid industry evolved.

I also learned, first-hand, a great deal about the industry during my life abroad.

The very distinct countries and areas that I lived and worked in as well as my travels in over three dozen different countries — from the Far-east to Southern Africa to Central Asia to the Indian Subcontinent — shed a great deal of light on the industry.

Even with its evolution — periodic changes in focus, in the jargon, in structure etc. — the industry was failing. I lost faith (about which I’ll have more to say in another blog post in the series).

Regardless, all these preparations had led me to the decision I made on February 12, 2013. Of course, there were a number of other pull forces from as well as push forces towards Nepal. All of them will be the subject of other blog posts in the series.

What do you think?