I have come across many Nepalis living in Nepal as well as abroad who fail to see and understand the consequences of the long history of discrimination, suppression and oppression of the people by the ruling class — the hill so-called high caste Hindus — and by the social, economic, and political structures they erected and systems they put in place.

They fail to recognize and understand some of the painful identity crisis many who don’t belong to the ruling class faced and struggled with even as a child, the way I did, for example. They struggle to understand the loss of elements of non-high caste Hindu cultures and languages as well as the loss in the diversity of cultures and languages as a consequence. They struggle to understand — or to recognize — the fact that hill High Caste Hindus enjoy structural privilege, what privilege looks like, and how structural issues the country faces now is a legacy of that history, if they don’t outright deny it.

Just earlier this month, I discovered a Xaverian friend didn’t understand what the big deal was with the creation of a federal system and the election of local representatives.

He didn’t think that there had been anything wrong with the way most of the high ranking officials in pretty much all the local government offices all over the country had been appointed in Kathmandu in the past, nor with the fact that most of them had been hill so-called high caste Hindus. Locally elected officials, really, according to him, won’t necessarily translate into economic and social developments etc. (which is besides the point). He didn’t seem to have any understanding of the concept of self-determination, for example, let alone care about it.

Another friend just the other day told me that the fault with other people not making progress actually lies with themselves. They do not work hard enough, they are not driven enough, they do not apply sufficient effort in their studies etc. to be as successful as the Brahmins/Bahuns (the highest caste).

The two friends belong to two different social circles of mine in Nepal, and from very different and distinct educational and caste backgrounds, and so are pretty exclusive. However, in the circle the former and I belong to, his opinion is shared by some others, while in the circle the latter and I belong to, his opinions is shared by most! (I would even say that the social circles each of them and I belong to are, in many ways, Nepal being Nepal, worlds of their own, which could be the subject of a few different blog posts.)

Following the toppling of the absolute monarch in 1990, the redrawn constitution recognized, for the first time in the entire history of the country, the multi-ethnic and multi-lingual population.

The constitution also showed respect for democratic values. That finally ushered in a new found freedom in the non-high caste Hindu population of the country. Little by little, emboldened and protected by the constitution, they began the process of reclaiming what they had been forced to suppress and/or deny. They asserted and expressed aspects of their identities — their language, their religions, their culture etc. — for example.

In Trident and Thunderbolt: Cultural Dynamics in Nepalese Politics, Dr. Harka Bahadur Gurung reports a number of revealing changes to the demographics of the country between 1991 and 2001.

Number of dialects/language reported, for example, jumped from 31 to 106! The increase in population declaring a language other than Nepali as mother tongue was also considerably more than Nepali, which of course is probably not explainable by just a relative increase in the population speaking those languages. Many probably felt comfortable reporting their mother tongue. Gurung notes,

“Those with Tibeto-Burman mother tongues [such as Serke, my mother tongue,] increased by one-third compared to only 21.6 per cent for those with Indo-Aryan mother tongues […]. The increase of those speaking Nepali as a mother tongue was only 18.8 per cent.”

Gurung found similar changes in religion and caste/ethnicity population in the same period, for example. According to the National Population and Housing Census 2011, 123 languages are spoken in the country, up from 106 in 2001! I would love for a comparative analysis of census data for 2001 and 2011 similar to the one Gurung did for 1991 and 2001.

During the autocratic rule of the Shah Kings, my own people, Bhotes (ethnic Tibetans) from the little village of Tangbe in Mustang District did a number of things that they felt they had to to fit in, to be accepted, and not be discriminated.

(Read My Potholed Road to UWC for more on the denotation and connotations of Bhote.) One such action they took was adopting Hindu Nepali names and surnames (Tibetan names don’t have surnames), Gurung being the most popular one.

(When I was growing up in Nepal, in the seventies and eighties, I also struggled and did what I felt I had to. Click here or here or here for more about that.)

But since 1990, things have been a little different for my community, just as it must have been for other indigenous communities.

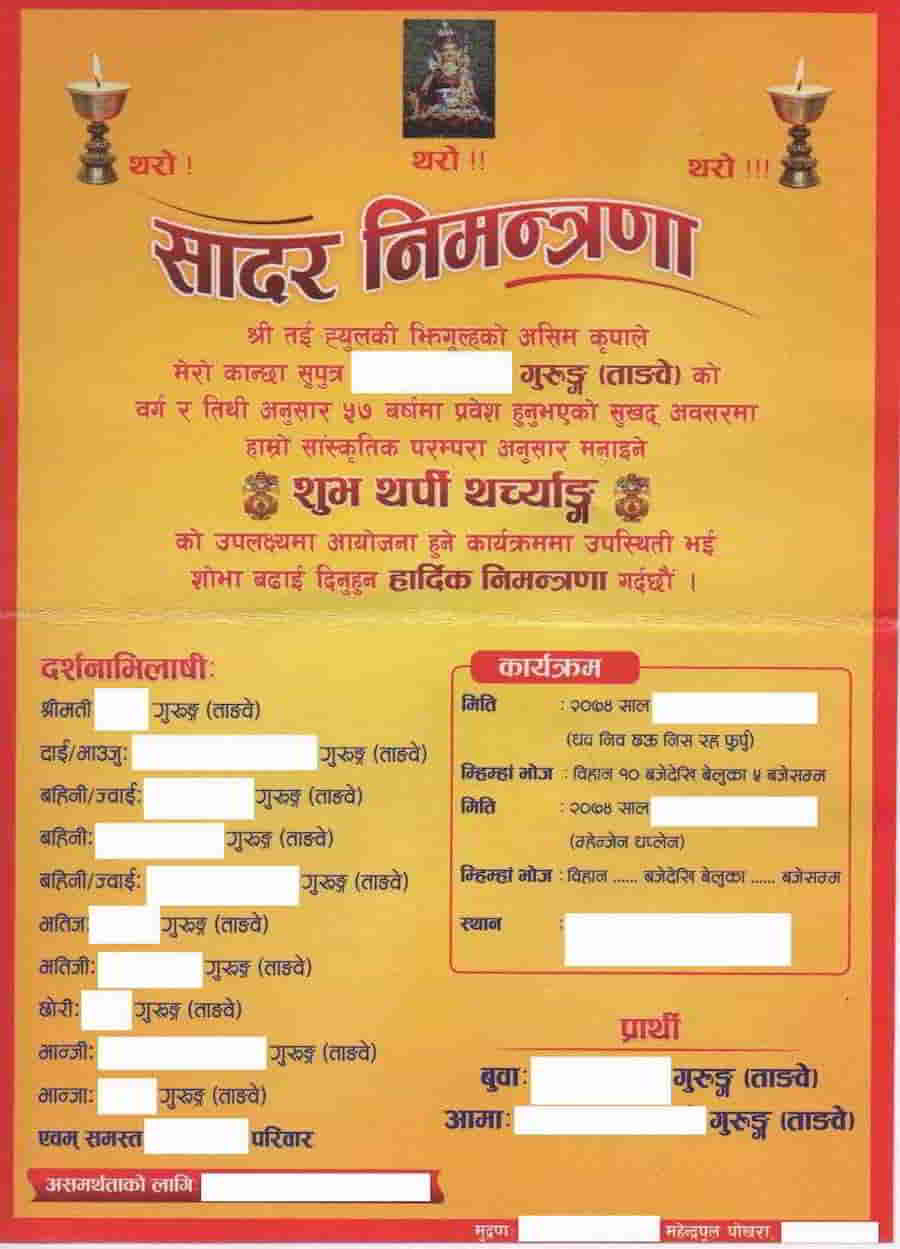

Here’s an example of how those from my community who have always been known as Gurung are now openly indicating, within brackets, that they are Tangbe, which is the name of our village.

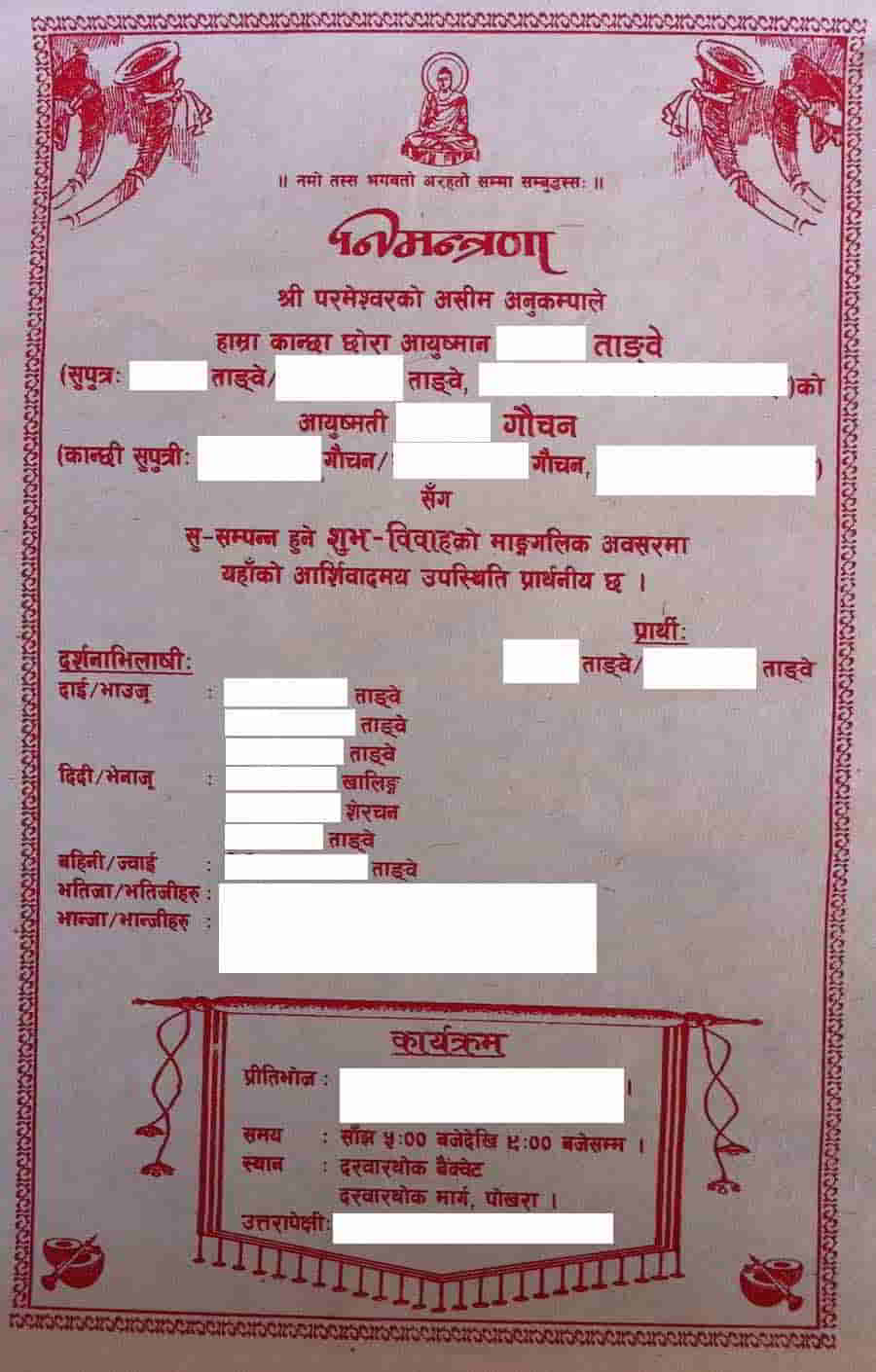

The following one, a wedding invitation to that of a young, distant relation of mine, lists Tangbe as the surname of every one of his relative from the community. Those with a different surname, obviously, belong to a different ethnic group.

Calling themselves by our village name is but only one of a number of symbolic gestures asserting their Bhote (Tibetan) identity, and proclaiming to the rest that who we are, what we are, and how we see ourselves matter.

Another is my people openly wearing our traditional costumes/attire at social functions, such as retirement celebrations, weddings etc. Still another is openly celebrating our festivals, while pretty much completely dropping the celebrations of the biggest Hindu festivals of Dassain. Many have also stopped celebrating the other very important Hindu festival, which follows Dassain: Tihar.

Returning to the wedding invitation, if you are able to read Nepali, you will have noticed that the bride is a Thakali, not someone from Tangbe. You will have also noticed that Khaling and Sherchan surnames appear in the Sister/Brother-in-law row.

While in the seventies, eighties and even the nineties, marriage between someone from my community and another Nepali was extremely rare, it has been quite common since. Among those over forty in my community, I know of only one distant cousin who, in the eighties, married outside the community (with a Gurung woman). Among those below forty, however, are many mixed couples.

Had the system of governance and the constitution not changed in 1990, were we as a community not as well off as we have been for a while now, and had my people’s access to — and level of — education and awareness not improved as much as they have, I doubt any of these changes, and more, would have been possible!

What do you think?

References

National Population and Housing Census 2011.

Dr. Harka Bahadur Gurung. Trident and Thunderbolt: Cultural Dynamics in Nepalese Politics.

Research Gate (Nov. 2015). The Ain of 1854 and after: Legal pluralism, models of society and ethnicity in Nepal. [Added on Nov. 26, 2018.]