We in Nepal suffer from a silent epidemic: mental health issues.

Any statistics you look at about the state of mind of the Nepali people is sobering. Here are two:

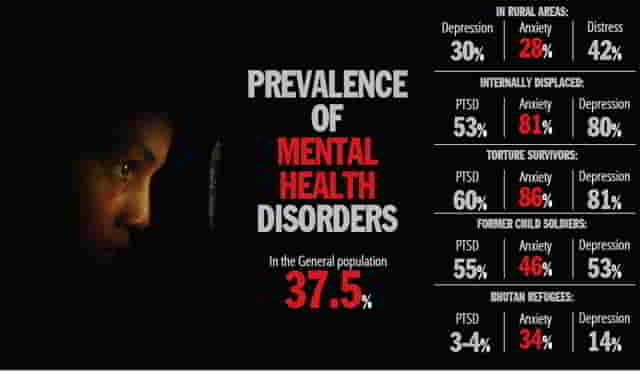

The April 7 The Kathmandu Post editorial, citing Health Research and Social Development Forum, says, “approximately 30 percent Nepalis are suffering from psychiatric problems, and over 90 percent have no access to treatment.” That’s almost one in three who suffer! In an October 2016 editorial, The Nepali Times states, “Nepalis face an epidemic of post-traumatic stress and sleep deprivation as the country copes with the aftermath of the earthquake and is tangled in endless turmoil.”

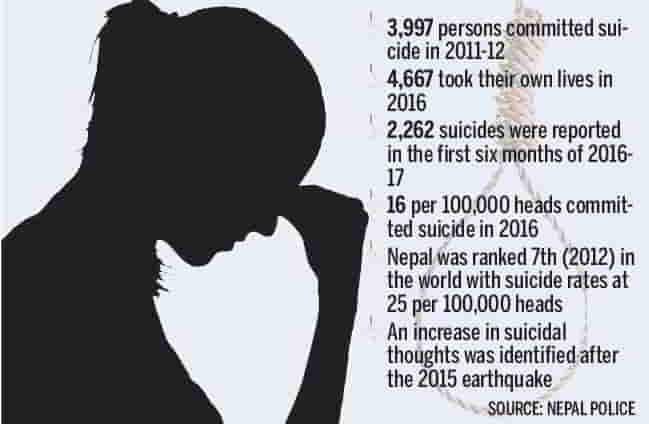

There are a number reasons for all that. There is the simple and obvious fact that we are a very very patriarchal and a conservative society which has a considerable effect on the mental health of girls and women of reproductive age. One measure of the poor state of the mental health of our females is their leading cause of death: suicide. There was the civil war the country was embroiled in between 1995 and 2005 and its aftermath. Redress provided to direct and indirect victims of atrocities committed during that time, for example, has not been anywhere near adequate. Since the biggest natural calamity to strike the country in living memory, the quakes of 2015, successive governments (and leaders) have completely failed to help the victims as well as victims of other devastating natural calamities — calamities that both preceded and followed the quakes.

More disruptions and turmoil — all man-made — have followed the quakes. Agitation in Terai that Fall, in opposition to the fast-tracked constitution, resulted in almost four dozen deaths and caused other major disruptions (such as in the education of the children in the area). It also led to the Indian government imposing an economic embargo completely disrupting life in Kathmandu Valley and elsewhere, adding to the stress and anxiety of the people.

In the area where COMMITTED works, one of the responses to the psycho-social issues faced by the victims of the earthquake was to put up a public service notice telling them to “Forget The Pain of The Earthquake, Come Together for Reconstruction!”

(Incidentally, in Nepal, psychiatric and mental issues are not seen as medical problems. What’s more, there’s considerable stigma associated with them and so open conversations about them is also taboo.)

In spite of all that, here’s what our current Prime Minister had to say, at the Columbia University World Leaders Forum on September 21, 2017, in response to a question about mental health of the Nepalese following the earthquake.

“Thank you very much…but it’s pertinent question you know. Fortunately, Nepalese people are so brave, you know, as if they are coping as if nothing happened you know. They are very brave people you know. They forget everythings [sic]. Trauma? There is no trauma…very few areas, very few people you know. They have bravely faced the situation you know.”

For more, watch the video below; it starts with the question. (The whole of the session is pretty sad, pathetic and cringe-worthy, if you want to know.)

That’s how completely out of touch and morally bankrupt our leaders are.

What do you think?

References

The Kathmandu Post (April, 2017). World Health Day: Growing suicide rates major cause for concern“

The Nepali Times (January, 2017). Stigma and silence.

The Lancet (Aug. 2016). Investment in mental health services urgently needed in Nepal.

The Kathmandu Post (April, 2017). An Unquiet Mind

The Nepali Times (Oct. 2016). The Republic of Insomnia.

Amnesty International (Feb. 2018). Amnesty International Report 2016/17. Click here for (English) online version of the report for Nepal. Click here for the complete English report for the entire world. Click here for the Nepali report. Click here for a The Himalayan Times article about the report. The report is bleak. It outlines how the government has failed the population in numerous areas, all of which, I am sure, has affected the mental health of the people. [Added on February 27, 2018]

The Asia Foundation (April 19, 2017). Dalits Left Behind as Nepal Slowly Recovers. “Researchers founds cases where high caste people allowed landless Dalits to build shelters on their land. In the early post-earthquake period, low caste people were much more likely to have received aid than others (64% versus 39% of high caste people). Concerted efforts by aid providers to ensure that Dalits and other low castes received support, strong community norms around distributing aid equally, and a sense of solidarity among the earthquake-affected that crossed identity lines combined to help low caste people cope in the immediate aftermath of the disasters.” […] “One-and-a-half years after the earthquakes, 82 percent of low caste people whose houses were impacted said they had yet to start rebuilding, compared to 71 percent of high castes.” […] “And they were almost 50 percent more likely to say a family member continued to suffer from trauma than other groups.” [Emphasis mine.][…] “The second and third rounds of IRM identified two worrying trends. First, over time low caste groups have become increasingly less likely to receive aid compared to others.” [Added on March 19, 2018.]

Annapurna (May 8, 2018). मानसिक बिरामीलाई ‘ग्यास्ट्रिक’ को आैषधि (“Gastric” Medicine for Patient Having Mental Issues). Has some additional data. [Added on May 8, 2018.]