I used to really feel uncomfortable introducing myself as “Dorje Gurung” to fellow Nepalis as a young student growing up in Nepal in the eighties.

I still do…but for the exact opposite reason!

Being born an ethnic Tibetan (Bhote in Nepali) to a poor family — with zero education history — in a Hindu kingdom, governed by an absolute monarch, who, supposedly the reincarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, pushed to further and promote the hegemony of the hill so-called high caste Hindus as encapsulated in the national slogan “ek bhasa (one language, namely Nepali, the mother tongue of the high castes), ek vesh (one uniform, namely daura suruwal, that of the high caste men), ek desh (one country, ruled — socially, economically and politically — by also the hill so-called high caste Hindu men),” and was backed by a very blatantly and flagrantly discriminatory law written in 1854 (amended for the first time in 1963 and then in 1990 but hardly ever implemented/enforced)…meant suffering from a number of issues growing up.

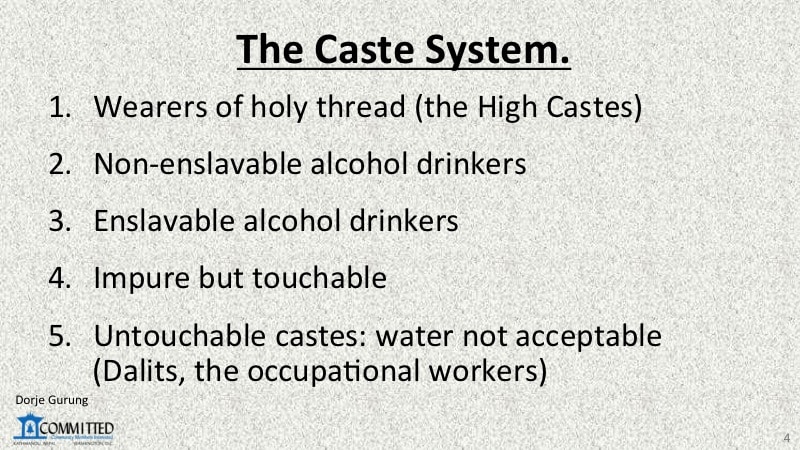

The law classified Nepali citizens into five jaats (Castes). Penned by the high castes (Brahmins/Bahuns and Chhetris, the priestly and warrior castes respectively, i.e. the ruling class), they placed themselves at the top and the rest below them, three of whom were enslavable (by them)!

Being born a Bhote, a Tibetan-Buddhist (non-Hindu), I, like the rest of the people from my village in (Upper) Mustang District, belonged to (3) one of the lower enslavable castes.

To avoid being discriminated against though, my parents’ generation did a number of things to pass for something other than a Bhote. One of those was to adopt for themselves — and give their children — Nepali (distinct from Tibetan) names and Nepali surnames. (Surnames/family names don’t exist in Tibetan names.)

Most chose “Gurung” for a surname. (Surnames in Nepali denote a people. The Gurungs are a people indigenous to mostly the areas around the city of Pokhara. They belong to the “Non-enslavable alchohol drinkers” caste!)

Discrimination faced by the people in Nepal based on one’s heritage was — and still is — not limited to the Bhotes.

I have been told that also Tamangs, a Tibeto-Burman people, for instance, faced similar issues, leading them to also adopt surnames such as Gurrung, Rai and Limbu etc. While the latter three could enlist in the British Army, for instance, Tamangs were barred from doing so by the Rana rulers so that they could be used virtually as slaves! Dalits also modified their surnames to also avoid being recognized and discriminated. I have been told that low-caste Newars also did the same. Madhesis, Nepalis indigenous to the Southern Plains, are another people who have faced and continue to face incredible amount of discrimination. Click here or here for blog post containing examples, or here for a page listing blog posts about Madhes (the Southern Plains).

Worse still are the stigma associated with low-caste birth and the taboo surrounding open and honest conversations, discussions and debates about the social construct and ill that the caste system is.

At no time during my years as a student at St. Xavier’s was there any platform or open forum or conference or opportunity in the classroom of any kind for us students to talk about the system.

Forget about during my schools days, even throughout my adulthood and even as a middle-aged man, I have rarely been able to engage adults, in person, in Kathmandu, on conversations about the system. (What I have had, have been limited to posts and exchanges on social media (click here and here for two examples) and presentations at schools.)

I don’t recall having any conversation about the system at any of the social gatherings of my classmates I have attended in Nepal since graduating in 1987. And we have had many many gatherings. Most of my classmates have advanced degrees and/or are accomplished professionals with years and years of experience in their fields, or are mostly successful in their jobs and lead mostly comfortable lives etc.

What is the likelihood of a conversation on the topic with them in the future? Unfortunately, I think, zero! The only classmates I have had conversations with on the topic, in private, have been Jayjeev, my colleague at COMMITTED, during our visits to Thangpalkot, and other close classmates ALL of whom live abroad.

Anyway, returning to my name, when I was admitted to St. Xavier’s Godavari School, my father dropped my Nepali (Hindu) name and, instead, combined my Tibetan name and Gurung to come up with my new name.

While I grew up ready to challenge anyone who might question my ethnicity by saying, as per my father’s instructions, that I was a “Ghale Gurung,” I had also been acutely aware of the fact that I had a Tibetan (Bhote) first name!

Of course, I pretended to be a Gurung. I did everything I could to hide my Tibetan heritage (for example, by losing my Bhote accent among others), to appear to be someone other than a Bhote because of all the negative connotations associated with being one and feeling embarrassed and shameful for my accidental birth-ethnicity, something Nepali society had taught (forced?) me to feel.

But, I was pretty certain that more or less every Nepali could tell that I was a Bhote just from my facial features. Those who couldn’t, I was convinced, would be able from my first name!

So, I often felt embarrassed and uncomfortable introducing myself to fellow Nepalis.

Apart from the discomfort I felt arising from divulging my identity as a Bhote, what made the process doubly discomforting was that it forced me to internally wrestle with the harsh reminder of the fact that I lived in denial of my heritage.

Luckily for me though, I had the privilege of attending the UWC of the Adriatic in Italy from 1988 to 1990, which initiated a process of earnestly questioning myself about my self, my identity, my country, our culture, our society etc.

Living and studying among 200 students representing 65 or so different countries, that was to be expected. Besides, one of the reasons I had wanted to “escape” from Nepal had been to set myself free from the various constraints imposed on me by the predominantly Hindu-Nepali culture, systems and people.

Bit by bit, the discomfort was replaced by an expanded idea of — and sense for — my identity and self accompanied by a sense of pride in my Tibetan heritage, when the two years in Italy were followed by four in the US.

I took an active interest in and began keenly learning about my culture, our traditions, our spirituality and religion, and our history etc. and also sharing them with others. While a study-abroad student at Lancaster University in the UK, I studied Buddhism. I began visiting Mustang and my village whenever I could during my regular visits to Nepal! In 1994-95, I ran a weekly activity on and gave a presentation about Buddhism at the UWC of the Adriatic. In 1996-97, I gave presentations on Mustang and Tibet at Red Cross Nordic UWC in Norway. (Click here, here and here for a reproduction of the texts of the presentation on Mustang.) In the Summer of 2007, I did something I had had in my bucket list for a long time: I visited Tibet.

Little by little, I learned that I had been born into a people with a very very rich culture, an incredible spirituality and a long and illustrious history among many other things!

With all that knowledge and understanding about my people and my own self came awareness, which in turn was accompanied, naturally, by changes in my attitudes and behaviors.

One of the first things I did, some time after graduating from Grinnell College in 1994, was to give away my Nepali national dress (daura suruwal) and opt to wear, in its place, the traditional Tibetan dress called chuba (Kohn in Serke, my other mother tongue) when I was called on to represent Nepal. Growing up in Nepal, I wouldn’t even have been seen dead wearing the attire!

A chuba, I had come to realize, represented as much Nepal as did a daura suruwal; that a dhoti (attire of those indigenous to the Southern Plains) represented as much Nepal as did a daura suruwal etc.

Also in the mid-nineties, when I created my first web-based email address (on Yahoo.com), for a username, I used what I believed at the time to be the best transcription of my full Tibetan name.

I also started wearing Tibetan holy threads and amulets around my neck (see image below), in a way that was visible to others. Growing up in Nepal, when given them, either I would not wear them at all or, when I did, I would hide them under layers of garments.

I started talking to my Xaverian classmates about my heritage whenever questions related to it came up. Once, also in the nineties, I even invited a close classmate of mine to a Tibetan-Buddhist religious function at our home. But that, as far as I can remember, would be the first and the last time I would invite, as an adult, a Xaverian classmate to my home.

When I would be in Nepal for visits, I started speaking Serke in public without feeling any shame or discomfort etc. etc. etc.

But, from the nineties to even today, the discomfort with introducing myself to fellow Nepali has remained.

The source this time? My surname.

In other words, with my pretending to be a Gurung! To be sure, this discomfort has never had anything to do with my having something against the surname specifically or the people it represented. Never!

Rather, it had to do with the fact that I no longer felt uncomfortable with my Tibetan heritage! It’s been a long time now that I have had absolutely no issues with being recognized as a Bhote. As a matter of fact, I WANT to be recognized as one!

(That however is NOT to say that I don’t mind non-Bhotes calling me a Bhote, the way someone, who I probably know, did back in March 2015 on Facebook. I do! It is after all an ethnic slur. It’s one thing for a Bhote to call himself/herself a Bhote, or Bhotes to call each other Bhote, but quite another for a non-Bhote to do so, which however could be a whole different blog post all together.)

At about the same time, the nineties that is, I suspect the renaissance of sorts with different peoples of the country asserting — and expressing pride in — their ethnic identities in different ways began. (A popular revolt had toppled the absolute monarch ushering in a democratic form of government in 1990.) One of the ways was probably reverting to using surnames which reflected what they called themselves in their own language.

It’s now quite common to find Tamangs using Shangbo, Thing, Gole etc. among others, for their surname, instead of the generic one, namely Tamang. Others who have done something similar are the Rais (e.g. Bantava), the Limbus (e.g. Shotemba, Palungwa) and the Gurungs (e.g. Tamu).

What I myself have done for a long time is to introduce myself to fellow Nepalis thus: “My name is Dorje Gurung, but, I am NOT a Gurung; I am a Bhote from (Upper) Mustang.”

That actually has gotten tedious. There are times when I introduce myself as just “Dorje” and leave it at that. What I really really want, however, is to NOT have to do either.

For a long time, I have been contemplating either reverting back to my original Tibetan-buddhist-monk given full Tibetan name or replacing Gurung with the surname many in my village have settled on: Tangbetani (literally, “someone from Tangbe”)! The reason is NOT just becuase I don’t feel comfortable with my surname and I want my name to reflect my heritage and my identity etc., as I have amply made clear, but also because I don’t want to pass my adopted surname to my posterity, if and when I have them!

However, recognizing that changing my name will be a major undertaking given the kind of life I have had — education in five different countries, work experiences in ten etc. etc. etc. — I have avoided really looking into how I would have to go about it.

I may have just found a solution though!

I was talking to a distant relative last week, over the recently-concluded Dassain Festival break. He suggested I get an official paper which says that I have two names: my official name and my original Tibetan name. That way I can continue to be officially Dorje Gurung but can introduce myself with my Tibetan name, completely avoiding having to BOTH introduce myself as “Dorje Gurung” with the qualifier (or just “Dorje”) and pass the Gurung surname to my yet-to-be-born children!

Incidentally, when it comes to my identity, my surname is not the only thing that’s fake. My birth date is as well, but that could be a whole different blog post on its own!

What do you think? Do you have a similar story to share?

References:

- Macfarlane, A. A guide to the Gurungs.

- The Kathmandu Post (July 2015). The country is yours. “Tamangs were prohibited from accessing the main form of social mobility available to the major Janajati groups—service in the British Indian army. All because they were required by the Kathmandu elite[.]”

- The Record (April, 2019). Lying to survive: Dalits in urban life. [Added on Feb. 16, 2020.]

It;s fine if you still use the surname as Gurung cause even we migrated from Tibet Our Phayul, i know that the Nepal Government is really racist asf.

btw, i am a pure blooded Gurung from Sikkim.

I did not bring daura suruwal when I came to the US for college. I brought the traditional attire of my ethnic group (Gurung) and wore it during the cultural show of new international students. There were other Nepalese students (Newar, Magar, Chhetri) who had already been studying there and none of them asked me why I did not wear daura suruwal (they had brought ‘national dress’ from Nepal for their freshman orientations the previous years). The following year, a Bahun(Brahmin) freshman wore daura suruwal at the cultural show of new international students. After seeing pictures of my freshman year’s cultural show on facebook, he asked me in a rather confrontational tone why I had not worn daura suruwal, the national dress. I explained to him that Nepal is a diverse country and different ethnic groups wear different attires and all those attires represent Nepal. But he was adamant that we should wear one dress outside of Nepal. I told him that by wearing my own traditional attire I was showcasing the diversity of Nepal which many people were unaware of because pretty much everyone wore daura suruwal at such programs (it was mid 2000s, I suspect it has changed much now). In the end, I told him that daura suruwal was his attire and I had no objections to him wearing it and in the same way he should not have any objections to me wearing attire of my own ethnic group. Over the years, I have found that despite their American education many Khas Nepalese hold chauvinistic views and long for the Panchayat era government ideals of ek bhasa, ek vesh, ek desh.

I am well aware of people adopting (or having to adopt) others’ surnames in Nepal (not sure if you have seen it: http://nepalitimes.com/news.php?id=17040#.WfagH2hSzIU). People adopted Hindu names and practices for many of the same reasons you have mentioned about your father adopting the Gurung surname. The Shah Kings faked their genealogy to show that they came from illustrious Rajput royal lineages in India. The Ranas dropped Kunwar and adoped Rana surname, and also had the king approved a similar fake genealogy. But unlike commoners who adopted others’ surnames to escape discrimination, the Shahs and the Ranas did it to increase their prestige.

Dear TG,

Given that it was his first year at college (and possibly in the West) the propaganda he grew up with in Nepal must still have had a sway in how he thought of the country and fellow citizens. But I am not surprised when you say “despite their American education many Khas Nepalese hold chouvanisti views.” I have engaged with middle-aged men educated abroad who still have similar mentality to your Bahun freshmen. I have engaged with some who display a complete lack of knowledge and understanding of the history of our country — the real history, NOT the history we were taught in schools. That is NOT to say that ALL high castes are the same. I have high caste friends who are completely open-minded, aware of our history etc. and recognize the multi-cultural and multi-enthnic make-up of our country, and know and understand that to be an asset! (I have written about that here: http://www.dorjegurung.com/blog/2015/11/there-is-poor-representation-and-then-there-is-nepal/) Annyway…

Good on you for acting on your beliefs about your identity. Just because you choose to emphasize your Gurung identity does NOT mean you value your Nepali nationality any less!! Such arguments are made by people who themselves are insecure about their own identity and nationality!

And to answer your question about whether I had seen the article in the Nepali Times, yes I have. I even contemplated sharing a link to it in the reference section but ended up not doing so.

As for the royals doing what they did to increase their prestige…you will probably not be surprised to learn what the royal family of Mustang has for a surname: Bista! Yes, the Nepali/Hindu (Khas-arya) surname of Bista!

To us you’ll always be Dorje, without the ethnicity or caste baggage. You are who you are…

I didn’t know this background, Dorje! I did remember from eons ago that your birthday is made up. Thanks for a fascinating post and please tell what your Tibetan name is ( or did I miss that?) Tamang?

You are welcome Vicky! I had fun writing it!

As for my Tibetan name, I left that out deliberately (just as I did my Nepali name). I didn’t want to reveal too much! But, if I have sent you emails from my yahoo.com account, you would know my Tibetan name. (Incidentally, Tamang is actually a Tibeto-Burman people. They are scattered in the hills East, North and West of Kathmandu valley.)