If you are a member of the majority in a country, it’s only natural to think, believe and act in the way the majority do because they constitute “the mainstream.”

In the US, that means being white and middle class. That is also the case in Europe and the rest of the Western world. In the Gulf, it’s being a Muslim and everything else that entails, though of course there are differences between the countries in the area based on geography among others. In India, it’s being a Hindu, while in Pakistan and Bangladesh it’s being a Muslim. In Mexico and the Philippines it’s being Catholic, among other things.

A majority of the population of Nepal are Hindus and therefore the culture and traditions of (hill so-called high caste) Hindus constitute “the mainstream.”

What’s more, during those decades I was growing up in Nepal, an absolute Hindu monarch, i.e. a dictator, who suppressed non-Khas-arya peoples, cultures, and languages, ruled the country. So, in the seventies and eighties, most in the country naturally assumed that everyone followed and celebrated Hindu festivals, for example. Furthermore, also naturally, the non-Hindus felt compelled to show that they actually did belong to the mainstream and were patriotic citizens, 100% behind and fully supportive of the King and his cronys.

Children from non-Hindu families, like my friends and I from Tangbe, Mustang, therefore grew up with their families “embracing” some of the mainstream culture, attitudes and practices.

One such practice was “celebrating” (the recently concluded) Dassain and Tihar (also known as Dipawali/Diwali, the Festival of Lights), the two most important Hindu festivals and — because of that — the national festivals of the country.

One reason, obviously, again, was to show that they and their children supported the King and the country’s ruling elite. Another was probably to avoid being recognized and discriminated as (low-caste) Bhote. Yet another was probably to make sure that their children, my generation, didn’t feel left out and didn’t get mocked and picked on by our peers.

Another reason still my parents’ generation also “celebrated” the festivals was probably to ensure that their children would grow up competent in — and with a sense of belonging to — the mainstream culture of the country and the wider society.

So, there were times when my family had Tika on Dassain as well as carrying out Bhai Tika (Brother’s Day) during Tihar.

There were even times when we, the children, received gifts of money and a new set of clothes and went out gambling with the neighborhood children, betting money on the traditional street-side game of Jhanda Burja (Flag Crown). (See image at the top.)

After leaving Nepal (in 1988), the value of those celebrations dropped steadily.

My generation of Tangbetanis (ethnic Tibetans from the village of Tangbe, Mustang), even those living in Nepal, learned and realised why our parents had done what they had done, when they had done them.

For me, everything would come full circle in the nineties.

After everything our parents’ generation had done to help us reject and deny our heritage, and having contributed to it as a student growing up in the country, as an adult, feeling the uselessness of continuing any of that charade, I would come to embrace and assert my non-Khas-arya cultural, linguistic and ethnic heritage.

Dassain and Tihar was another of the many casualties of the decision: I stopped celebrating them!

What I have done instead during the Holidays is travel! Last year’s Dassain road-trip saw me braving the out-of-control traffic and horrendous roads and highways West and South-West of Kathmandu while enjoying visits to interesting and beautiful places along the way. Tihar took me to Pokhara, the most beautiful city on the planet, and to Maya Universe Academy, a school in Tanahu, founded and run by a fellow Nepali UWCer.

This past Dassain, earlier this month, I did a short trek with my cousins wondering if my still-recovering left-foot would hold out! It did and I had a great time.

The Holiday, which began with a drive to Pokhara, had a rough start though.

Though just 200 km West, it took us more than 9 hours in the car! Involving two stops totalling about 3 hours (one for tea and another for lunch), door-to-door the journey lasted 12 hours!

Here’s what partly kept us on the highway one of the two times we were stuck in traffic.

In Pokhara, I saw a familiar sight that I hadn’t seen in a long time, bringing back long-lost memories: high altitude sheep and goats!

Growing up in Pokhara until our move to Kathmandu in 1985, one of the things I always associated with Dassain were the two animals that descended into the city. Part of the reason was also that, for at least a few years, my father brought them into the city. The mountain goats and sheep raised in Mustang were herded into the city on foot. Apparently, dozens would disappear in between, many trapped and stolen by locals along the way.

Dassain tradition calls for the sacrifice of the animals to the Goddess Durga on one of the latter days of the multi-day festival.

While, as a people, we the ethnic Tibetans from Tangbe, Mustang, didn’t really engage in that aspect of the festival, in Pokhara, extended families would get together in one of the relative’s houses, butcher a goat or a sheep and have a feast!

The best part of the feast for me was always the unusual body-part delicacies!

Delicacies such as barbecued heart and tongue directly on the coals, raw liver with chilly-pepper mix and the brain have always been favorites of mine! Sausages, an item invariably made and served during such a feast, is another one that I loved and still do!

To this day, our home-made sausages — using intestine for casing, the fresh raw meat from different parts of the body, blood for the base, lots of spices and the stomach, which itself is a delicacy when boiled afterwards and used as a funnel when making a particular sausage — are the best!

It’s better than the Hungarian sausage my good friend Zsolt introduced me to at the United World College of Adriatic. We used to have it at our special weekend-breakfasts! It’s better than even Chorizo; better than the Spanish blood sausage; better than black pudding, the European version of blood sausage — all of which I have had!

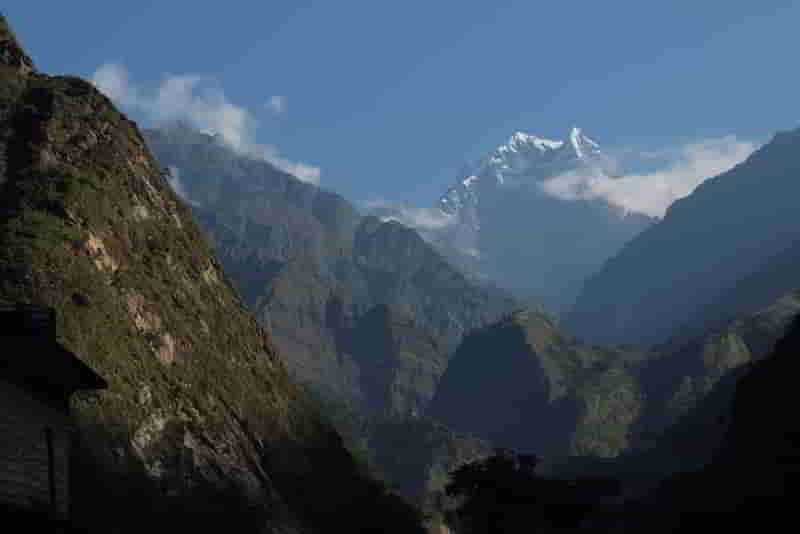

From Pokhara, we ventured into Annapurna Sanctuary for a trek to Tatopani, via Ulleri and Gorepani.

After lunch between Birethanti and Tirkhedhunga, we headed up towards Ulleri. Somewhere before Tirkhedhunga, I came across a family that had butchered a goat or sheep at home the way our families did in Pokhara!

While we, my group of friends and cousins on the trail, did NOT sacrifice any animal to any Goddess, we picked our own local chickens for a number of our meals.

After spending a night in Ulleri, we headed to Gorepani. This time, I came across a church on the way that I don’t remember seeing the last time I was on this trail, which had been in the Fall of 2013.

On the trail, of course, the views of the mountains were spectacular, like always!

In Tatopani, I spent parts of an afternoon and a morning helping Sukriya Begham with her English homework.

Being the teacher that I am, seeing her working on it and noticing how she had made a number of mistakes, I couldn’t avoid sitting down next to her and helping her.

From the (tailoring) business her mother was engaged in, I assumed her family to be a Dalit. Her surname told me that her family may either have converted to Islam at some point, or they have always been Muslims. But because they live in a largely Hindu country, they may have struggled to move out of their hereditary profession.

I didn’t want to make her or any member of her family uncomfortable so I didn’t ask them any questions about their religion and profession.

It’s not just that I and many of my generation of Tangbetanis don’t really celebrate Dassain and Tihar, my whole family doesn’t any more.

With the introduction of a democratic form of governance in 1990, more and more of the citizens of the country have reclaimed and reasserted their identities as well as their linguistic, cultural and religious heritages. We at home no longer feel compelled to endorse the (Hindu) mainstream culture and practices, and that’s why we don’t.

My little nephew will grow up without any sense of shame about his Tibetan heritage. Sure, at his school, the Hindu festivals and religious days are mostly celebrated, as is to be expected, though it wouldn’t take too much effort on the part of the school and teachers to be a little more inclusive. (That however could be the subject of a whole different blog post.)

However, I have volunteered to read to his class and when I do get invited — I have been assured that I will be invited — I’ll be sure to read books that talk about other cultures, religions and people in the country!

Interestingly, though born a Tibetan Buddhist and I grew up in a predominantly Hindu Kingdom attending a Jesuit school, where NO proselytizing took place at the time, I have celebrated Christmas more than any other religious festival!