The tears that flowed liberally the afternoon of May 13, 2013 for a long time on the Doha-Kathmandu flight, would become — after the flight landed — a regular, but secret, companion of mine.

In the flight itself, those tears had been of relief, hurt, anger and rage. After all, I was leaving behind a place where, during my short tenure as a teacher at Qatar Academy, students and parents had treated me so badly that I had been driven to the bottom, personally and professionally. I was leaving a place where few of those same people had me fired from my job — causing me to lose thousands of dollars — and had me incarcerated for allegedly insulting Islam. I was also leaving having just won my freedom from a place where I had experienced the depths of despair coming, as I had, face-to-face with the potential to losing EVERYTHING, including my sanity. I was leaving a place where I had major issues with the routine inhumane treatment of fellow Nepalese, other Asians, and Africans.

In Kathmandu however, initially at least, the memories of “Chotu,” a cellmate, triggered the tears.

The heart-wrenching and unjust story of the boy had made me sob uncontrollably for the first time the afternoon of May 12 in Doha, in front of my friends and colleagues. Little did I know that firstly, that would be just the first of many MANY more to come, and secondly, that would be the last time I would shed them in public.

Short in stature and very childlike in speech and mannerism, Pawan Kumar Kurmi is Chotu’s real name. I remember him telling me that he was from Dang but information I got later says that he is from Banke district in the Mid-Western plains of Nepal.

Fate had dealt him a cruel hand (excuse the pun).

He had been born a Dalit, an untouchable, the lowest caste in the Nepalese caste system and so a member of the most discriminated and marginalized people in the country.

As if that hadn’t been bad enough, he had a congenital hand deformity: syndactyly. He had been born with the last three fingers in both his hands fused together (see image at the top).

In one of my early conversations with him, I had asked about that, in Hindi. (Chotu didn’t speak Nepali.)

“Aap ke pariwar ne kyew operation nai karwayi jab aap batchhe they?” (Why didn’t your family have your fingers operated on when you were a child?)

I still remember his matter-of-fact response: “Hamare pariwar me to eghara kuch aur log hai jo aaise hi janam huwa.” (We have 11 others in our extended family who were also born with this.)

Meaning no one had done anything about those born before him with the congenital anomaly! And naturally, his family hadn’t thought of doing anything about his when he had come along. As a Dalit family, I suspect a combination of poverty, lack of medical facilities in the area, and viewing it as fate, prevented his family from even contemplating consultation with medical professionals about correctional-surgery options.

The cruelest of all was being falsely accused, as a minor, of the murder of a fellow construction worker.

Falling sick on the job, Chotu and other fellow workers had checked the “victim” into a hospital. He had died two days later.

There was an innocence and naïveté about Chotu that was hard to miss. When he recounted his story, it was as if like he were re-telling the story of a character in a movie: he relayed it in a completely detached way, for instance. Rounding off his story of how he had ended up in jail about three months before I arrived on the scene, he told me, “Mujhe pata nahi wo kaise mara.” (I don’t know how he [the victim] died.)

After all, he was just a kid, like many I had taught in my teaching career.

Back in Nepal, in the days and weeks following that May 12 afternoon, Chotu would come to symbolize the unjust, careless and brutal Qatari legal system on the one hand, and the suffering of the Nepalese migrant laborers in the Gulf — and their families in Nepal — on the other.

Any time I talked about my Qatar ordeal and those of others, his story would be at the forefront. And when sharing it, I would struggle to keep myself from breaking down.

One of those times, I was speaking to a group of BBC Action staff one afternoon in June. Reproduced below (verbatim with all the mistakes) is Shristi Rajbhandari’s description of that moment in her blog post about the meeting.

“As he was murmuring, for a moment there was a pin drop silence in the hall room, he controlled himself before he broke into tears as he began to share the story of a 19 year old Nepal boy, who is still in the custody without any awareness of what offence he had committed.”

Once, on June 20 to be precise, when I was reminded of him by a song, I even gave into the temptation of posting it on Facebook, but left out the details about the tears.

Strangely enough, I discovered music — two songs in particular — also triggered the tears.

The first one, Humse Ka Bhool Huyi (What Did I Do So Wrong), is from a 1979 Bollywood movie: Janta Hawaldhar.

My memory associated with the song has nothing to do with Chotu or Qatar. The memory, in fact, takes me back to the winter of 1982-83 in Kalimpong, India, where I watched the movie. Ever since then, feeling that it spoke to me about my personal life — struggling as I was with some aspects of it — I have always loved the song.

The second music-trigger was Kenny G’s Going Home.

For a long time, before I returned to Nepal for good in May, the music had always encapsulated the conflicting emotions entailed in that eventuality. Namely, the longing I had for the country and the people, one steeped in some idealized version of them, while, paradoxically, aware that they could disappoint me, because, so much will have changed by then, including my self.

When either of these two songs would come on — on my music system or in the car driving — and I was alone, I would be reminded of Chotu…of his voice, his easy smiles and laughter, and his hands. Then I would be overcome with emotions and start tearing up!

With Humse Ka Bhool Huyi, I have reasoned that maybe I empathized so much for the boy that the lyrics captured the predicament he was in as well as his cries! So, my own tears were me crying for him, crying in his place, for his predicament, for his freedom. The first two lines of the song, after all, does go like this:

Humse ka bhool huyi, jo ye saja humka mili /Ab charo hee taraf bhandha hai duniya ki gali

(What did I do so wrong that I am being punished so / And now all the doors are closed to me)

With Going Home, maybe the realization that Chotu might never get the opportunity to return home was making me cry. Or maybe I cried because of a young life pretty much “snuffed,” because of opportunities lost, and the cruelty in that. Furthermore, this may sound patronizing but the feeling that — being so young — he might not have fathomed the enormity of his loss may also have brought on the tears!

In time, I discovered other triggers too, such as Images and/or stories of suffering on TV, on papers, and even on the streets of Kathmandu and elsewhere etc.

My bleeding heart had turned into one hyper-sensitive to suffering…of others. I regularly pondered over the inadequate support migrant laborers in Qatar, and elsewhere in the Gulf, received. I reflected regularly on the suffering and cries of those in Qatar — their cries for freedom from their predicament and despair, their cries at their misfortunes, their cries at their mistreatment etc. — and their fruitlessness. I also reflected regularly on the plight of their families in Nepal, whose cries also went unnoticed, un-soothed and unanswered, mostly. In time, I guess what must have happened was that I started seeing their pain and suffering in other Nepalese I came across — in the media and elsewhere — and even reacting to them.

The last of the triggers wasn’t even really a trigger: it consisted of just being a little inebriated and alone!

When inebriated, not surprisingly, those issues, concerns, thoughts and images of suffering would flood my head. Invariably, an overwhelming feeling of inadequacy of the work I was doing to try to address them would overcome me and the tears would follow.

I did try to do what I could to help those left behind…to stem the flow of those tears.

I contacted people working on migrant right issues. I shared information with them — information I had gathered while in jail and information I had received since returning to Nepal. We discussed possible ways we could help them etc. I did the same with anyone and everyone contacting me expressing an interest in helping them.

I was also in touch with friends in Doha who offered to help. One of those friends, going to great lengths, secured Bishwas’ release. (He was the young man charged — by his supervisor — with the theft of construction materials.) Upon his release, pending the judge’s decision, he called to thank me. (Before I left our jail cell, I had given them my phone number.)

I told him that he wasn’t in the clear, that there was some work to be done before he was completely free. But, unfortunately, we lost touch with him and we have no idea what happened to him.

By the end of June, Bishwas was our only “success.”

In spite of all that, I decided no one in Nepal would be privy to my tears.

Within the first week of being back, I shared my stories with local journalists. Over the course of the several weeks that followed, I had more interviews, I met friends, acquaintances, relatives and cousins etc., individually as well as at a number of gatherings and social events. In most conversations I had with those who actually expressed an interest in my ordeal, we went over the facts. No one in Nepal hardly expressed an interest in — nor a curiosity for — my personal experiences. And so factual details was all I shared.

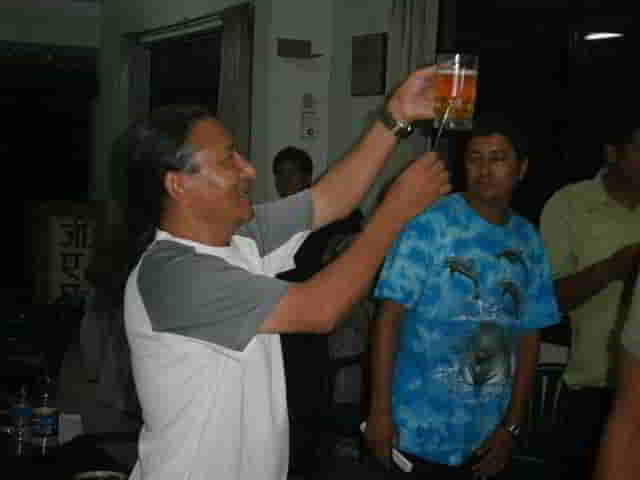

To give you an example, at an early July gathering of 23 Xaverian classmates — of all men and the biggest of our gatherings since my return — I got everyone’s attention by clanging a spoon to my beer glass (see image below) to share a few words of gratitude and a thing or two about the experience etc.

All I managed was just a few words, literally. My mates shouted me down, not rudely, but flippantly just as we have a tendency to do and have always done, pretty much all our lives at such gatherings, whenever someone has tried to be a little serious…too serious.

I don’t know what they thought I would say but clearly either they were not interested in it or they couldn’t feign interest. Or, it had something to do with Nepalese culture or Nepalese male machismo or something I haven’t considered here. (That would be the first and the last time I would try to talk to them, in person, seriously, about some aspect of the ordeal.)

And so it was with my tears and me in Nepal: no one would ask about the deeply — emotionally and psychologically — troubling and traumatic aspects of my experience (such as that which made me tear up regularly), and I would tell no one!

I did, however, tell my international friends.

The afternoon of May 12 when Chotu’s memory had made me sob uncontrollably, saying, “There is a little kid, maybe 19, in there and he has no clue why,” one of those international friends had given me a shoulder to cry on.

Not long after my return to Kathmandu, I started a fundraising drive: Education is Freedom. On June 25, five days before the end of the drive I published a blog post as a final plea and a challenge in which — surprise, surprise! — I shared Chotu’s story, but nothing about the tears.

Five days later, I shared — in a PM to that friend — a link to that blog post and some details of my struggles.

What do you think?

thank you Dorje for your beautiful writing and heart felt compassion for this young man and all whom you meet.

Dear Frances,

You are welcome!