This is the third and final installment in the three-part, blog-post reproduction of the presentation I gave at the Red Cross Nordic United World College, some time in the academic year 1996-97, about tourism and development aid in Mustang.

The introduction — with a bit of the recent history of the region and the circumstances under which Upper Mustang was opened up for tourism — was reproduced in the blog post “The local people should improve the quality of their lives.” […] “But let them not wear ties.”

The second part about tourism — relatively new in the region at the time — and its negative impact on the people of the region was reproduced in The Ugly Face of Tourism in Mustang in The Nineties.

In the introduction, I had mentioned how, after being closed off to the outside world, the government of Nepal had moved into Mustang in the mid-seventies to “develop” the region. But little worthy of note was done.

After the opening of the region to tourism, however, came a new wave of “development” agents. In this part of the presentation, I touched on what they did and didn’t do, and what we, as people, in general, need to do to make social and economic progress and to be able to live together harmoniously.

* * * * * * * *

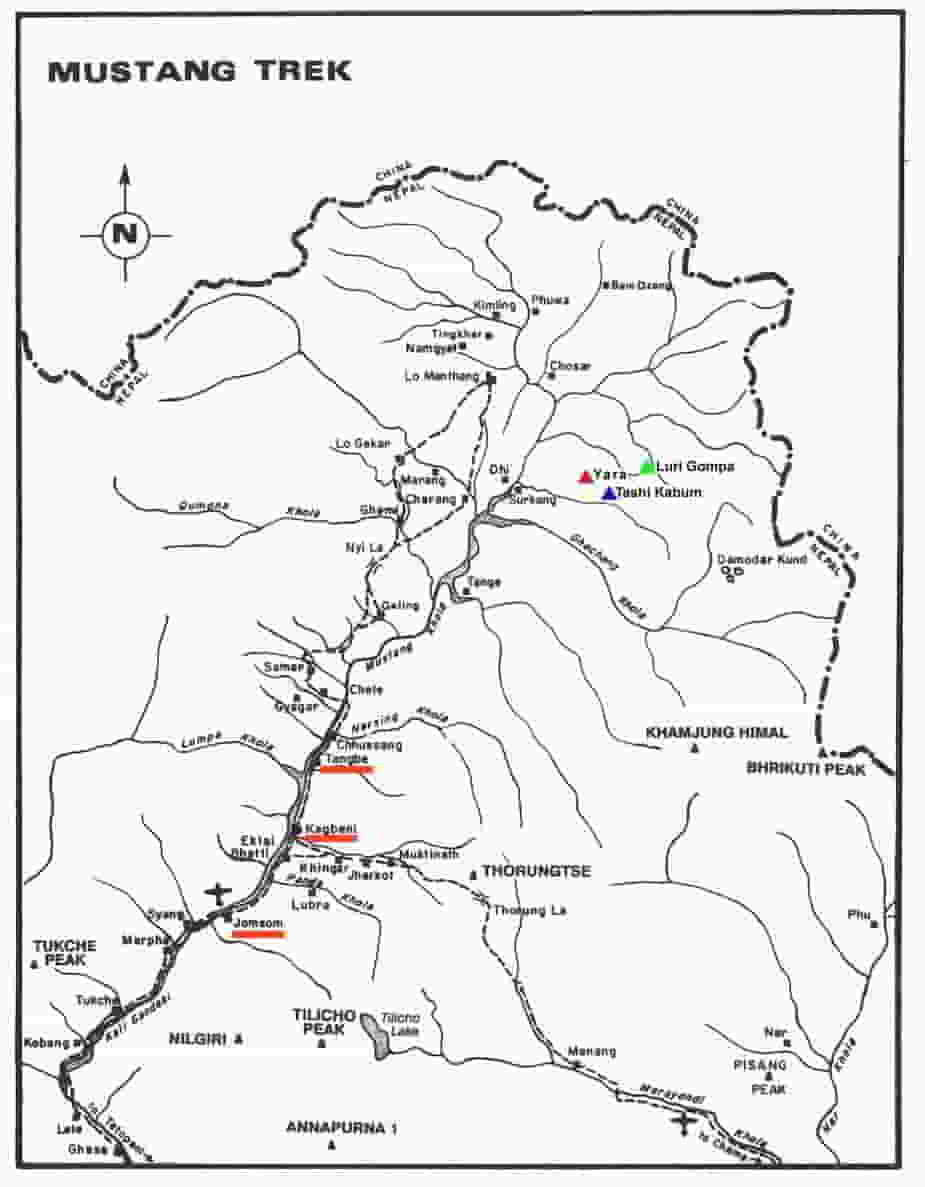

First Tangbe. My village saw the beginnings of its first development aid program financed by foreign donation in the fall of 1994.

The irrigation canal needed renovation at the source. A prominent member of the community, my [maternal] uncle had managed to secure the support of CARE Nepal.

They would provide the materials, technical support and arrange for their transportation to Jomsom upon receiving contributions from the village for it. The village was to arrange and pay for the transportation from Jomsom to the village and provide labor.

The aid agency, financed by Western and Northwestern European donor-countries such as Denmark and Netherlands, after surveys and assessment of the needs by their overseers and engineers, had approved plans to use polyethene pipes.

Each house had paid approximately 6 dollars to cover transportation costs which, incidentally, had been paid to CARE Nepal. The pipes and cements had been brought. But for some strange reasons unknown, CARE Nepal had taken upon themselves to transport everything all the way to Tangbe!

All of this had been taken care of in the fall of 1994. When I arrived in the village, the summer of 1995, the 60 polyethene pipe, each about 6-7 feet long, and the dozen or so sacks of cement hadn’t budged an inch — they were neatly stacked away under the chorten [stupa] at the entrance to the village.

To make a long story short, new engineers and overseers had come on the scene a few months earlier, carried out another study, and decided that iron ducts should be used.

The iron aqueducts would be donated free of cost, they had said. The village would have to bear the transportation costs, as with the polythene pipes, and each house would have to transport about 350 kg [770 lb] of sand from the river bed to the site of renovation. [Most of the 100 inhabitants, incidentally, are elderly.] The cost of transportation this time was calculated at 8 dollars per house!

I found most of this out the evening before I left the village. On my way down South, I came across the people carrying the aqueducts. They were about 10 feet long, weighing at, I was told, 79.5 kg [175 lb].

But here’s the mind boggling thing. My uncle had all along known how to renovate the source — he was the handyman of the village, one of the most resourceful and skilled villager. But as the village lacked the materials and man power, he conceded, they had been forced to rely on donated material and outside expertise. And this time around, some internal politics had also divided the village (of a hundred) into two camps preventing him from taking the reconstruction into his own hands.

One of the questions that some of my relatives kept asking me when we were discussing this that evening was: “Why would they make us do this?! Why are they putting us through something like this?!”

My answer was: “They must have made a lot of money, in pay-backs and commission, from the new contract they secured with the factory making the iron aqueducts, for instance.”

A visit to the CARE Nepal office once I was in Jomsom produced no straight answers.

And that was the first development project of its kind; one financed by some foreign governments and channeled through Kathmandu…. And there were rumors of a solar powered generator in the village!

A major development project in other parts of Mustang has been that of electrification.

The belief being that electricity reduces the consumption of wood and helps in the preservation of what little patches of forests remain. Small scale, locally initiated and managed projects such as those in Purang, Jharkot, Charang, and Marang have been successful — in providing some electricity.

This is the village of Jharkot, and last summer I found not only light bulbs and running water in various corners of the village, but also CNN, BBC, MTV, and numerous other Indian, Hong Kong, and South East Asian satellite channels on TV. All a result of the single-handed effort of Bikas Pandey, a US-educated Nepali I happen to know indirectly. [He is a fellow Xaverian.]

The first of those electrification projects Bikas was involved in while the others appear to have been the brainchild of some European donors. However, projects that involved foreign donors appeared to have been a complete fiasco.

Bikas had secured — from an American organization — promises of finance for a small scale hydroelectric plant [micro-hydroelectric plant] in Lo Manthang [Mustang in Nepali and English], the capital of the old Kingdom. He had traveled all the way up to Lo Manthang, convinced the locals — which in itself had been no easy task — that electricity would be a boon to the village and had given the go-ahead.

It was not until after six months since his return to Kathmandu and filing a report with the American Organization, that he finally heard from them.

Their answer? They did not have any funds available for the scheme anymore.

Another European aid in the region involved a wind-powered electricity in Kagbeni [image below].

Anyone with any knowledge of Mustang would have realized the incongruity of such a scheme — Mustang is notorious for its howling winds which at times reaches, I am told, speeds of up to 100 miles an hour.

Within three months, the blades of the wind-turbine had shattered. What remain are the turbins, the wiring in the houses, and the Dutch-made (!) steel poles in the alleys of Kagbeni. Another telling vestige of the project — the project office — lies abandoned and unused inside a compound with locked gates.

Such symbols of disaster lie all along the Kali Ghandaki river, and, I have read, also the Khumbu area.

What I have recounted and enumerated are only a few problems involving tourists and development aid in Mustang. However, as some of the very first effects and influences of tourism, and the very first results of development projects, if these are any indication of the future to come, then, tourism and development aid for the people of Mustang means, among other things, compromising self-determination, loss of dignity, insult to their intelligence, and in some cases an insult to their very own human being.

But, as a country, Nepal will not be able to do without tourism. It brings in significant amount of foreign exchange and is vital to the economy. And development aid, started half a century ago, has planted itself so firmly in so many areas that its discontinuation would simply be impossible. I don’t know if there is an easy solution to this.

What I do know however is that individuals must work from their heart if they are to make a significant and positive contribution to the lives of another people.

First has to come the relationship, then understanding and respect, and then mutual cooperation. I am going to let Robert Persig say the rest.

“I think if we are going to reform the world and make it a better place to live in, the way to do it is not with talk about relationship of a political nature . . . or programs full of things for other people to do. I think that kind of approach starts it at the end and presumes the end is the beginning. Programs of a political nature are important end products of social quality that can be effective only if the underlying structure of social values is right. The social values are right only if the individual values are right. The place to improve the world is first in one’s own heart and head and hands, and then work outward from there.”

– Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

* * * * * * * *

Here’s an update on the Kagbeni wind-turbine project. According to this My Republica article written by Hari Krishna Gautam and published on Dec. 18, 2015, a Danish organization started it in 1989. At a price tag of apparently Rs. 10 million (which at the exchange rate then would have amounted to more than US$250K), the turbine was in operation for “just two months.”

It goes on to say, “The windmill failed to uphold strong winds coming from northern direction and broke its two wings.”

(I used to have photos/slides of the derelict windmill with broken blades etc., photos I took myself, but I can’t find them!)

References

Thapa, Manjushree. Mustang Bhot in Fragments. Provides details of many of Bikas Pandey’s electrification work.

Pye-Smith, Charlie Pye-Smith. Travels in Nepal – the Sequestered Kingdom. Provides an excellent account of the development aid industry in the country.

Hancok, Graham. Lords of Poverty (1989). Provides an excellent account of the development aid industry in general.