Yesterday afternoon I presented — to Teach For Nepal (TFN) Science Fellows — a talk about teaching higher level thinking skills in Science lessons.

TFN places volunteer teachers in rural schools for two years. As part of my efforts to improve science teaching in Nepal, I volunteered to talk to them.

Normally, I record my presentations and combine the audio with the visuals to create a video and post them on my YouTube channel and blog. When during this presentation, I noticed some of the Fellows taking notes, I told them about that. Except at the end of the presentation, I discovered my iPhone had recorded only 25 seconds of the presentation! I don’t know what happened. 🙁

So, what I am reproducing below are the important bits using my memory, notes and images from the PowerPoint slides.

* * * * * * * *

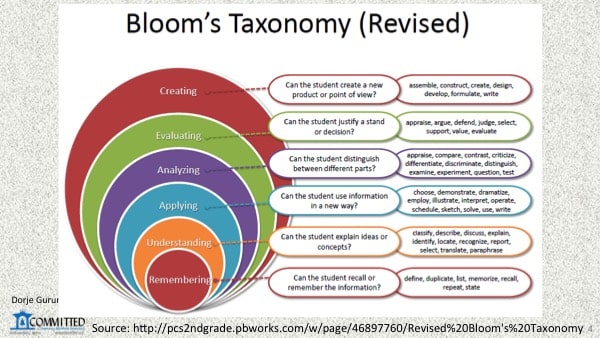

The following image shows cognitive processes according to Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Going from Remembering at the bottom to Creating at the top, the skills get more complex.

The higher level skills start with Analyzing and end with Creating. You can see what those skills entail/involve.

I am sure you’ll agree with me when I say that in Nepal, schools generally impart mostly the most basic of the skills: remembering! There is some understanding being imparted and some application but very limited.

The higher level skills are pretty much completely and totally ignored, especially in government schools.

If we are to improve the quality of education in Nepal, we have to teach our children to think. In other words, we must impart higher level thinking skills.

[bctt tweet=”To improve the #QualityOfEducation in #Nepal, we have to teach children to #think.” username=”Dorje_sDooing”]

What kinds of activities best promote and impart higher level thinking skills?

Higher level thinking skills are processes. And so, the best way to learn/teach those skills is by engaging in processes. The process of finding an answer, or solution, to open-ended problems is one of the best!

Open-ended problems create environments that encourage and foster analysis of information and data, drawing conclusions from them, then evaluating those conclusions and synthesizing those conclusions and observations to generate new insights and possibly to create new processes!

[bctt tweet=”Open-ended problems encourage #HigherLevelThinking and foster #HigherLevelThinkingSkills.” username=”Dorje_sDooing”]

What I am going to do for the rest of the presentation is to actually run a science lesson with you, to show you an example of that. So from now on, you will pretend to be my student!

[Next I had the Fellows split into groups and pick up a candle each of three different thickness, a glass, a bowl and a box of matches that I had had TFN personnel prepare for me.]

Remembering that you are all science students, studying the science of a burning candle, share what you see, hear or smell with other members of the group.

And after you have had a chance to do that, I’ll ask you to share your group’s observations with the rest of the class.

[I gave them some time for that. After that I had a speaker from one group share their observations. Following that, I asked the speakers from the rest of the groups to add to that if they had anything different.

We had a number of discussions but discussing some of the observations, I drew their attention to the difference between an observation and conclusion when at least two speakers mentioned oxygen and carbon dioxide in their observations.

They wouldn’t have “observed” either of the two gases because they are both colorless and odorless!]

Being students of mine, being science/chemistry students of mine, you should know the chemical process taking place when a candle burns.

What happens, chemically, when something like a candle burns?

[They were able to give me the equation for the chemical reaction which I put up on the white board. Next I told them they were going to conduct an experiment.]

Your prediction must also be accompanied by an explanation.

[I gave them time for the experiment. I talked to different groups about what they were discovering etc. At different times, I stopped them and discussed how what they are doing is simple analysis of their observations and drawing conclusions etc.

But the important thing I shared with them then was the fact that I did not know the answer, implying, of course, that the problem was an open-ended one!

Someone came around to take photos of the “lesson” copies of which I have been promised. When I get them, I’ll be sure to update this post with them.

I also had them investigate an extension to the experiment. They tested the time for which different lengths of candle of the same thickness burn.

The last activity was inverting the glass over a burning candle inside the bowl with some water in it.]

[At the end, I had them share their discoveries and answer the questions I posed in the above slide.]

To conclude, open-ended problems such as these allow teachers to impart higher level thinking skills.

When students conduct these experiments and also expand on the scope of the investigation when, for whatever reason, the experiment has to be modified or changed, the student invariably goes through the processes of applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Plus, writing a report about the investigation also provides opportunities for the same.

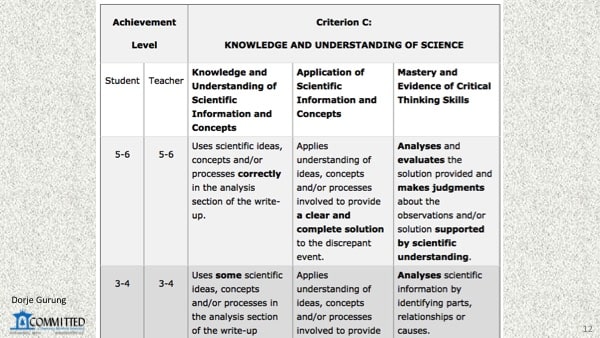

When I used to have students of mine conduct these kinds of investigations, I had them write-up reports which were assessed on the following criteria among others.

Notice how Analysis and evaluation are part of the grading criteria.

[Then I rounded off the presentation by sharing some of what I have discovered about being a teacher. I have made a number of discoveries, but what I shared, as you can see below, is relevant specifically to teachers in Nepal, because of both the culture of the country in general and the school culture in the country specifically.]

What I have put up there is very much in contradiction to expectations in Nepal. It’s a given that you don’t know everything, and that should not really be a problem.

And even that you might not know all the science you are expected to teach is really all right.

And finally, it’s ok when you don’t have the answer to every question posed by students, and to even tell them that you don’t know the answer. I know, in Nepal, you are NOT supposed to do that. But ask the student to find the answer for the next lesson to share with the class. For some students, that can be the most empowering and encouraging experience.

The most important thing to remember is that you are a guide! That you are there to point them in the right direction.

As such, you must be willing to learn and, as a matter of fact, must be constantly learning to improve your teaching and the learning outcomes of your students.

Being a guide, who doesn’t have all the answers, means that at times you’ll explore and discover answers to questions together, with your students, as you engage in activities alongside them.

Along those same lines then, here is some advice:

You don’t have to put on a facade as is expected of you in our country by the culture, by the parents, by the students etc.

Just be yourself and be true to yourself and enjoy teaching.

That’s pretty much it of the presentation, thank you and good luck!

[During the Q&A session, I did concede that our school and education culture, and education system — requiring the preparation students to regurgitate answers to questions in examinations — makes it difficult for teachers to plan these kinds of lessons and activities.]

Aug. 25 Update

I recently received the photos. Here they are. Click on one to browse through them.

References:

The Examined life. About what is wrong with our education system around the world. Teaching students to “think for themselves” will make them, it argues, “more adept at interpreting questions and making the important transition from descriptive to argumentative and evaluative responses. In short, if students have learned to think better, they will be able to think better about what to do when the exams come around.

“Yet, despite the evident advantages of teaching students to think philosophically, the dominant mode of education remains staunchly traditional and of a particularly stultifying character.” (Emphasis is mine.)

Updated on October 17, 2016 with the References section.