An op-ed I read several days ago about Tamangs and shared on Facebook with a commentary of my own, prompted me to revisit the highly stratified and hierarchical Nepalese social structure which is at the detriment of a vast majority of the population, and therefore the country itself.

The stratification and hierarchy was created, maintained and perpetuated by the hill so-called high caste Hindus — Brahmins, the priestly caste, and Chhetris, the warrior caste — for obvious reasons: firstly, to exert social, political and economic control over the rest of the population of the country, and secondly, to legitimise their higher status.

They went as far as to codify the caste system in Muluki Ain (“Law of the Land”) in 1854. The highly discriminatory system was the law until 1963 when it was changed but has never really been enforced, not even today.

Social protocols, interactions and dynamics, and professions people can engage in — especially the lowest caste — all reinforce the hierarchy, the high castes enjoying many hidden structural privileges that most probably neither pause to think about nor are even aware of.

Nepali, the mother tongue of Brahmins and Chhetris and the national language of the country, naturally, also reflects the social structure and reinforces the hierarchy. For instance, it has four different forms of the pronoun ‘you’: the first form tã — depending on who you are addressing — is either just very informal, and so denotes closeness, or demeaning; timi, the second form, is somewhat formal; tapai is formal and respectful; and hajur is very formal and very respectful.

It is not unusual for high castes of any age to use the least formal form of you (tã) when addressing lower castes, for instance, especially the lowest caste — Dalits — regardless of their age.

At the same time, some high castes use an even more formal language when addressing one another with verb conjugations the rest of the Nepalese reserve for the royalties. One of the reasons for that may have more to do with their own perception of themselves than anything else!

In Nepali, there are also the concepts of “ones place” and of “knowing ones place,” which, among other things, is “ones place” in the caste-based social ladder.

What’s more, when someone is perceived to be demonstrating a lack of knowledge about, or appears to have forgotten, his/her “place,” like by someone from a lower caste, there exists the idea of “putting the individual in his/her place.” This may happen when someone of high status perceives another individual of lower status to have displayed behavior unbecoming of their lower position and thereby offending the former!

The offended party, under these circumstances, may choose to “put the offender in his/her place” by addressing them using terms and/or labels reserved just for them designed to humiliate and/or intimidate.

A term such as Bhote (or Bhotiya) when it comes to ethnic Tibetans — like myself — from along the northern borders of the country, for instance. This happened very publicly on Facebook a few months ago.

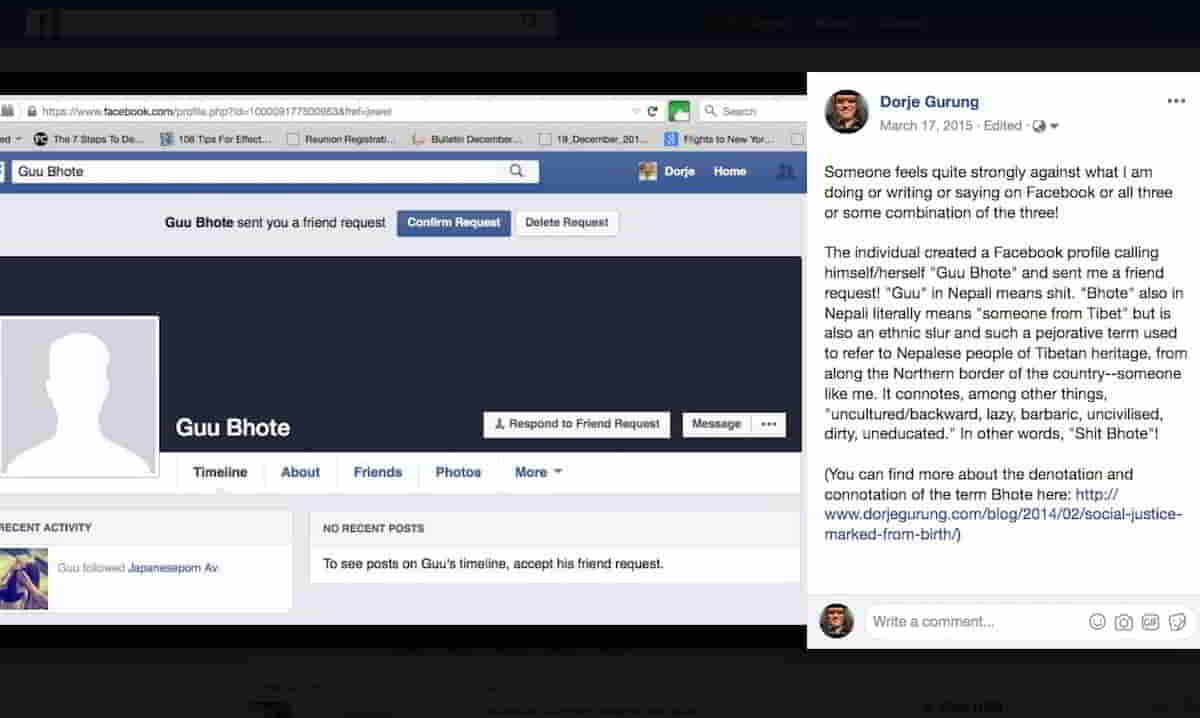

Someone clearly angered or offended enough by something I must have said or done on the said social media, or elsewhere, created a Facebook profile calling (most likely) himself, Ghu Bhote and sent me a friend request! (Realizing that this was clearly the work of a coward, I posted the details of the request on Facebook. See image at the top.)

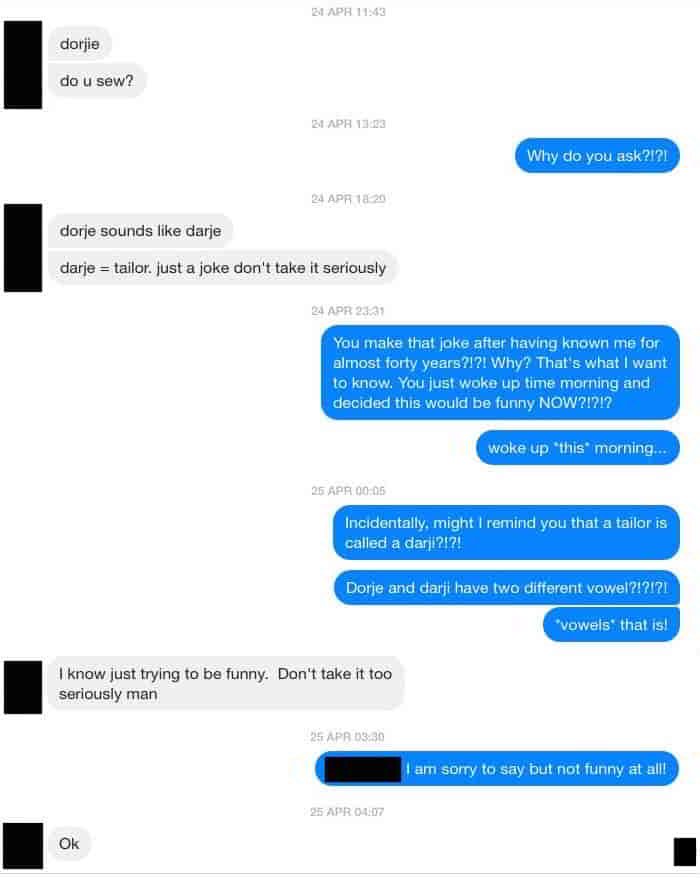

Or a term such as the one a friend used in a PM exchange I had in April, a little over a month later. (I have redacted everything that might identify him since the reason for sharing this is NOT to publicly embarrass or humiliate him.)

To point out only three of the things that stand out.

Firstly he changed my name to Darjie to make it sound more like Darji or Darjee, Nepali for “tailor.” (Tailors, incidentally, if you haven’t already figured out, belong to the untouchable caste.) Secondly, he twisted the spelling of Darji to Darje to make it sound more like my own name! And thirdly, he felt compelled to share this joke after over six hours of initiating the chat!

(Had he been aware of any of that? Or had they all been deliberate?)

Be that as they may, there is a side story to the two incidents which may appear — to some — to be interesting…or not.

The first incident — the Facebook friend request from Guu Bhote — followed in the heels of an extensive Facebook exchange with Nepalese friends between March 8 and 16, in which a number of interesting revelations were made. The friend request from Guu Bhote came the following day — on March 17 — after the last comment was made in that exchange! Without any additional information, it’s hard to say whether the timing was just a coincidence or related.

But the individual responsible for this was either stupid enough to give away the fact that he was in Thailand at the time and/or also speaks Thai, or smart enough to give those impressions to mislead everyone.

What there is no doubt about however is that it was clearly designed to “put me in my place.”

As for the darji exchange, it took place between April 24 and 26, more than a month after the March Facebook exchanges. That this may have something to do with those exchanges I cannot tell, though, this particular friend also contributed.

* * * * * * * *

I am no stranger to being labeled — both in Nepal and abroad. But not all the names and labels have been demeaning and/or designed to humiliate and/or intimidate, of course!

The earliest one is of someone calling me “Dirty Bhote.” To that now I can add “Guu Bhote” and “Darji.” Outside the country, I have been called everything from “Paki,” to “Mexican,” to “Red Indian” to “Eskimo” (“One who lives in an Igloo”) to “Ching Chang Chu,” to “Jackie Chan” to “Mzungu” to “American” etc.

Similarly, while in Qatar I might have been treated like I was at the bottom of the heap, in Malawi, it was the opposite: I was treated like I was near the top of the pecking order!

However, I place very little value in names and labels and, by extension, social status.

What I told, a while ago, another classmate when, towards the end of another similar private exchange, he tried to shut me down by calling me an “idiot” comes to mind: “If only your calling me an idiot made me an idiot.”

If only a human being were reducible to a stereotype…if only a human being could be completely defined by the mere social construct of social status…if only I could be intimidated and silenced by cowardly tactics…if only!

Sadly, however, demeaning, humiliating and intimidating others through language and words is one of the weapons of choice of those who feel they are somehow superior and feel the need to demonstrate that, whatever the reason for their sense of superiority is — caste, gender, class, skin color, nationality or the size of their wallet, you name it.

[bctt tweet=”If only a human being were reducible to a stereotype…” username=”Dorje_sDooing”]

The high castes and other Nepalese who look down on the marginalized and the disenfranchised fellow Nepalese as inferior and less deserving of the resources of the country, wield this weapon to “put them in their place” often.

Tamangs and Dalits are just two of the many marginalized and disenfranchised Nepalese.

Tamangs, who — according to this article — suffered the most casualties in the last two earthquakes partly because of a long history of discrimination, abuse and being “put down” in their place.

Dalits, such as Pandav Mallik, who are “put down” all their lives, ALL THEIR LIVES! If you think I am exaggerating, follow the link and read his long and harrowing life story!

All that naturally brings me to the question, “What are you doing about it?”

One of the number of things I am doing is writing about it — and thereby raising my voice against and awareness about it. If people like myself don’t, the next generation of Nepalese — including people like my little nephew and other children like him from my community — will for sure be discriminated, mistreated and humiliated. (I devote a whole series to Social Justice.)

I also give talks and presentations at different venues, notably educational institutions both in Nepal and abroad about the caste system, compassion, (international) understanding and (world) peace. Of late, I have spoken at a number of institutions in Nepal, in Hong Kong and schools and tertiary educational institutions in the United States of America.

COMMITTED’s project site Thangpalkot is in Sindhupalchok, most likely the district with the highest concentration of Tamangs. Apart from working in the area to improve the quality of children’s education, until the earthquake of April 25, we had also been helping the schools and locals set up fisheries to help the school become self-sustainable and to make the locals self-reliant. We had also been providing scholarships to both Tamang and dalit children, to encourage and motivate them to stay in school.

We have also been supporting other marginalized groups of Nepalese, such as the children of migrant laborers who have died abroad, children of poor families.

In doing what I can for the education and empowerment of marginalized and disenfranchised children, whether at COMMITTED’s project sites or elsewhere — such as when I volunteer with the UWC National Committee and raise funds to send children from low socioeconomic backgrounds to UWCs — I am endeavoring to create roles models who, I am hoping, will make a positive impact in their own communities by becoming agents of change themselves long after I am gone.

Since the earthquake, following the destruction of most schools and houses in Thangpalkot and its neighbors, COMMITTED decided to take a few steps back and to be involved in emergency relief and rebuilding of schools. The way Jayjeev and I work, we should be able to help and encourage the transformation of that all-influential other structure which the earthquake does not seem to have leveled: our caste-based social structure!

In the post The Good The Bad and The Untouchables, I described how we have two groups of untouchables in the country: one group no one wants to touch and the other no one can touch. In all COMMITED and I do, we hope to bridge the huge gulf between the two, through education, to create a more just, harmonious and progressive society for the benefit of EVERYONE, and thereby contribute to the social progress and development of the country as a whole!

* * * * * * * *

References:

The country is yours. The Op-ed by Deepak Thapa about the plight of Tamangs and the arrogance and bigotry of even current high-caste government officials.

The Invisible Doko. The hidden privileges of being born a high-caste Hindu in Nepal most of whom probably hardly ever think about.

The Tamang Epicentre. Details of the different reasons Tamangs disproportionately suffered from the earthquake, one of which is the historical neglect of the people by Kathmandu and its elite.