There is no shame in birth as a low-caste (or as anything that signifies low status in a society for that matter). The shame to me, really, is in the way others mistreat and put obstacles in the paths of those that they view an less worthy and prevent them from realising their full potential.

Late afternoon of December 8, after an uncharacteristically luxurious journey to Thangpalkot–a rental Landcruiser taking us from COMMITTED office all the way to the school–we had arrived at the village in about 6 hours on the 80 km bumpy and potholed road. One of my goals during that visit had been to learn about the situation of Dalits in the VDC.

While the team was inspecting the newly built bamboo shed next to the pond, I was busy taking photos of the children who had gathered around us and were being just children! They were playful, making faces when I would take their pictures. They would cajole us into letting them go for a boat ride on the pond etc. just like any bunch of children. Except they weren’t just any bunch!

Photo shoot over, as I didn’t recognize any of them except for Samir, I asked for their introductions, about who they were and about their schools just as I always do with children I meet. One by one they gave me their names. Most of them turned out to be Dalits, either a damai (tailor) or a kami (blacksmith). (These incidentally were the children I referred to in another post also about the December trip.)

When it came to talking about school, a number of them recounted how they are looked down upon, how they are ridiculed or mocked or poked fun at by other children for being Dalits.

“When I was carrying some food to the school once, other students poked fun at me saying that I was shaking and trembling.”

“Other students won’t let us play with them.”

That explained why they were hanging out together that late afternoon.

And to, “Where do you all live?”

“We live in Damai Tole [(Tailor Street)].”

“The Kami’s all live on Kami Tole [(Blacksmith Street)].”

The night of December 9, tucked under two layers of warm blanket following a sumptuous dinner of fish and all, Jayjeev and I had another one of our typical nights in Thangpalkot: we talked and talked about pretty much everything. Apart from reminiscing about our childhood and my own ostracism in 4th grade, we talked about the Nepalese Caste System which is responsible for the plight of Dalit children we had met the afternoon of December 8.

If I suffered from discrimination as a child, how much more must Dalit children suffer? How much more easily must Nepalese society condemn a Dalit child? Very easily it seems. Very very easily. Their homes being segregated from the rest of the village is but only one of many ways they suffer.

The following afternoon I went on a tour of Damai Tole and Kami Tole. Just the village of Thangpalkot has about 30 Dalit households. I am told, in the areas of Thangpalkot and neighboring Gunsa, there are about 45 Dalit households in total, all segregated. This, I understand, is the arrangement in most other villages in the country as well.

They are segregated because high caste members consider them to be untouchables–“polluted” or “polluting.” Physical segregation of their houses is but only one of the measures the high castes take to make sure that the Dalits don’t come in contact with them and thus don’t pollute them or their belongings.

They are segregated at social gatherings and functions as well. Boys like Samir or Sagar may have roles, such as playing a small drum at a wedding procession. But at the end of the procession, the boys would be made to sit separately from the rest of the participants, at the very back for instance, if included at all.

When visiting another villager’s home or a tea house or restaurant etc. Dalits, like Kabita would not be allowed to enter the home or establishment or sit where the rest do. If fed, she would get the food on plates etc. left outside the house. At the end of the meal, she would have to wash and return them to their place. No one else, no one in the house or any other higher caste visitor to the house, would ever handle the utensils, because they would be considered polluted, unclean.

In some places, little girls like Sanju with household chores such as fetching water, might not be allowed to fetch it from the community tap. She may be required to get it from some other tap reserved just for them, which may be farther away and/or of a poorer quality. Or if she had the option of using the community tap, she may be required to defer to higher castes as and when they arrive on the scene. All again because she is considered “polluted” or “polluting.” There are a number of other ways our society mistreats Dalits.

Young Dalits are thus made to live virtually outside the society, in a world of their own, isolated and ostracized with severely limited opportunities, for no fault of their own.

Having suffered from discrimination myself both as a child in Nepal and as an adult abroad, I am fully aware of what it does and can do to a person. Being mistreated thus, Dalit children, for example, are forced to learn something deplorable about themselves.

They grow up learning that they are worth less than their non-dalit counterparts. By the time they reach their teens, most of those little boys and girls we met will come to believe and accept that they are beneath the high castes and everyone else, that they are indeed worth very very little or even worthless, having been treated as such for years!

By the time they are in their late teens, they will have learned, through reinforcement by the rest of the members of the society, behaviors befitting them–such as not talking back at high castes, being subservient, obsequious etc. They are thus pressured to–and many do–accept their fate and go through life with their heads held low, literally and figuratively, in shame. The ones that are made to carry such shame the most are young Dalit girls and their mothers.

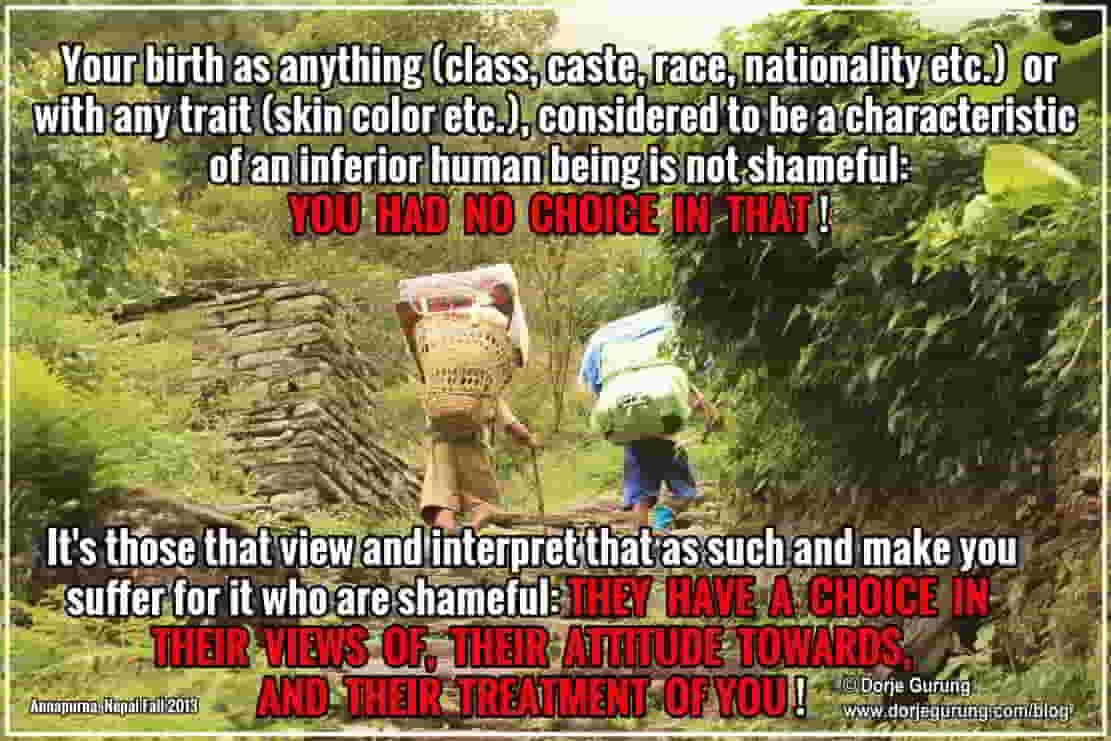

BUT that shame is NOT theirs to carry. It’s for others that cannot see and accept context and circumstance of birth as random as the number that comes up when you roll a dice to carry that shame.

It’s for others that mistreat Dalits (and those they consider inferior) just so that they can feel superior for no logically valid reason to carry that shame.

It’s for others that cannot see the humanity in another human being, for others that cannot empathise with fellow human beings, but instead sustain and perpetuate this social ill to carry that shame.

Laws exist that make discrimination based on caste a crime. But in a country where all that the leaders, politicians and bureaucrats are interested in are money and power, who cares if such laws are broken?!

In the mean time, behaviors of both the Dalits and non-dalits MUST change. As a country, the human cost of the ostracism and mistreatment of a people that makes up, according to official statistics, 15% of the population cannot be ignored. (I have read a number of literatures in which they say the estimate is closer to 25% in reality.)

And all I know is that education will help.

Education of firstly the Dalits. To that end, COMMITTED and I have already begun sponsoring the education of a number of Dalit children in Thangpalkot: Sagar and Samir, Samir Pariyar, Sanju Pariyarand Kabita Biswokarma.

Secondly, education of the rest of the population — a population that perpetuates this deplorable system whether intentionally or unconsciously. They must be educated to accept that their way of thinking about and classifying people based on the Caste System and mistreating them accordingly is outmoded and outdated. These same people, who, if told to look themselves in the mirror and ask themselves if they would accept the same level and kind of mistreatment of their own children by others based on some such spurious logic, would say no, must be educated.

Apart from providing educational opportunities to Dalit children, my hope is that my writing about it will also create some awareness and, thereby, contribute to change and transformation of our societies, however little and slow it may be.

Great read.. Thank you for writing this.

Bhim, you are welcome!