In a number of other posts, I hinted at the discrimination I have faced in Nepal. The first time I made brief mentioned of it was in Qatar…From Afar: Irony of Ironies. In My Potholed Road to UWC, I described briefly what Bhote both denotes and connotes in Nepalese. Additionally, Casualty of Qatar: Shattered Dream? I stated how my struggles resulting from the circumstances of my birth — in a low socioeconomic background — almost meant the death of my childhood dreams. And finally in a recent post — Social Justice: Social (Media) Status Upgrades — I mentioned how the details of my own struggles would have to remain a subject of another post.

This is that post.

* * * * * * * *

When visiting Thangpalkot, I look forward to the long evening chats I have with Jayjeev. They often run well into the night, even after the lights are off. Work, family, our hopes and dreams for the communities we serve, our hopes and dreams for the children of the village and the country figure into our conversation, topics I rarely — if ever — discuss with most other friends in Nepal. Memories of our school days are also part of our conversation.

The night of December 9, the second night of our December visit to Thangpalkot, tucked under our respective blankets, we were having another one of those conversations. It started with us talking about the Dalit children we had met the previous afternoon (about whom I’ll have more to say in another post), which led to us reminiscing about our own childhood at St. Xavier’s Godavari school, the Jesuit boarding school, and specifically about a particular incident in 4th grade when I was ostracized by my classmates, just as those Dalit children appeared to be.

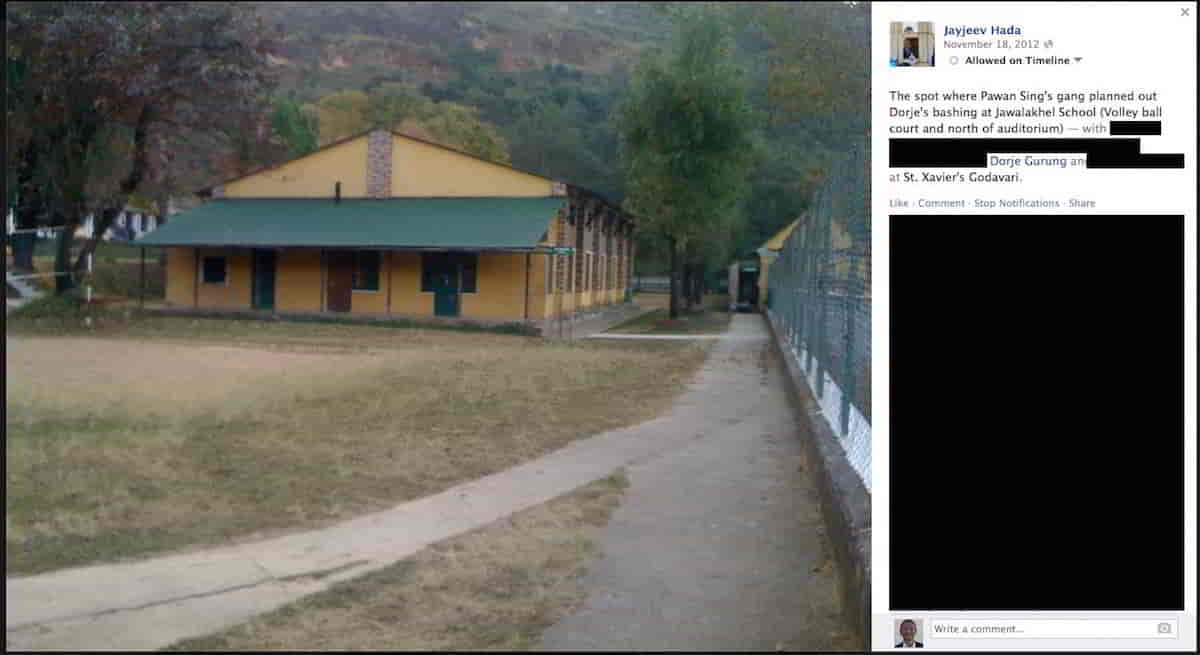

A small argument between two classmates in a playground next to the school hall (see image at the top) split the class into two groups. Following the argument, the two decided that they would not be talking to each other any longer. Over time, one by one, other classmates either sided with one or the other friend. When friends asked me who I was siding with, I told them neither because both were friends of mine.

But, over time, pretty much every classmate joined either one camp or the other, except me. So, for some time, the class consisted of three groups — the other two groups and me! Things took a turn for the worse for me when the two “enemy” friends made up and all of them became one big happy group leaving me all alone. Somehow, they decided they would gang up against me and ostracise me. Somehow, I ended up being the target of the ire of the rest of my classmates!

They would have meetings to discuss their plans to beat me up when we moved to St. Xavier’s Jawalakhel, the secondary school in Kathmandu city. At one such meeting, a classmate supposedly laid out a detailed plan for how he would have me run over by his big car! (See image above.)

I learned about these meetings and their plans from two classmates. I never knew whether those two reported everything to me because they wanted to scare me or because they felt sorry for me and wanted to keep me informed or just because.

Ostracized thus, I had no classmate or adult who I could ask for a reason or explanation for why. I didn’t understand how an argument between two other classmates ended up with me being ostracized by all of them. I realised I had to find an explanation by myself, for myself. The explanation I came up with — rightly or wrongly — was because I was a Bhote.

Even though I was just a young child of about ten, I had already experienced and learned enough about what being a Bhote — a low caste — and, in general, what being from a low socioeconomic background meant and how others saw and viewed me.

A flat and round face, and small eyes, features that came with my birth as an ethnic Tibetan-buddhist, i.e. a Bhote, meant a relegation to a low-caste within the Nepalese society. Birth into a family from the small village of Tangbe in Mustang district, meant a relegation to the rung just above the one occupied by the untouchables, the Dalits, in the social ladder within the Mustang-district community. I would discover pretty early on in my life the many implications of birth in a low social class in Nepal.

The first incident took place before I moved to Godavari School. A kid ended an argument I had with him by calling me “dirty Bhote.” I remember asking my mom later that day why it was that they characterised us as “dirty.”

I never forgot my mom’s response: “We are as dirty or as clean as they are; we shower as often as them.”

But that didn’t stop other Nepalese from viewing me the way they did and letting me know as well. Pretty soon I realised how others considered me less worthy, less able, dirty, uncivilised, etc. etc. solely based on the circumstances and context of my birth.

However, to hide our Tibetan heritage — and avoid being discriminated against — my father and his friends, the first generation of Tangbetanis to move to the cities, gave themselves and their children Nepalese (i.e. Hindu) names and surnames. Most adopted the Nepalese surname of “Gurung,” a hill tribe with physical features, culture and tradition similar to ours. That didn’t help much however.

When admitted to St. Xavier’s Godavari School, my dad dropped my nepalese name. He combined my first Tibetan name (Dorje) and the surname Gurung to come up with my new name, thinking that the Nepalese government, in the future, might enact policies to benefit those from remote parts of the country. Unfortunately, the person who filled out my bio-data — on my father’s behalf — transcribed my name as “Dhorcha,” which, sounding close to the Nepalese word “Dhocha” meaning “Tibetan shoes”, became yet another source of embarrassment for me. (All my official school records, certificates etc. until grade 5 has me down as Dhorcha Gurung.)

So, there I was at St. Xavier’s Godavari, a Bhote, a low caste, with a name that sounded like it meant “Tibetan shoes,” pretending to be a Gurung, a hill tribe from outside Pokhara, fully aware that my facial features gave away my ethnic identity, fully conscious of and uncomfortable with all that…and then the incident happens in 4th grade.

Most of my classmates probably don’t even remember it, or if they do, remember only bits and pieces. Jayjeev, for instance, didn’t remember neither that we had been in 4th grade at the time nor that it had all started with a minor argument between two classmates.

I doubt any of my classmates were, or are, aware of or thought about or understood the impact, on me, of their ostracism and of the stories they floated around about beating me up etc. Every single one of us, after all, was a child.

Apart from making me spend the rest of the year with older friends in 5th grade, the incident would go on to shape and inform my future relationships with my classmates throughout the rest of my academic career in Nepal. What’s more, it may have even unconsciously affected my relationships with my Godavari classmates in later years more than I had known. I say that because, that night, talking with Jayjeev, I made a discovery I had missed all these years.

Graduating from St. Xavier’s Godavari primary school, the whole class moved on to St. Xavier’s Jawalakhel secondary school in Kathmandu city, where we joined Jawalakhel’s group of graduates. Only one of my five “best” friends during my high school years at St. Xavier’s Jawalakhel, I realized that night, had also been a classmate from Godavari school! Even that single friend had joined us at Godavari only in grade 5, and so knew nothing about the incident.

The incident would also shape and inform my relationship with other Nepalese. I would become a “good boy” and avoid doing or saying anything that would reinforce the stereotype of a Bhote (uncultured, barbaric, uncivilised, dirty, uneducated etc.). I did everything I could to avoid being written off by others saying, “What can you expect from a Bhote, who doesn’t know his place?!”

Most importantly, the incident would also put me on a path to being and creating my own person, and to dreaming big in order to prove them wrong and to ultimately succeeding in my quest!

Today, partly due to these experiences and experiences abroad, I place very little value in social status — it means very little to me. While living and traveling abroad most of the last twenty-five years, my social status changed so frequently and so drastically from country to country that it has stopped meaning anything. In Malawi, for instance, I had a high social status because of the combination of the job I had, the salary I was making and my skin color. In Qatar however, I was at the bottom of the social structure simply because of my nationality.

However, in Nepal now, I also recognise that any respect I have is ONLY because of my education, and everything else that followed from it. In a country where “source and force” (wealth and connection) and/or family name and/or where you are from means pretty much everything, and can make or break your life, I have very little of any of that. Social mobility is non-existent in this country, BUT education makes a difference, especially to people not born into privilege.

In my own home, we have come full circle. This morning I took my little nephew to his first day of school. While all of his almost thirty-month life, and for us the rest of his life, he will be known as Tenzin (P.) — his Tibetan name — he has begun his schooling as Soman Gurung. The social world he is growing up in, unfortunately, as far as I can tell, is not significantly different from the one I grew up in, but…he has me.

Furthermore, the Dalit children of Thangpalkot that got Jayjeev and I talking about all of this in the first place that evening, has us two. Those children, innocent and full of potential — marked from birth as being untouchable and therefore less worthy — but undeserving of all the unfair characterisation and mistreatment, they suffer considerably more. Some of the most basic human rights they and their families should be enjoying are violated on a daily basis, the details of which will have to remain the subject of another post.

We have put in place a sponsorship program and have begun sponsoring a number of them already. Samir and Sagar, two little boys full of energy, are sponsored by a friend and former colleague of mine. Sanju and Samir, two other Dalit children, are sponsored through Nemira-COMMITTED partnership Sponsorship Program. There are considerably more Dalit children in Thangpalkot. The village has two whole streets, segregated from the rest of the village, where all of them live.

I shall personally be following the progress of these children to let them know that there is someone who knows and understands what they are going through. That there is someone who cares about them, cares about their education and their dreams, to do all he can to ensure that they may grow up educated and respected for who they are as individuals and who they have become, just as it has been for me, instead of being stigmatized for life and being made to suffer because of the circumstances and context of their birth.

What do you think?

Thanks for sharing the story Dorje!

Childhood bullying and traumatic experiences shape our personality for the rest of our life! I do have bitter experience of being ostracized by group of friends while I was 15-16. This traumatic event has shaped my personality! And even now after 25 years when I’m quite stressed, I see those who ostracized me in my dream! Whole reason of discrimation was I did a bit better academically than a particular group of people who had different ethnicity/caste of mine! And ppl of my caste had already rejected me as I didn’t care this caste thing at all and had befriended with kids of different castes as what I cared was learning & curiosity. In the end, when I did a bit better than them, they, too, ostracized me!

Looking bsck in my own life, I always feel how terrible it must be to those poor Dalit kids who (& the whole Dalit community) has been always ostracized by our society since many centuries! This inhumane suffering MUST end!

Thanks for sharing the story Dorje!

Childhood bullying and traumatic experiences shape our personality for the rest of our life! I do have bitter experience of being ostracized by group of friends while I was 15-16. This traumatic event has shaped my personality! And even now after 25 years when I’m quite stressed, I see those who ostracized me in my dream! Whole reason of discrimation was I did a bit better academically than a particular group of people who had different ethnicity/caste of mine! And ppl of my caste had already rejected me as I didn’t care this caste thing at all and had befriended with kids of different castes as what I cared was learning & curiosity. In the end, when I did a bit better than them, they, too, ostracized me!

Looking bsck in my own life, I always feel how terrible it must be to those poor Dalit kids who (& the whole Dalit community) has been always ostracized by our society since many centuries! This inhumane suffering MUST end!

Dorje, your ” friends” are the reasons who you are today more importantly your own life experiences and rediscoveries which have shaped and morphed into a good global citizen who is able to think righteously, truthfully, kindly, beautifully, and positively about everything is truly wise. This whole beauty package was indeed embbeded within and marked at birth which you are able to unravel it! Thank you for sharing the post which has been a vehicle to beautiful scenery and touching stories!!

Thank you for your kind words Chandra!

Thanks for sharing this Dorje. That type of stigma is tough for anyone to handle much less kids.